Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Taking The Lead In Your Practice: Creating A Path Forward Using Evidence-Based Practice, presented by Ingrid Provident, EdD, OTR/L, FAOTA.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate the levels of evidence used in making clinical practice decisions.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine the best ways to integrate evidence-based practice into clinical workflow.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze knowledge translation and its relationship to evidence-based practice.

Introduction

It's a pleasure to be here. Welcome, everyone, as we talk today about how to develop professional competence related to evidence-based practice. Today, we will discuss the different levels of evidence that you may encounter when conducting literature searches and how to best integrate this information into your practice, which is essential for your professional growth and continued competence. Finally, we’ll explore knowledge translation—the process of bridging the gap between when evidence is published and how long it takes to implement changes in practice to achieve the best possible outcomes for our patients. Let’s get started.

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

In 1972, evidence-based practice emerged as a key concept in healthcare, led by a British physician and epidemiologist named Archie Cochrane. This is where it all started for those familiar with the Cochrane databases. Cochrane and his colleagues challenged medical practitioners to enhance their clinical decision-making using the best available evidence. They aimed to create a compilation of research literature so that healthcare practitioners could easily access and apply it in clinical practice to achieve the best possible patient outcomes.

The term “evidence-based practice” is defined as an objective and balanced approach to decision-making where positive outcomes and potential barriers are considered and shared openly. This comprehensive view ensures that patients and practitioners know all aspects of a given intervention, enabling more informed choices.

For those of you working directly with clients, you know it is becoming increasingly important to justify your services. Evidence-based practice is crucial in supporting this effort, as it gives practitioners credible information when explaining various intervention options to patients and their families. The process involves accessing the literature, critically reviewing it to determine its credibility, understanding which policies and practices are most effective, and applying this knowledge to your specific patient population.

EBP is the Best Practice

The terms "best practice" and "what works" are often misunderstood as being interchangeable, but they can differ significantly. Best practice refers to strategies that have been validated and widely accepted, but what works in reality can vary depending on the specific context or setting.

I was educated as an occupational therapist in the 1980s, and the standard practices differ from what we see today. Occupational therapy, like many healthcare fields, has experienced significant and rapid evolution, and the pace of change is only accelerating with advancements in technology and the exponential growth of published research. If practitioners aren’t actively staying informed, it’s easy to fall behind in what is considered current best practice.

Evidence-based practice must encompass three key elements to be effective. First, it needs a definable outcome that can be measured. Second, these outcomes should be meaningful and applicable to real-world clinical settings. Even if a particular intervention is highly effective, it’s of limited use if it cannot be realistically implemented in a clinician’s specific environment. This balances what the literature says and what can be applied in practice, which we will explore more today.

I often hear people say they can’t implement evidence-based practice due to time constraints, lack of resources, or difficulty accessing research. My goal today is to help navigate some of these barriers and make evidence-based practice more approachable and applicable to everyone.

Challenges to EBP

Let’s discuss some of the most common challenges people face when using evidence-based practice. There are many barriers, including lack of access to concise, summarized evidence, not seeing the value of evidence-based practice, considering yourself an expert without needing additional evidence, struggling to understand the evidence or its applicability, not knowing where or how to find it, or simply not having enough time. Today, we’ll discuss strategies to make this more relatable and actionable in clinical settings. I want to provide some tools, resources, and practical ways to integrate evidence-based strategies within limited time frames.

Let’s move forward and address these barriers individually so everyone leaves today with new strategies for overcoming these obstacles.

Strategies to Overcome Obstacles

According to the literature, for evidence-based practice to be truly effective, clinicians must have access to relevant and concisely summarized evidence that is readily available. Many of us are balancing productivity standards and managing heavy caseloads, so quickly finding immediately relevant information that can drive good practice changes is crucial. This aligns with my belief that most clinicians are committed to providing their clients with the best care possible.

Communication among team members is essential to effectively utilizing evidence-based practice. This is where interdisciplinary collaboration comes into play. We’ll explore resources and strategies to integrate evidence-based practice into your team’s routine. Understanding the evidence or its application is challenging, but I’ll offer practical suggestions to help bridge that gap.

