Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Supporting Regulation As A Foundation For Effective Therapy, presented by Lyn Bennett, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to distinguish the difference between self-regulation and co-regulation.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze 3 components of how sensory processing impacts regulation and dysregulation.

- After this course, participants will be able to evaluate 2 strategies that can be implemented to support regulation during a therapy session.

Introduction

It's a pleasure to be here once more. I'm eager to engage in a discussion about the subject of regulation, a topic that has always held a special place in my professional interests. Regulation serves as a fundamental pillar for achieving effective therapeutic outcomes.

In my role as a DIR Floortime practitioner, I've had the privilege of witnessing firsthand the critical role regulation plays in the therapeutic process. Unfortunately, our time is limited today, and I won't be able to delve into the intricacies of DIR Floortime therapy. However, I would like to briefly reference its significance in the context of regulation.

DIRFloortime

- D - Developmental

- I - Individual Differences

- R - Relationship Based

- Floortime - Intervention

Although some of you may already be well-acquainted with this, it's important to clarify for those who may not be familiar with the terminology. In our context, DIR stands for Developmental, I for Individual differences, and R signifies that it's a Relationship-based approach. These three components form the core of our framework. It's crucial to keep this in mind because, as we progress through the later part of the presentation, we'll be drawing upon these elements when discussing various interventions.

Definition of Terms

- Regulation - alert and available to engage and interact

- Self-regulation - monitor and manage one's own internal states in response to internal and external stimuli

- Co-Regulation - monitor and manage internal states in the context of a relationship with another person

- Emotional regulation - respond effectively to emotional experiences

- Sensory Processing - register, discriminate, categorize, judge, and respond to sensory stimuli

Let's ensure we're all on the same page as we begin our discussion. We'll delve deeper into the concept of regulation shortly, but here are some fundamental definitions:

First, regulation is about being alert and available for engagement and interaction.

Next, self-regulation involves monitoring and managing your internal states in response to both internal and external stimuli.

Co-regulation, on the other hand, means monitoring and managing these states within the context of a relationship with another person.

Emotional regulation relates to responding effectively to emotional experiences.

And sensory processing is essentially how we register, discriminate, categorize, judge, and respond to sensory stimuli.

Many of you are likely familiar with sensory regulation, which entails processing and responding effectively to the sensory inputs we both receive and emit. We'll dive deeper into these concepts as our discussion unfolds, but it's important to have these foundational definitions in mind as we progress.

Stanley Greenspan, MD

- "If your child is going to develop a healthy personality with the capacity to remain intact and grow, she must learn how to test reality, regulate her impulses, stabilize her moods, integrate her feelings and actions, focus her concentration, and plan."

I'd like to take a moment to share some wisdom from Stanley Greenspan, the founder of DIR Floortime. This quote encapsulates the essence of our discussion today. It underscores the vital role of regulation in enabling individuals to connect with and engage effectively with the world around them.

What Does Regulation Look Like?

- Regulation is an internal state and does not look the same externally for everyone.

- Regulation does not necessarily equal being CALM.

- Being well-regulated is when the energy matches what’s needed for various activities.

- Playing a sport may require being upregulated.

- Studying in a library may require being downregulated.

- Eye contact is not an indicator of being regulated, and requiring this can be very dysregulating.

Now, let's explore what regulation actually looks like. We're often taught that being regulated means being calm and alert, which is undoubtedly one aspect of it, but it's crucial to understand that it doesn't manifest the same way for everyone. Think of it as an internal state.

What we observe on the outside may not always reflect the internal state. So, it's challenging to judge someone's regulation solely by their outward appearance. Essentially, being well-regulated means that your energy level matches the demands of the situation you're in. For instance, if you're engaged in a high-energy activity like playing a sport or attending a rock concert, you may be upregulated, displaying high energy. This will look quite different from someone who is calmly studying in a library or taking an exam. However, in both scenarios, you can still be regulated, despite the outward differences.

It's essential to dispel the notion that regulation is solely about sitting still and appearing very calm. It can manifest in various ways. Also, remember that eye contact is not a reliable indicator of regulation. For some individuals, requiring eye contact can be dysregulating, especially if they find it challenging. It is important to avoid using eye contact as a measure of someone's regulation.

Now, when considering regulation, think about the depth or band of regulation. This concept applies to individuals of all ages, although I often discuss it in the context of children, given my background. Essentially, what we're interested in is understanding a person's capacity to shift between different levels of regulation – going up when needed and coming down when necessary. It's about flexibility in their regulatory states.

