Nicole: Thank you for having me and welcome everybody. We are going to talk about sleep in pediatric occupational therapy practice using a family-centered approach. I want to emphasize that this was a group project. I presented this originally at the 2017 AOTA conference with Jason Browning, Tiffany Grace Vasco, Kaylee Gardner, and Nathan Sharba. Jason is currently a Ph.D. student in our program here at Nova, and Tiffany, Kaylee, and Nathan are all graduates of our master's program. They have allowed me to present this with OccupationalTherapy.com, and they are all out there practicing and pushing for increased attention to this area in OT practice. I want to thank them for allowing me to do this.

There is a lot of emphasis on occupation-based approaches, and we will figure out where sleep falls into that designation.

What is Sleep?

From the American Sleep Association standpoint, it is a natural state of both the mind and the body with an altered state of consciousness. Until the 1950s, sleep was thought of as a passive process, but now we know that sleep is actually an active process. It is restorative in nature, and it strongly affects our daily occupations. How are we going to participate in those occupations? How will we be able to perform in them? I am sure most of us can think about when we are tired and how it is easy to put something off because we are too tired to do it. The performance will go down or decrease because we are tired or fatigued. This is true for children as well.

Importance of Sleep

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine declared that sleep deprivation is a public health issue as it is so pervasive at this point. They are sounding the bell that we need to do something about this. Sleep is crucial for a homeostatic balance within the body that we need in order to participate in our daily occupations because they take so much energy, both physically and mentally. When you have a situation where someone has a lack of sleep and it is not treated, the effects can be cumulative. It can lead to greater issues such as potential disease processes (Institute of Medicine, 2006). What I hear from OT's in the community is that they have a lot of families who point this out as a problem or concern. We, as OT's, should be addressing but often we do not know how to go about that. I am hoping by the end of this course that you will feel that you have that ability to do that because we can intervene and make a huge difference.

Sleep is the primary occupation of children until the age of five and often into adulthood (Matricciani et al, 2013). We are so busy looking at self-care, ADLs and play with this age range that often we forget to look at sleep. Again, it is their primary occupation until five so that just shows you how important it is. If it is overlooked, we are really doing something wrong in practice. A few years ago, Sleep in America® (2014) completed a poll of children and found was that children are getting less than the recommended hours of sleep.

There are a lot of reasons why this may occur. One reason is that school starts really early in the morning. For example, early school start times is the number one problem where I live in Fort Lauderdale, and it has to do with the busing. They use the buses to transport to different schools. In rural communities, some of those kids have really long bus rides. If you think about a child with a disability, they take longer to get ready thus they are waking up even earlier. I used to treat a child with spina bifida, and their mom told me they used to wake up at 4:30 in the morning.

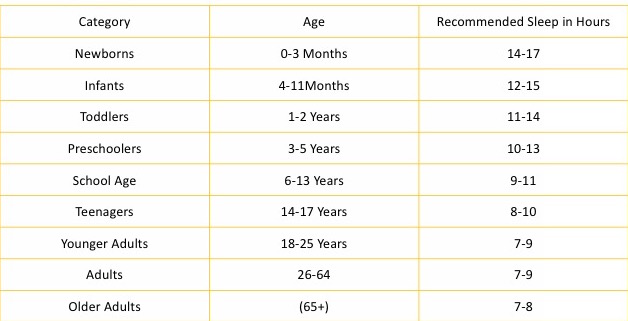

What are these recommendations? These are the recommendations per age (Hirshkowitz, 2015), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sleep recommendations.

If you look at the category of newborns, zero to three months, it is 14 to 17 hours. There is a high amount of variability amongst studies. Another example is that some infants are fine with 12, some are fine with 15. You will start to see that that variability starts to decrease as they get older, especially when they get to be school-age. You see that in that category it is a range of nine to 11 hours, so the variability is two hours difference. Teenagers need 8 to 10 hours, and then in the 18 to 25 year age range, 7 to 9 hours. Once we get into adulthood, seven hours can be enough for some people.

Now, I want you to take a second to think about some of the clients on your caseload and think about how many kids you think are getting the full recommended sleep in hours on a consistent basis. From the discussions, I have had at the AOTA conference and what I have seen in other presentations, the majority of therapists think that clients are not getting the recommended sleep. This has been highlighted as a public health issue because it is pervasive across all populations, all areas of the country, and all age ranges. This includes adults as well.