Implementing evidence-based practice shouldn’t feel burdensome, especially given the demands of clinical practice. However, resistance to change is a real barrier. Some may feel that adopting new practices is overwhelming or unnecessary. But for those who embrace change and see it as an opportunity for growth, this won’t be as challenging.

For many, the greatest challenge seems to be a lack of time. This brings us to a key question: how can we incorporate evidence-based practices into daily routines to minimize time constraints?

I aim to provide you with strategies to streamline this process so that evidence-based practice becomes part of your routine rather than an additional task. By integrating these strategies, we can ensure that time is less of a limiting factor.

Process of EBP

- Ask: Identify a clinical problem.

- Attain: Review relevant literature.

- Appraise: Critically appraise evidence.

- Apply: Evaluate the need for practice change and potential implementation.

- Assess: Evaluate outcomes.

- EBP ALWAYS begins and ENDS with the patient.

The process of evidence-based practice always begins with a clinical question. From there, it involves searching for and critically appraising the evidence. Let’s say your team identifies a problem—perhaps a programmatic element isn’t working as intended. At this point, a practice change might be necessary. The next step is to review the relevant literature and determine whether it supports making that change.

Once you’ve found relevant research, the goal is to critically appraise it—to read, understand, and decide if it applies to your particular case or setting. Does it align with the clinical scenario you’re dealing with? If so, you move forward by implementing the change and evaluating whether it results in the desired outcome.

The process is straightforward. You start by asking a question and identifying the clinical problem. Next, you search for and review the literature, critically appraise it for its relevance, and then consider how these findings can be applied in your context—whether it’s for a specific patient or a broader programmatic issue. Finally, you implement the change and assess its impact.

The ultimate aim is to provide the best intervention and monitor whether the outcomes reflect meaningful progress for the patient. By breaking down each step, we ensure that evidence-based practice remains patient-centered and focused on achieving optimal results. We’ll review each step in detail to see how they work individually and together.

ASK a Relevant Question

When clinicians set out to ask a relevant question, they often use what is known as a foreground question—a question that is directly related to impacting treatment. One commonly used format for structuring these questions is the PICO framework. You may have heard colleagues ask, "What’s your PICO question?"

The PICO format helps to clearly define the key elements of a clinical inquiry:

- P stands for the patient or the problem. It always begins by identifying the patient group or the specific issue you want to address.

- I stands for intervention. This element defines the treatment or approach you are considering to see if there are better alternatives or new strategies.

- C stands for comparison. This component is optional. Sometimes, you want to compare the intervention against another treatment, a placebo, or the current standard of care. If there is no comparison, it’s a PIO question instead of a full PICO.

- O stands for the outcome. This defines what you hope to achieve with the intervention, such as improved function, reduced symptoms, or enhanced quality of life.

You can craft a focused question using the PICO format; these keywords become the search terms for exploring the literature. This structured approach ensures that the search is precise and that the evidence gathered is relevant to your clinical question.

Find and Review Relevant Literature

Once you’ve formulated your clinical question, the next step is determining where to find the relevant literature. You may be familiar with PubMed, CINAHL, or the Cochrane Library databases. If you’ve been in an academic program within the last five to ten years, you were likely encouraged to explore these evidence-based databases as part of your training to meet the ACOTE standards.

However, many clinicians find that they can no longer access these resources once they leave academia, which can feel like a significant barrier. While some facilities still maintain medical libraries, this is not always true. During my early career days, I was fortunate to work in a hospital with a large medical library and skilled librarians who were invaluable in helping identify and retrieve articles for us to review. Not everyone has that type of support available, though.

The good news is that if you can access a computer, you can access Google. Specifically, I recommend utilizing Google Scholar, a specialized search engine for scholarly literature. If you’ve never used it, try it—just type “Google Scholar” in your search bar, navigate to the page, and begin typing in the keywords related to your clinical question. Google Scholar is a great option if you can’t access other academic search engines.