Bands of Regulation for the Same Sensory Input

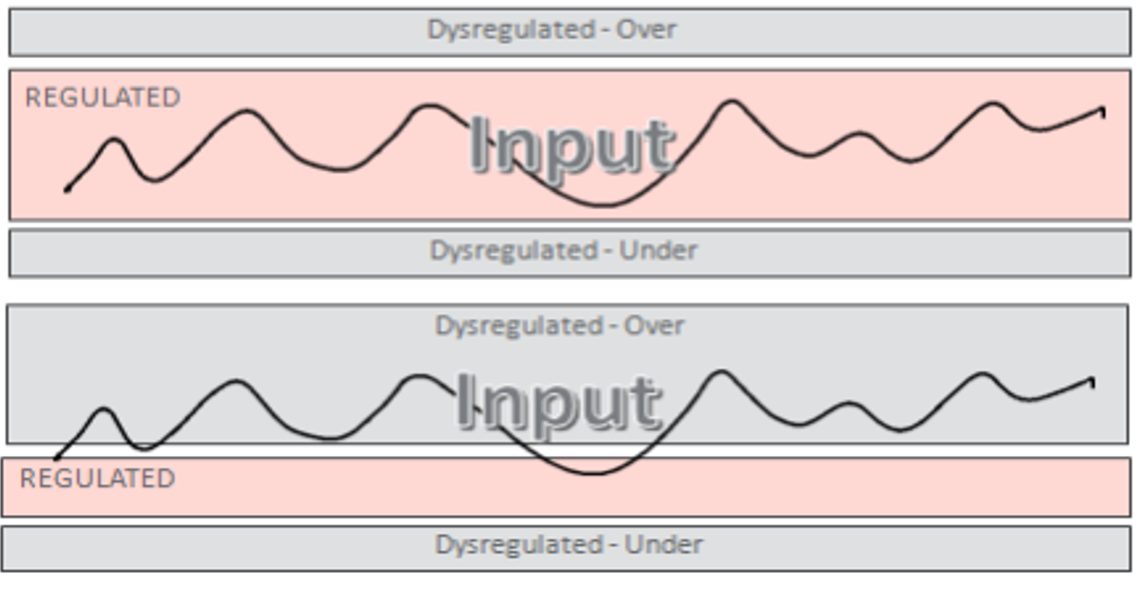

Everyone has a band of regulation where we might go up and down in our alertness throughout the day. However, we stay within the state where we are regulated. Figure 1 shows an example of this.

Figure 1. Bands of regulation.

Regulation varies from person to person, with not everyone possessing the same depth or band of regulation. Some individuals can handle a substantial amount of sensory input while remaining regulated, while others may require much less stimulation to stay within their regulation band. This concept is a crucial consideration when working with our clients.

I'd like to illustrate this with a couple of diagrams. In the top graph, you can see an individual with a reasonably sized band of regulation (pink area). The wiggly line represents the amount of sensory input they are experiencing. Imagine this as a child in a classroom where there are varying levels of activity and stimuli. Despite the fluctuations in input, this child consistently stays within their regulated band.

Now, in the bottom graph, we have a different individual with a much smaller band of regulation. They are exposed to the same sensory input as the previous child, but they struggle to stay within their regulated state. They start near regulation but quickly shift into an overregulated or dysregulated state (gray area). Occasionally, they might briefly dip into regulation, perhaps during nap time, but the majority of the time, they find it challenging.

What's worth noting, especially for the child in the top graph, is the buildup at the end of the day. This is when parents often encounter difficulties. They pick up their child and offer a snack or juice, and the child suddenly reacts negatively. It might seem to be an extreme reaction over a minor issue, like the wrong flavor or color. This is where it's essential to consider how much effort the child puts into staying regulated throughout the day. The end-of-day meltdowns may not be directly linked to the triggering incident but rather to the accumulated strain from maintaining regulation all day.

As therapists, our role is to probe beneath the surface to understand what's driving these reactions. It's not about fixing the specifics of the situation, such as the flavor of the juice or the color of the wrapper. Instead, it's about comprehending what's happening underneath and what led to this response. Our goal is to support the child in addressing the underlying factors rather than the immediate trigger.

Regulation?

I'd like to share a brief video featuring a young boy I worked with several years ago in a school setting. This child had an extremely narrow band of regulation, often oscillating between complete self-absorption and intense screaming in his preschool classroom. At the time, I was seeing him for occupational therapy, and I was in the midst of my DIR training, which required frequent video documentation of my interactions with children.

As I was setting up the camera, I captured a 30-second snippet of his behavior, which appeared to encapsulate the challenges he faced daily. Let's take a moment to watch this video to better understand his experiences.

Video

From that video, it's quite evident that this young boy's behavior oscillated between states of inactivity and intense screaming. This pattern seemed to be a significant part of his daily experience. Our goal in working with him was to identify those precious moments in between these extremes. By capturing those moments of relative calm and regulation, we aimed to help him expand his band of regulation. This way, he could have more periods in his day when he felt comfortable, engaged, and able to participate in his surroundings.

What Does Dysregulation Look Like?

- Dysregulation can present with an over-responsive or an under-responsive pattern.

- Over responsive examples:

- Crying, screaming

- Throwing the body to the floor

- Hitting, kicking

- Running away

- Under responsive examples:

- Withdrawn

- Not responding to sensory stimuli

- Not engaging with anything or anyone

- Absorbed in one thing

Recognizing dysregulation is crucial in our work, and it can manifest in a variety of ways. It's important to note that this list is not exhaustive, but it provides some insights into what we might encounter. Dysregulation can present as either an over-responsive or an under-responsive pattern.

Over-responsive dysregulation often involves behaviors like crying, screaming, throwing oneself to the floor, hitting, kicking, or running away. It's marked by an exaggerated reaction to sensory stimuli.

On the other hand, under-responsive dysregulation may be characterized by withdrawal. Individuals in this state may not respond to sensory stimuli, fail to engage with people or their surroundings, and become intensely absorbed in one thing while blocking out everything else.

As occupational therapists, our aim is to prevent dysregulation from reaching these extreme points. Our focus today is not on how to manage these states but rather on how to recognize when dysregulation is beginning to occur, so we can intervene before it escalates. Dealing with someone in such a deeply dysregulated state often requires simply helping them regain regulation.