Sleep: Children and Family

It also impacts the family. Decreasing a child's sleep by just one hour can have a negative influence on emotional functioning, behavior, and cognitive skills that are needed to perform in school (Vriend et al., 2013). That one hour has a pretty significant influence. Another study found that it is estimated between 20 to 30% of the pediatric population has problems with sleep (Mindell, Telofski, Wiegand, & Kurtz, 2009). There are some other problems with sleep as well. When I was a kid, I was a sleepwalker, and that is a type of sleep dysfunction as well. Sleep deprivation and interruption not only affects children but also siblings and caregivers (Byars, Yeonmans-Maldonado & Noll, 2001). These are the kids that wake up throughout the night and have some level of behavioral insomnia. They may come in and climb into dad's mom's bed, up in the middle the night making noise, sleepwalk, or have some bad dreams or night terrors. There could also be bedwetting. Another big area is the back and forth struggle of getting the kids to go to bed at night. So a lot of parents will report there are challenges with getting the children to go to bed so that's another area that can be challenging as well and that will affect the whole family.

Sleep and the OTPF

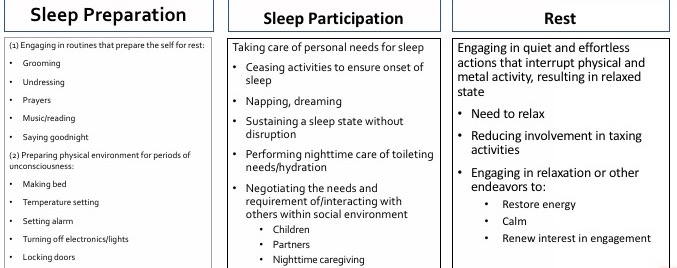

We have taken the areas of sleep from an occupational standpoint and the OTPF (see Figure 2). Sleep is the only occupation in the OTPF that is performed completely independent (Koketsu, 2013).

Figure 2. OTPF and sleep.

There are three categories of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: sleep preparation, sleep participation, and rest. Sleep preparation is where you engage in routines that prepare the self for rest and also preparing the physical environment for periods of unconsciousness. You can see all the things here that are involved with that process: grooming, undressing, prayers, music and reading, and saying goodnight. The physical environment includes making the bed, setting the temperature, setting the alarm, turning off lights, and locking doors. Every night before I go to bed (in Florida), I have to make sure and turn the air conditioning down just a little bit to make sure it is not too hot especially for my dog. Turning off electronics and lights are important things because there are lots of studies about the effects of light (even on electronic devices) and how they disrupt our sleep. You may need to look at lights in other areas like a cable box as well. They can be blacked out or turned away from the bed.

Sleep participation starts with the cessation of activities to ensure the onset of sleep. Napping, dreaming, sustaining sleep state without disruption are other areas, which for some of us can be very hard especially if there are little kids in the home. This is one of the many challenges parents describe when they have a child who has some kind of sleep disturbance. Performing nighttime care of toileting needs and hydration are also included here. Negotiating the nighttime needs and interacting with others within the social environment round out this category. This would be parents dealing with children or dealing with a partner in the nighttime caregiving. Some of our kids that are more are physically involved might have increased nighttime caregiving. They may need to be moved or shifted, for example, if they have a spinal cord injury.

Rest as defined in the OTPF is engaging in quiet and effortless actions that interrupt physical and mental activity that allow for a relaxed state. This involves the need to relax, reducing involvement in taxing activities and engaging in relaxation to restore energy, be calm, and renew interest in engagement. I think this why mindfulness has become so popular. It is forcing us to engage in some kind of rest because we have gotten away from that in our technology-driven and very busy schedule.