Additionally, if you are a member of a professional association such as AOTA, APTA, or ASHA or work with colleagues who belong to these organizations, you may have access to their professional literature databases. For occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), NBCOT has also included ProQuest as a searchable database within its resources, which is a valuable tool for evidence-based practice.

Boolean Operators for Limiting or Expanding Searches

The second step in the evidence-based practice process is to search for the literature; knowing how to refine your search is crucial. One way to do this is through the use of Boolean operators. Let’s go through these terms, which help you narrow or expand your search depending on your search.

Operator | Example | What it does |

AND | Luke AND Leia | Searches for results containing both Luke and Leia: (Narrows the search) |

OR | Anakin OR Vader | Searches for results containing either Anakin or Vader: (Broadens the search) |

NOT | C-3PO NOT R2-D2 | Searches for results containing C-3PO but excludes results containing R-2D2 |

“” | "Han Solo" | Searches for results containing the exact phrase, "Han Solo" |

NEAR/N | Jedi NEAR/5 lightsaber | Searches for results where lightsaber is within 5 words of Jedi |

* | Light* | Looks for results containing the root word "light,” including light, lightsaber, light speed, etc. |

() | ("Ben Solo" OR "Kylo Ren") AND "high pants" | Groups similar concepts together. This will search for results containing either "Ben Solo" or "Kylo Ren", and "high pants." |

If you use the operator "AND" between two keywords, the database will only return results containing both words. This narrows your search, ensuring that all results include exactly what you seek. For example, if you search for “fall prevention AND elderly,” only articles containing both terms will be displayed.

Conversely, using the operator "OR" broadens your search, as it will find results containing either of the terms you’ve used. This is useful when you include multiple related concepts, such as searching for “children OR adolescents.” The results will include sources that mention either term, giving you a broader pool of information.

If a specific term keeps appearing in your search but isn’t relevant to your needs, you can use the "NOT" operator to exclude it. For example, if you are searching for "Alzheimer’s disease, NOT Parkinson’s," it will exclude any results that contain “Parkinson’s.” This tool helps filter out unrelated results, refining your search.

Quotation marks ("") help you find an exact phrase. By placing your search term in quotes, such as “patient-centered care,” the search engine will look specifically for that phrase, ensuring that only results containing the exact wording appear.

You may have noticed an example using the term "NEAR/n." This operator allows you to find results where two words are located near each other in the text. For instance, “stroke NEAR/5 rehabilitation” will only display results where “rehabilitation” is within five words of “stroke.” It’s a more sophisticated way to limit your search when you have too many results.

Another useful tool is the asterisk (*), which serves as a wildcard to capture different root word forms. For example, if you use “occup*” as a search term, it will return results for “occupation,” “occupational,” or “occupational therapy.” This is helpful when you want to include term variations without typing each one individually.

Lastly, parentheses ( ) are used to group similar concepts. This is particularly effective for complex searches that involve multiple Boolean operators. For example, a search like “(therapy OR intervention) AND (child* OR pediatric)” will return results that combine related concepts, helping you structure a more comprehensive search.

If you’re new to using these search strategies, experimenting with different combinations of these operators can significantly refine your search results and make your literature review more efficient and targeted. It’s a valuable skill to master as you gather evidence to inform your clinical practice.