Additionally, it's worth noting that a bit of challenge is essential in our role as therapists. We don't aim to keep individuals in a constant state of calm; rather, we want to help them navigate different experiences and emotions. The key is to strike the right balance, offering challenges while being vigilant to recognize when stress or dysregulation is emerging.

Factors Influencing Regulation

- Sensory processing

- Praxis

- Communication

- Health

- Sleep/tiredness

- Hunger

- Experience of the day

- Relationships and support systems

- Trauma

- Attachment

Today, we are focusing on the sensory aspect of regulation, but it's important to recognize that regulation is influenced by a multitude of factors. These elements can significantly impact an individual's capacity to stay regulated.

Communication plays a significant role in regulation. Understanding how a child communicates and their capacity to express themselves is essential. Communication isn't limited to language; non-verbal cues are just as vital.

The physical well-being of a child is a fundamental determinant of regulation. Factors such as sleep, tiredness, and hunger can profoundly affect their ability to stay regulated.

Assessing what a child has experienced throughout the day is vital. Whether they've been exposed to increasing sensory input or have enjoyed a calming and relaxing day at the park can significantly impact their regulation.

Within the broader context, understanding the child's life in terms of relationships and support systems is important. On a daily basis, consider the immediate influences on the child. Have they been around supportive individuals who have helped them navigate challenges, or have they faced a more stressful environment?

Both trauma and attachment issues are monumental components in regulation. It's crucial to remember that sensory processing issues in a child might be closely linked to trauma or attachment rather than sensory processing alone. When assessing and providing therapy, it's essential to be mindful of these aspects. Trauma can be triggered by certain sensory stimuli or activities in therapy, making it a critical consideration in our work.

In conclusion, understanding and addressing these various factors is key to helping individuals achieve and maintain regulation. For occupational therapists, it's highly recommended to pursue further education in trauma and attachment, as these are substantial components of the challenges we face in our profession.

Sensory Experience and Emotion

Sensory experiences have an emotional response.

AND

Emotional experiences have a sensory response.

- By integrating and managing these experiences, we develop self and emotional regulation.

- It is important to be able to regulate through a wide range of emotions.

- Coregulation in the context of a relationship is essential in early life and continues to be a component of regulation throughout life.

It's crucial to understand that sensory experiences and emotions are intricately interconnected. Whenever we encounter a sensory stimulus, it triggers an emotional response. These emotional responses can vary in intensity, and we may perceive sensory input as pleasurable, painful, or anxiety-provoking. Conversely, emotional experiences also evoke sensory responses in our bodies. For example, when we feel anxious, we might experience bodily sensations unique to each of us.

It's fascinating how individual responses to these experiences can be influenced by early life events. For instance, my older son used to complain of throat pain when he was stressed, which made me wonder if it related to his birth experience, as he was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck multiple times, possibly giving him a sense of being strangled.

Developing emotional regulation is all about integrating and managing these sensory-emotional experiences. It's about learning to manage our emotional responses to what we're experiencing. Emotional regulation isn't limited to just "positive" emotions – it encompasses the ability to navigate the full spectrum of emotions, including stress and sadness.

Co-regulation, which occurs in the context of a relationship, is a critical component in the development of self-regulation. Right from infancy, caregivers help babies learn to regulate their emotions. Babies aren't left to cope with their feelings on their own; they are held, soothed, changed, and fed, and these sensory experiences are coupled with emotional expressions and tone of voice. This co-regulation assists the child in gradually learning how to manage some of those emotions independently.

In essence, co-regulation is a fundamental building block in developing self-regulation.

Coregulation Video

This is a video that we were not able to share directly in class, but I would love for you to watch it after class. This is also available in your handout. This is a great example of coregulation between dad and baby, highlighting a powerful and unconscious bonding experience.

Moving on, let's delve into the sensory processing aspect. We'll explore each of the eight sensory systems briefly, considering both over-responsiveness and under-responsiveness. This list is not exhaustive but offers some examples for each system. As we discuss these systems, it's essential to think about how we can monitor and address over and under-responsiveness within each one. Moreover, we should identify which sensory systems pose challenges for the child and which ones can be leveraged to support their regulation.

Eight Sensory Systems

Vestibular Processing

- Over responsive:

- Easily becomes dizzy or nauseous when using movement equipment

- Avoids movement activities

- Anxious when swinging

- Prefers sedentary play

- Under responsive:

- Poor balance and poor posture

- Clumsy, poor bilateral coordination

- Runs, spins, climbs

- Loves to swing fast and high

Let's take a quick look at the sensory systems, starting with vestibular processing. In terms of over-responsiveness to vestibular input, we may observe a child who easily becomes dizzy or even nauseous when exposed to movement activities. They might avoid such activities and express anxiety when swinging or engaging in any form of movement. They tend to prefer sedentary play, perceiving it as safer.

On the other hand, a child who is under-responsive to vestibular input may exhibit poor balance and posture. They might appear clumsy, struggle with bilateral coordination, and seek excessive sensory input. These are the kids who enjoy running, spinning, jumping, and love to swing fast and high.

Proprioceptive Processing

- Over responsive:

- Anxious about weight bearing and movement activities

- Lacks confidence in new motor activities and sports

- Doesn’t like hugs

- Under responsive:

- Seeks input - jumping, pushing, pulling

- Need to watch their own movements

- Difficulty modulating force of movement

Now, let's consider the proprioceptive system. For those who are over-responsive to proprioceptive input, they may feel anxious about weight-bearing and various movement activities. These individuals might lack confidence when attempting new motor activities, and they could be uncomfortable with physical contact like hugs.