Neuroscience of Sleep

What are the components of sleep? REM sleep is the rapid eye movement of sleep. REM sleep is extremely important for memory and visual perceptual learning (Poe, Walsh, Bjorness, 2010). The total time in REM sleep is not as important as the REM sleep that is accomplished during high learning demands. It is not about how long you are in REM sleep, but about the quality of the REM sleep. You need to get into a very deep sleep to have really good REM sleep. Our kids that have disrupted sleep do not necessarily have a good REM sleep. For those of you that have dogs at home, dogs are a great way to look at sleep because dogs know how to sleep. Most dogs can sleep really well as they go in pretty deep. They will be still, but their eyes are moving. Non-rapid eye movement sleep is where your dog will bark or move their legs like running around. It is cyclic between REM and non-REM. We usually go about three or four times through the cycle, and then eventually you will wake up after going through REM sleep. REM is typically where you have your dreams. REM sleep is where the hippocampus in your brain is involved in associative learning and memory consolidation. The hippocampus has a lot of high activity during REM sleep so this is where the hippocampus has a restorative process. The other thing is learning can prolong or intensify REM sleep so the more intense the learning process is, it has an effect on the intensity of REM sleep, and we want to make sure that these kids are getting that intense REM sleep.

Non-REM sleep is often when you wake yourself up because you are moving around. With kids, it can seem you are sleeping with a boxer because they will move around so much. Non-REM sleep is really important for memory interleaving and consolidation, but the thing about non-REM sleep is that it gives your brain a break as well. You will get a nice intense non-REM sleep if you have really been physically active. The more physically active you are, the more intense your non-REM sleep will be.

REM sleep deprivation inhibits the long-term potentiation of your cells and the induction and maintenance. If you deprive your REM sleep, it has negative consequences. Basic cellular excitability metrics are depressed after the REM sleep deprivation. We really want to make sure that kids are getting good REM sleep. They found in the Hairston study in 2010 that after only six hours of REM sleep restriction, you start having consequences with impaired place learning. There are very important things to consider with the ramifications of REM deprivation and REM vs. NREM sleep.

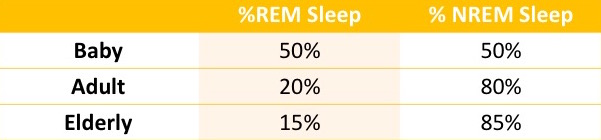

Figure 3. REM vs. NREM sleep.

Figure 3 shows the percentages of REM versus NREM sleep when we start thinking about the age ranges. Babies should be about half-and-half, so half of the time they are in REM sleep and the other half in NREM sleep. As you become an adult, that lessens and you are going to see that the REM sleep is about 20% because you are going more through those cycles with bigger NREM cycles. In the elderly, it is about 15% REM sleep and about 85% NREM sleep. I guess the whole idea is that there is less learning that takes place.

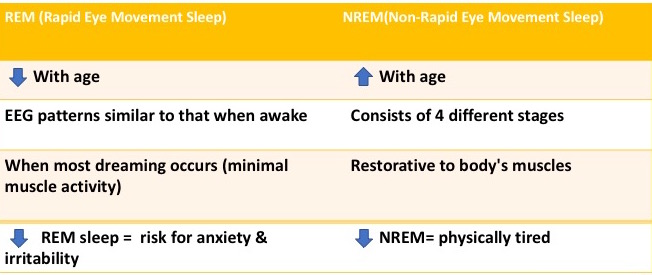

Again, these cycles of REM versus NREM are really important (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Differences between REM and NREM.

In REM, the EEG patterns are similar to that when we are awake, and this is when most dreaming occurs with minimal muscle activity. This is when the body is resting. When you have decreased REM sleep, as stated earlier, there is a huge effect towards learning. There is also a huge risk for anxiety and irritability. Kids are most cranky when they have not had enough REM sleep. This makes sense for learning too. We do not really learn when we are anxious because our limbic system is activated. We cannot really learn when the limbic system is activated because cognitive energy is not really accessible. You are in a state of divided attention. We form memories when we are in sustained attention. Non-REM (NREM) sleep is also very important, as also noted earlier, and it increases with age.

There are four different stages that we go through: non-REM, REM, non-REM, and then REM. It is restorative to the body's muscles as well. You are getting this movement in NREM, but it is restorative to body muscles and you get complaints about being physically tired without it. If the child does not get enough sleep, they will tell you that they are tired. They did not get enough NREM so that usually has to do more with the number of hours, whereas REM is more the quality of the sleep. Reflect on this with your own sleep scenarios. When you are cranky, has your REM sleep been affected? There is a difference between the lack of REM (crankiness) and the lack of NREM (tired).