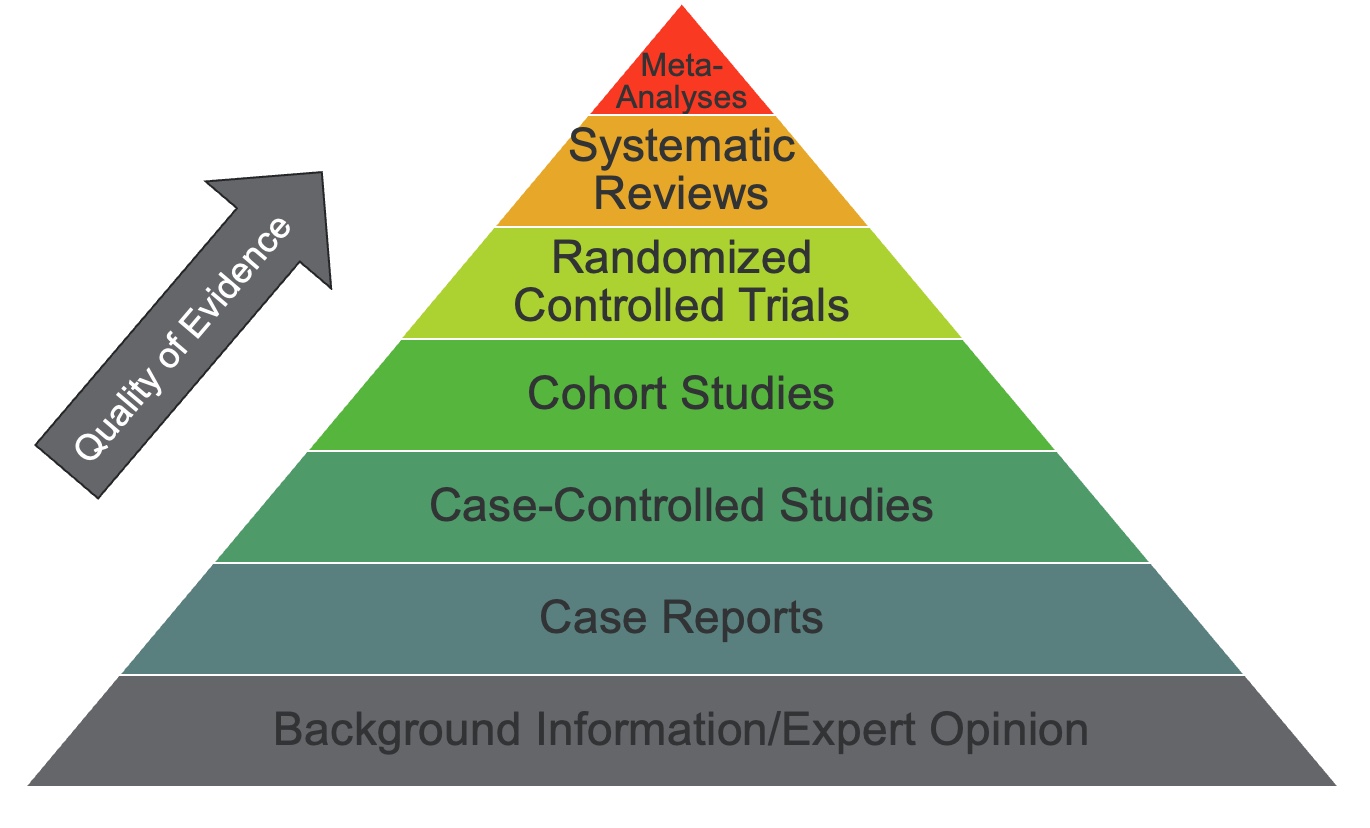

Levels of Evidence: The Pyramid of Evidence

One of the foundational elements of evidence-based practice is understanding the different levels of evidence, which are often depicted in a hierarchical pyramid. This pyramid in Figure 1 is widely referenced in the literature and serves as a visual guide for clinicians to understand the varying strengths of research evidence.

Figure 1. The pyramid of evidence (Click here to enlarge the image).

Let’s break it down, starting from the base. As with any pyramid or triangle, the foundation is at the bottom, supporting the rest of the structure. Background information and expert opinion are at the bottom of the evidence-based practice pyramid. While expert opinion can be valuable—especially from clinicians with extensive experience, like those with 30 or more years in practice—this type of evidence is considered the lowest level. It is primarily based on personal skill development and anecdotal knowledge gained from years of clinical work rather than on formal scientific investigation.

Moving up a step, we find case reports or case studies. These involve thoroughly examining a single person’s experience with a specific intervention. Although they provide rich clinical insight, they are based on an "n" of one, which limits their ability to be generalized to broader populations.