Conversely, someone with an under-responsive proprioceptive system might actively seek input by engaging in activities like jumping, pushing, or pulling. An under-responsive system means they may need to visually monitor their movements since they don't adequately sense the feedback. Additionally, individuals with this profile often struggle with modulating the force of their movements, leading to either excessive or inadequate force application.

Tactile Processing

- Over responsive:

- Dislikes or avoids certain textures, messy play

- Only tolerates some items of clothing

- Avoids explorative play

- Anxious about others touching or standing close to them

- Under responsive:

- Difficulty identifying/differentiating by touch alone

- Not aware of messy hands or face

- Seeks input by touching objects and people

- High tolerance for pain

Moving on to tactile processing, when someone is over-responsive, they may exhibit aversion to or avoidance of specific textures. They are likely to dislike messy play and might have a limited tolerance for certain clothing materials. These individuals often avoid explorative play, as it can be overwhelming and anxiety-inducing. Moreover, they may feel anxious about others touching them or standing too close, which can lead to behaviors like avoiding standing in lines or crowded situations.

On the other hand, those who are under-responsive to tactile input may struggle to identify objects solely by touch and may rely on their visual system for support. They may not be aware of getting messy on their hands, face, or body. Seeking behaviors are common, such as touching objects or people to gain a sense of where their body ends. Additionally, individuals with an under-responsive tactile system may exhibit a high pain tolerance, which can be a safety concern.

Visual Processing

- Over responsive:

- Startled by sudden or unexpected movements

- Avoids bright lights

- Overwhelmed in visually busy environments

- Covers eyes, squints

- Under responsive:

- Walks or bumps into things

- Watches objects spin/move, flickering lights

- Looks at objects close up or from the corner of the eye

- Moves head when reading or writing

In terms of visual processing, individuals who are over-responsive may be startled by sudden or unexpected movements. They might avoid bright lights and feel overwhelmed in visually busy environments. These individuals may often cover their eyes or squint in response to sensory overload caused by visual input.

On the other hand, someone who is under-responsive to visual input may exhibit behaviors like walking into objects or bumping into things as they seek more input. They might find enjoyment in watching things spin or move and could be attracted to flickering lights. Additionally, they may prefer looking at objects from the corner of their eye or very close up and may move their head while reading or writing to enhance their sensory experience.

Auditory Processing

- Over responsive:

- Dislikes or is scared by loud sounds

- React to or distracted by background sounds

- Overwhelmed in noisy environments

- Doesn’t respond to instructions

- Under responsive:

- Unaware of environmental sounds

- Doesn’t respond when spoken to

- Difficulty modulating the volume of the voice

- Make sounds such as humming

Regarding auditory processing, someone who is over-responsive may exhibit a strong dislike for or fear of loud sounds. They might react strongly to background noise and become easily overwhelmed in noisy environments. This sensory profile can lead to difficulties in following instructions, not because they can't hear them but because they are so distracted by the surrounding auditory stimuli. This can be especially challenging in classroom settings when external noises disrupt their ability to focus on the teacher.

Conversely, individuals who are under-responsive to auditory input may not be fully aware of environmental sounds, which can be a safety concern. They may not respond when spoken to, struggle to modulate the volume of their voice, and often speak loudly without realizing it. These individuals may also make sounds, such as humming, as a way to hear themselves, compensating for the lack of internal feedback in their auditory system.

Gustatory and Olfactory Processing

- Over responsive:

- Very aware of smells, e.g. perfumes

- Avoids settings due to smell, e.g. bathroom, restaurants

- Limited diet, avoids strong tastes and smells

- Gags in response to certain flavors or aromas

- Under responsive:

- Difficulty identifying tastes or smells

- Seeks/enjoys strong tastes and smells

- Smell or lick non-food items, including people

Gustatory and olfactory processing are closely related sensory systems. When someone is over-responsive in this area, they are highly aware of smells, including perfumes. As a result, they may avoid certain settings due to overwhelming smells, such as bathrooms or restaurants. Over-responsive individuals may have a limited diet and tend to avoid strong tastes and smells. Certain flavors or aromas might trigger gagging or even vomiting in their response.

Conversely, individuals who are under-responsive to gustatory and olfactory input may have difficulty identifying different tastes or smells, which can pose safety concerns. They may seek out or enjoy very strong tastes and smells, and they might engage in sensory-seeking behaviors like smelling or licking non-food items, which can sometimes include people.

Interoceptive Processing

- Over responsive:

- Very aware of and distracted by internal sensations

- Anxious in response to feelings of hunger, thirst, need to use the bathroom, temperature change, sound of own heartbeat

- Under responsive:

- Difficulty interpreting the meaning of internal sensations

- Not aware of hunger, thirst, need to use the bathroom

- Not aware of the body becoming tired, cold, overheated

- Lacking awareness of pain

Lastly, we have the interoceptive system, which pertains to one's awareness of internal bodily sensations. Over-responsive individuals may be highly tuned in to and easily distracted by internal sensations, even simple movements inside their stomach, for instance. They may become anxious in response to feelings of hunger, thirst, the need to use the bathroom, temperature changes, or even the sound of their own heartbeat. These heightened sensitivities can lead to a preoccupation with internal sensations, causing them to miss out on other external stimuli.