One level above case studies are case-control studies. These involve comparing individuals with a specific condition to a matched group without the condition, allowing researchers to look for correlations and potential causal factors. These studies begin to introduce more scientific rigor but still lack some of the controls seen in higher levels of evidence.

Further up the pyramid are cohort studies. In these studies, a group of people is followed to observe how different factors impact outcomes. Cohort studies often help identify risk factors and track the natural progression of a condition, providing stronger evidence than case-control studies.

We have the highest levels of evidence at the top of the pyramid. This includes randomized controlled trials (RCTs), considered the gold standard in research design. RCTs use random assignment and control groups to test specific interventions, minimizing bias and allowing for clearer conclusions about cause and effect.

The above RCTs are systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These are considered the pinnacle of evidence because they aggregate data from multiple studies that have tested similar interventions. Systematic reviews meticulously summarize findings, while meta-analyses use statistical methods to combine results, providing a more comprehensive picture of what is working, what isn’t, and why. These reviews are critical because they synthesize large volumes of research into concise conclusions, making it easier for clinicians to apply findings to practice.

It’s important to recognize that not all levels of evidence carry the same weight. As you move up the pyramid, the level of scientific rigor increases, enhancing the findings' reliability and applicability. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top provide the strongest guidance for practice because they offer a comprehensive view of the evidence and help identify trends and gaps in the research. Understanding this hierarchy is essential when determining the strength of the literature you use to inform clinical decisions.

AOTA Resources for EBP

If you are a member of AOTA, they offer a wide range of evidence-based practice resources specifically designed for OTPs. While I’m not here as an official representative of AOTA, I want to highlight the benefits of leveraging these resources if you or a colleague is a member. Often, even if only one person on the team is a professional association member, the resources they have access to can be shared within the group to help integrate evidence-based practice into your clinical setting.

AOTA provides various tools for evidence-based practice and knowledge translation. These include diagnosis-specific practice guidelines that guide interventions for particular patient populations. They also offer systematic reviews—one of the highest levels of evidence we discussed earlier. Systematic reviews comprehensively analyze multiple studies on a topic, making them valuable resources for informed decision-making. Additionally, AOTA has a resource called Evidence Connection, which translates research findings into practical applications for different clinical populations.

Utilizing these resources can help streamline the integration of evidence-based strategies into practice and ensure that interventions are grounded in the most current and robust evidence.

NBCOT

If you maintain your NBCOT certification, you can access several of these resources at no additional cost. For example, NBCOT provides access to databases where you can easily find articles that support clinical decision-making and enhance your practice. These resources allow you to stay up-to-date with current research and integrate it into your treatment strategies without additional subscriptions. These tools ensure you apply the best evidence in your practice, ultimately leading to better client outcomes.

Interdisciplinary EBP Resources

There are also freely accessible interdisciplinary evidence-based practice resources, such as the Aging and Disability Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (ADEPP). ADEPP aims to improve access to information on evidence-based interventions, particularly for aging and disabled populations. Its goal is to decrease the lag between when new research is published and when it is adopted in clinical practice. Offering these resources aims to streamline knowledge translation and promote quicker implementation of effective strategies.

Another valuable resource is Healthy People 2030, a government initiative that provides evidence-based resources organized by specific health topics. Their website features a range of studies and interventions that are directly relevant to the goals outlined in Healthy People 2030. This resource is particularly useful for OTPs as we work towards meeting these objectives and implementing high-quality, research-supported interventions in our practice.

Knowledge Translation/Effective Knowledge Translation

I’ve mentioned knowledge translation a few times. While the term itself originated in the field of public health, it’s relatively new. However, it addresses an ongoing issue: the underutilization of evidence-based research. Knowledge translation describes the gap between what is known through research and what is being implemented in practice.

Some recent literature suggests that this gap can be as long as 15 years between when research findings become available and when they are commonly applied in clinical settings. That’s a significant delay, raising concerns about whether patients receive the most up-to-date and effective care. This lag indicates a need for clinicians to prioritize staying current with new research, continually integrating it into their professional development and actively working to reduce this gap to ensure the best possible outcomes for their patients.