Conversely, those who are under-responsive to the interoceptive system may have difficulty interpreting the meaning of internal sensations. They might sense something happening in their body but struggle to identify what it signifies, or they may not be aware of these sensations at all. This can create safety concerns, especially in extreme weather conditions or when it comes to toilet training, as they may not perceive when they need to use the bathroom. Additionally, they might lack awareness of being tired, cold, overheated, or even experiencing pain, which can be problematic.

Developing and Maintaining Regulation

- Support child’s regulation prior to starting any activities

- Constantly observe the child for early signs of dysregulation

- Use the “just right challenge” to stretch the child’s capacity to regulate through sensory and emotional experiences

- If the child does become dysregulated, how long does it take for them to recover?

When considering the various sensory processing systems and their impact on regulation, it's essential to recognize the emotional component intertwined with these sensory experiences. Many of the signs and challenges associated with different sensory profiles, as we discussed earlier, are closely linked to emotions. Anxiety and fear often accompany sensory sensitivities, whether it's hypersensitivity to tactile sensations, over-responsiveness to loud sounds, or a heightened awareness of internal bodily sensations.

Emotions play a significant role in an individual's ability to regulate themselves in response to sensory input. For instance, someone who is hypersensitive to tactile input may experience anxiety or fear when confronted with certain textures or sensations. This emotional response can lead to avoidance behaviors and a reluctance to engage in activities that involve those sensory triggers. Similarly, over-responsiveness to auditory stimuli can evoke fear or anxiety in noisy environments, making it challenging for the individual to concentrate or engage effectively.

Another crucial consideration is safety. Safety concerns are prevalent, whether an individual is under-responsive or over-responsive to sensory input. Under-responsive individuals might struggle to perceive when they are in discomfort, hungry, or experiencing temperature changes, which can pose safety risks. Conversely, over-responsive individuals might engage in risk-taking behaviors to seek sensory input, potentially compromising their safety.

In any therapeutic setting, whether it's a therapy session or another form of intervention, ensuring that the child or individual is regulated is paramount. Without regulation, full engagement and participation are compromised, hindering the effectiveness of the therapeutic experience. Therefore, the initial focus should always be on establishing and maintaining regulation. It's crucial to invest the necessary time in helping the individual achieve a regulated state, as this sets the foundation for a productive therapeutic interaction.

However, regulation is not a one-time achievement that signals the start of therapy. It's an ongoing process throughout the therapeutic session. Being regulated at the outset is essential, but it's equally important to sustain that regulation as the session progresses. This ensures that the individual can fully benefit from the therapeutic experience and achieve the best possible outcomes. Therefore, regulation is not just a box to check at the beginning; it's a continuous, dynamic aspect of the therapeutic journey that must be nurtured and maintained.

Early Signs of Dysregulation

- Change in activity level

- Increase in sensory seeking

- Increase in sensory avoidance

- Change in facial expression

- Change in breathing

- Change in communication - talking more or becoming silent

- Turning body away, leaning back

- Yawning

- “Negative” self-talk - I can’t, it’s too hard

In the context of therapy or any therapeutic interaction, the key is to be vigilant and attuned to the child's regulatory state throughout the session. It's an ongoing process of observation and adjustment to ensure the child remains within the band of regulation. This entails a delicate balance between providing a "just right challenge" and not pushing the child into a state of dysregulation.

The "just right challenge" is the sweet spot where the child is being stretched just enough to promote their developmental growth without overwhelming them. It's a delicate balance that requires therapists to continuously adapt their approach based on the child's responses. The goal is to help the child learn to regulate themselves through the sensory and emotional experiences they encounter during therapy. If therapy were solely about keeping the child happy and comfortable, it wouldn't facilitate their growth and development effectively.

However, it's essential to monitor the child's responses closely. Dysregulation can occur in various ways, and therapists need to be attuned to these signs. One key indicator of dysregulation is a change in the child's activity level. This could involve restlessness, excessive fidgeting, or, conversely, a loss of engagement and participation, leading to more sedentary behaviors.

Children may also display sensory-seeking behaviors as a means to self-soothe and regulate. This could manifest as a need for tactile input or other sensory experiences to help them cope with stress. On the flip side, they may begin to avoid certain activities or stimuli, signaling their inability to cope with the sensory or emotional demands.

Observing changes in facial expressions, breathing patterns, and communication is crucial. Children may show signs of discomfort or distress through shifts in their facial expressions and may even begin self-talk that reflects their struggle, such as expressing frustration or a lack of confidence in their abilities. Changes in body posture, like turning away or leaning back, can also signal dysregulation. Additionally, yawning is a subtle yet telling sign that a child is starting to struggle with regulation.

By being attuned to these signs and responses, therapists can make real-time adjustments to the therapy session to support the child's regulation and ultimately help them achieve the therapeutic goals effectively. The key is not to push the child into dysregulation but to provide the right level of challenge that promotes growth while ensuring the child remains within their regulatory band. Progress can be observed in how quickly the child recovers from dysregulation episodes, signaling their increasing capacity for self-regulation over time.

Video: Regulating Through Vestibular Anxiety

In the video, we observe a young boy during a therapy session where vestibular processing is being addressed. The therapist, alongside the boy's mother, introduces a new swing that the child has not encountered before. The focus is on developing the child's vestibular processing, but there's a keen awareness of his potential for rapid dysregulation.

As we watch the video, we can discern several signs that indicate the boy may be on the verge of becoming dysregulated. These signs include physical tension, as the child appears rigid and may hold his body in a stiff posture, suggesting discomfort or stress. His facial expressions change throughout the session, displaying concern, uncertainty, or mild distress, hinting at sensory overload or discomfort. Paying attention to the boy's breathing patterns reveals irregular or shallow breathing, indicative of stress or dysregulation. In some instances, he might hold his breath briefly, a common response to sensory stress. Listen for any verbal cues from the child, such as expressing fear or uncertainty. Beyond words, children often communicate through non-verbal cues like fidgeting, increased use of gestures, or avoidance behaviors, signaling growing discomfort. The boy may exhibit behaviors like holding onto the therapist or his mother more tightly and seeking physical contact as a form of comfort when experiencing sensory stress. Observe how the child's level of engagement changes throughout the session. A decrease in engagement, such as disinterest or withdrawal, can indicate that he's struggling with the sensory experience. Some children may engage in self-talk, muttering to themselves to cope with sensory stress, which can manifest as verbal expressions of unease or uncertainty.

The primary objective of monitoring these signs during therapy is to ensure that the child remains within their regulatory zone. The therapist and mother work together to provide the appropriate level of support and comfort to help the child manage potential dysregulation. Additionally, it's essential to keep the therapeutic environment safe and conducive to the child's developmental progress, allowing them to explore and adapt to new sensory experiences while staying regulated.

During this session, we observed several subtle signs that indicated the little boy was approaching a state of dysregulation. These signs were important to recognize, as responding to them inappropriately could have easily led to full dysregulation.

One of the noticeable behaviors was the boy engaging in a lot of jumping. This indicated that the proprioceptive system played a significant role in his self-regulation. To cater to this need, the therapist positioned the trampoline near the swing, allowing the child to seek proprioceptive input when he found the swing experience challenging.

The child displayed a pattern of approach and avoidance, where he would approach the swing, feel overwhelmed, and then move away. This fluctuation between curiosity and retreat showcased his struggle to manage the sensory stress. At times, he turned his body away from the swing or looked in different directions, signaling his need to create physical or visual space from the source of stress.

Vocalizations also provided clues to his emotional state. The child frequently made sounds like "whoa" when feeling anxious about the situation. His facial expressions revealed changes, reflecting his varying levels of comfort or distress.

One crucial aspect of the therapeutic approach was maintaining an anchor presence for the child. The therapist and the boy's mother ensured they didn't chase him around, prioritizing safety. This approach allowed the child the freedom to move away, regroup, and return when he felt ready. They rarely called him back directly, instead using indirect invitations to provide a more relaxed and less demanding environment. Imposing demands or expectations might have overwhelmed him.

Additionally, it was fascinating to observe how certain sensory systems were regulating for the child. Proprioception and the auditory system were his sources of comfort. The child had always shown an affinity for music and sound play. When the therapist softly began to sing, the boy's response was almost immediate. He stopped moving, his breathing slowed, and he engaged more directly, even smiling. This highlighted the importance of working on challenging systems while using supportive ones to assist the child's self-regulation.

Crucially, the therapy session didn't push too hard. Placing the child in the swing forcefully could have deterred him from trying it again. However, by allowing him the space to explore, self-regulate, and experience success at his own pace, he left the session with a positive feeling, ready to try the swing again in the future.

Understanding the child's regulatory cues and providing the right balance of challenge and support is crucial in creating a successful therapeutic environment. It's about recognizing the signs of approaching dysregulation and responding appropriately to ensure that the child remains within their regulatory zone, allowing them to grow and adapt to new sensory experiences.

In the midst of the therapeutic session, we made a conscious effort to act as anchors rather than chasing the child around. Safety remained paramount, but we allowed the boy to explore, move away, and regroup on his terms, creating a supportive and non-coercive environment. We rarely insisted that he come back to the swing directly. Instead, we used indirect, less demanding invitations to encourage him to participate.

An intriguing observation was the child's strong regulatory response to certain sensory systems. While we knew that the proprioceptive system was essential for his self-regulation, it was equally apparent that the auditory system played a significant role in calming him. This boy had always exhibited a deep affection for music, sound play, and the exploration of sounds. As a testament to this, when I began singing softly during the session, his response was almost instantaneous.

He stopped moving, sat down, and even maintained steady breathing. He started focusing on the therapist, looking directly at her. This engagement with the auditory stimulation even led to moments of genuine delight and smiling. The therapist noted that they didn't enforce this reaction but were pleasantly surprised by how comfortable he felt in that moment.

This scenario serves as a prime example of the therapeutic approach. It underscored the importance of addressing the systems that pose challenges while capitalizing on those that provide comfort and support. The key was to avoid pushing too hard, recognizing that a forceful intervention could have discouraged the child from attempting the swing again. By granting him the autonomy to explore and self-regulate at his own pace, the session concluded with a sense of accomplishment and the confidence to try the swing again in the future.

In summary, the therapy session demonstrated the significance of recognizing the child's regulatory cues and responding appropriately to create a therapeutic environment that strikes the right balance between challenge and support. It's about understanding when to engage, when to step back, and when to utilize the regulatory strengths of the child to foster a positive and successful experience.

Identifying the Triggers

- D - Is my expectation or the challenge of the activity at the right developmental level for the child in the moment?

- I - What’s happening with the child’s sensory system?

- R - How is the child experiencing my affect and interaction style? How’s my own regulation?

Developmental factors (D) is crucial when assessing the developmental readiness of a child for specific challenges or expectations. Consider whether the activity or therapeutic approach aligns with the child's developmental stage and abilities. It's important to ensure that the challenges presented are neither too advanced nor too simplistic for the child in their current developmental phase. Failure to address this can lead to frustration and dysregulation, as the child may feel overwhelmed or disengaged due to an inappropriate developmental match.

The sensory system plays a pivotal role in regulating a child's responses and emotions. Thus, understanding the intricacies of a child's sensory processing is key. This involves recognizing how each sensory system functions and its particular quirks in the child's case. Sensory awareness can manifest differently from one individual to another, and it's vital to identify the sensory sensitivities or preferences of each child. By doing so, you can tailor your therapy sessions to accommodate or challenge their sensory needs appropriately.

The third component, regulatory influence, involves examining your role and interaction style in the therapy setting. Consider how your presence and affect may affect the child's regulation. For instance, are you providing a sense of safety and emotional stability? Are you fostering a positive and engaging atmosphere? Additionally, self-awareness is key. Recognize your own regulatory state and how it might impact the therapy session. There are days when you may find that everyone around you seems to struggle or become dysregulated, and it's often a valuable realization that the common denominator is your own regulation. Therefore, consistently monitoring your own state of regulation is essential to offer the best support to the child.

DIR offers a comprehensive framework for assessing and addressing triggers of impending dysregulation in therapy. It calls for a deep understanding of the child's developmental stage, their sensory processing, and the impact of your own regulatory influence. By taking these aspects into account, therapists can create a more responsive and effective therapeutic environment that meets the child's unique needs and promotes regulation.

Interventions to Support Regulation - D

- Understand the child’s developmental capacity, not just overall, but in that moment

- Adjust your expectations to meet their current status

- Think “activity analysis” - how can you break down what you are doing into more manageable steps?

- Identify and provide modifications and support for the child to feel successful

- Remember, process over product

In the context of understanding a child's developmental capacity, it is crucial to consider their abilities at a given moment rather than relying on their overall capabilities. While we may have a good grasp of what a child can typically achieve or tolerate, each day can bring unique challenges. Thus, our approach should be tailored to their immediate state, not their best performance.

When evaluating a child's readiness and capabilities, it is vital to factor in elements that can influence their regulation. This holistic assessment includes aspects like sleep patterns, nutritional status, or emotional well-being. Understanding these variables helps us set realistic expectations based on the child's current situation.

Moreover, we employ activity analysis and task breakdown to ascertain the child's readiness and determine the appropriate level of challenge. If a particular task seems too daunting for the child, we aim to deconstruct it into more manageable components. This approach allows us to pinpoint areas where the child might require support or modifications to ensure they experience a sense of accomplishment.

It's important to highlight that our role is not to complete tasks for the child. Offering immediate assistance when we see them struggling does not contribute to their growth. Instead, we should engage them in the process and encourage problem-solving. By jointly addressing the challenges, the child gains confidence and a deeper understanding of their abilities. This approach can be challenging for occupational therapists who are typically oriented toward taking action and achieving results. Nevertheless, it is imperative to emphasize the child's journey of development and the small steps they take. This emphasis on the process, as opposed to the final product, is a fundamental principle in promoting the child's growth. Ultimately, breaking tasks down, guiding them through each step, and fostering their sense of accomplishment are the keys to helping them reach their full potential.

Interventions to Support Regulation - I

- Be aware of factors that could be influencing the child’s regulatory capacity

- Understand the child’s sensory profile

- Consider which systems tend to be dysregulating for the child

- Adapt the environment to reduce stressors

- Consider which systems support regulation

- Make use of the child's areas of strength to support their areas of challenge.

- Be trauma-informed; a child who has experienced trauma or has attachment issues may be triggered by aspects of your intervention.

When delving into the "I" component, we should maintain a keen awareness of the various factors that could influence a child's capacity for regulation. To do this effectively, we must gather information about the child's daily experiences. Understanding their sensory profile is vital: we need to identify their strengths and challenges and determine what elements may potentially trigger dysregulation.

By grasping the aspects that could be causing stress or discomfort, we can then implement modifications to minimize these sources of distress. Furthermore, we should consider which sensory systems can be harnessed to support the child's regulation. It's essential to tailor our approach to leverage systems that align with their sensory processing abilities. For instance, the case of the little boy on the swing underscores how the proprioceptive and auditory systems were harnessed to facilitate his regulation.

A significant aspect of this process is to integrate trauma-informed care. Children who have experienced trauma or have attachment-related issues may exhibit heightened sensitivity to elements of our intervention. Recognizing this, we should exercise extreme care and mindfulness to prevent unintentionally triggering any adverse reactions or emotional distress. This involves creating a safe and supportive environment in which the child's needs are prioritized, helping them regain their sense of control and security.

Video: Ball Pit

In this brief video, let's focus on the young boy with cochlear implants as he is introduced to a ball pit. Several key observations can be made about his regulation and what aids in his regulation.

Initially, it's noticeable that the child simply stands in the ball pit, which is somewhat unusual for a child his age. This behavior suggests that he might be experiencing some level of confusion or being overwhelmed. His sensory processing challenges, particularly related to praxis and vestibular functions, might be contributing to his uncertainty.

The Occupational Therapist (OT) working with him, Carol, employs a noteworthy strategy to help him become more regulated. She begins by using a higher-pitched voice, but it doesn't seem to have a significant impact on the child. Given his cochlear implants, which indicate potential auditory sensitivities, it's important to consider that auditory input may not be his primary strength. However, when Carol lowers her tone of voice, the child becomes more responsive and alert.

Another step in promoting his regulation is when the speaker in the video, presumably another therapist, enters the ball pit and assists the child in lowering himself to a seated position. This change in posture appears to make the child feel safer, as the standing position might have been disorienting and anxiety-inducing for him due to his vestibular challenges.

As he sits down, he begins engaging more with his environment, playing with the balls in the pit, which offers tactile and proprioceptive sensory input. Moreover, the therapists reduce their use of language during this interaction, ensuring that it is not overly stimulating, which further helps the child become more comfortable and engaged.

This video highlights the importance of tailoring sensory input and interactions to a child's specific sensory processing needs, especially when addressing sensory sensitivities and potential sensory challenges. By carefully adjusting these factors, therapists and caregivers can assist children like this boy in achieving a state of regulation and participation.

Interventions to Support Regulation - R

- Be aware of your own individual profile

- Adapt your interaction style to fit what the child needs

- Be aware of what regulates and dysregulates you

- Take care of your regulatory needs before, during, and after your therapy sessions

- Consider what emotions are challenging for you

- Try not to judge emotions as positive or negative

- Allow yourself to pause before responding

- Be authentic in your interactions

When considering the "R" piece, which relates to the relationship aspect of our interactions with children, we must cultivate self-awareness about our own unique profiles. This awareness extends beyond simply understanding our own regulation, although that is undeniably pivotal. It encompasses acknowledging our personal communication styles, energy levels, and behavioral tendencies.

We should reflect on our own traits, such as whether we tend to be soft-spoken or loud, if we naturally make expansive gestures, or if we typically present a more subdued affect. These characteristics significantly influence how a child perceives and responds to us. For instance, a child who is hypersensitive to visual cues may find an exuberant, high-energy adult overwhelming, while another child who seeks such stimulation might not engage with a quieter, more reserved adult. The goal is to adapt our approach to meet the specific needs of the child in achieving regulation, without compromising our authenticity.

Furthermore, it is essential to recognize what supports our own regulation and what might disrupt it. Whether as professionals or parents, we must be aware that if we are not regulated ourselves, assisting a child in attaining regulation becomes a formidable challenge. Therefore, practicing self-care before, during, and after interactions is paramount.

Identifying our own emotional triggers is another critical component. Instead of labeling emotions as positive or negative, it is crucial to view them in a neutral light. We should resist the urge to "fix" a child's emotions. For example, if we find it difficult to tolerate a child's sadness, attempting to make them laugh may not be the most helpful approach. We should allow the child to fully experience and explore their emotions.

Taking a moment to pause before responding is a valuable practice. Frequently, we are inclined to react immediately, but giving ourselves a brief pause allows the child to express themselves and enables us to observe their cues. Authenticity in our interactions is paramount because children are astute at discerning whether we are trying to convey emotions that do not genuinely align with our feelings. Being authentic is crucial in establishing trust and building meaningful connections with children.

AGILE - Gerard Costa, 2022

In conclusion, I would like to draw your attention to a valuable article that I have made available for download. This resource has proven to be incredibly beneficial for my students in the DIR Floortime model when they are considering regulation and managing their therapeutic interventions. The article is based on the acronym AGILE, which stands for:

A - Affect and emotional state.

G - Gestures, expressions, movements, and body posture.

I - Intonation.

L - Latency, which refers to pacing.

E - Engagement.

In the Floortime model, we emphasize the practice of "wait, watch, and wonder," which has proven to be powerful. It involves waiting for the child's cues, observing their actions, and wondering about their intentions and feelings.

Today, our focus has primarily been on the first developmental level, which is regulation. I've managed to stay within our allotted time, but I'm more than willing to address any questions or engage in discussions for a few additional minutes if there are any inquiries.

Questions and Answers

Any tips on getting buy-in for the teachers in the schools?

Building buy-in from teachers in schools is a common challenge. I recommend taking an incremental approach. Instead of trying to get everyone on board at once, identify one teacher who seems likely to be interested and responsive and focus on working with them. When positive changes start occurring in their classroom due to your approach, other teachers will naturally become curious and want to learn more. This can create a snowball effect of buy-in and adoption among the teaching staff.

How did you document the swing session?

Documenting your work with a child like Teddy, who experiences sensory processing challenges, is essential for tracking progress. Focus on the individual child's sensory processing and differences. Note specific observations, such as their interactions with the micro swing, the duration of their engagement with it, and any motor planning challenges or successes you observe. This documentation will help you understand their development and tailor interventions accordingly. Goal writing is also an important aspect of documenting your work, as it provides a clear roadmap for the child's progress.

What about parent participation?

In the context of the DIR Floortime model, involving parents in the therapeutic process is highly valuable. Parent participation can take on various forms, depending on the parents' preferences and the child's needs. It's crucial to recognize that every parent's style may differ. Some parents may be actively engaged and involved in the therapy sessions, participating in interactions with the child alongside the therapist. In contrast, others may prefer to observe the sessions, absorb the techniques, and apply them later. This diversity of engagement styles should be respected and accommodated because parents are key figures in their child's life and need to be comfortable with the process. Understanding each parent's profile and preferences is essential for successful collaboration.

I hope these responses provide clarity and assistance for your inquiries. If you have any more questions or need further information, please feel free to ask.

References

See separate PDF.

Citation

Bennett, L. (2023). Supporting regulation as a foundation for effective therapy. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5646. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com