So, how can we minimize this gap and make knowledge translation more effective? What strategies can clinicians incorporate into their daily routines to bridge this divide? I have a few key approaches we can explore further. We’ll examine these strategies in more detail to see how they can be integrated into your practice routines.

Interdisciplinary Journal Clubs

Effective knowledge translation can be facilitated through strategies such as interdisciplinary journal clubs. These can be set up in a format like a "lunch and learn," with a different person or discipline taking the lead each time. Journal clubs can be held monthly or quarterly—whatever frequency works best for your setting. The key is consistency; the more regularly they are done, the more they become part of your team’s routine.

I previously mentioned some of AOTA’s resources, and one tool worth highlighting is the Knowledge Translation Toolkit, specifically designed to help reduce the gap between research and practice. On a broader scale, there are established theoretical frameworks, such as the Knowledge to Action framework, which maps out how new knowledge is created and the long process of translating it into practice. Another framework is the PARiHS model, which stands for Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services. It provides a structured approach to implementing research into health services and could be a great starting point for teams looking to enhance their practice.

Creating an interdisciplinary journal club is an easy and practical way to start. Even if the participants are relatively new to evidence-based practice, working together in a group setting can foster a collaborative environment. Professionals from different disciplines treating similar patient populations, such as a neurology team working with CVA clients, can benefit greatly from discussing new interventions and exploring relevant literature. For example, the team could look at research on a new intervention, analyze the outcomes, and discuss how they measured the effects—leading to a rich exchange of ideas and a deeper understanding of how evidence could inform their practice.

The structure of a journal club can vary based on the setting. It might start simply by introducing participants to different levels of evidence or exploring effective search strategies. For example, team members could take a clinical topic, break it down into keywords, conduct their searches, and bring back the resources they find to share with the group. This approach builds confidence in literature searching and critical appraisal skills.

From there, the group can develop and prioritize clinical practice topics that are relevant to their setting. For example, if the team wants to design a multimodal fall prevention program, they could review what is effective in the literature and build the program based on these findings. A journal club coordinator can streamline this process by managing logistics, like scheduling meetings, organizing materials, or even just ordering lunch to create a welcoming atmosphere.

The coordinator can also help by selecting and distributing relevant articles ahead of time. Sharing full-text articles by email allows members to review the content before the meeting, making the discussion more productive. During the session, members review the article, discuss its findings, and consider its clinical relevance: Does this apply to our patient population? Could we implement this in our current practice?

A journal club helps build a culture of collaboration and shared learning among team members through these discussions. It encourages clinicians to stay current, apply new knowledge, and contribute to ongoing professional development—all while enhancing patient care.

AOTA’s Knowledge Translation Toolkit

AOTA offers a Knowledge Translation Toolkit to address clinicians' challenges when implementing evidence-based practices.

Table 1. Knowledge Translation Barriers and Associated Knowledge Translation Toolkit Resources | |

Major knowledge translation barriers | Knowledge Translation Toolkit resources to overcome barriers |

Lack of knowledge about current research findings | Guides for holding knowledge-sharing activities in local communities |

Lack of access to information | How-to videos for accessing "open access" peer-reviewed articles |

Insufficient time and resources | Recommended strategies to maximize time while conducting literature reviews |

Lack of leadership engagement | Suggestions for how to collaborate with leadership and align knowledge |

Lack of readiness or willingness to implement new programs | Steps for establishing knowledge translation "champions" to inspire change |

We’ve discussed some barriers to evidence-based practice, but knowledge translation has its obstacles, particularly the lag between when new research is published and when it’s used. For example, if there is a lack of awareness about current research, AOTA has created guides that outline ways to disseminate knowledge through local communities and facilities.

If you’re looking for open-access, peer-reviewed articles that anyone can access without a journal subscription, Google Scholar is a great tool, as it pulls from unrestricted sources. AOTA also has instructional videos on navigating open-access databases and locating relevant journals, which can be especially helpful if accessing current research feels overwhelming.

For those who don’t have enough time or resources to sift through many articles, AOTA provides strategies for streamlining your search process. By using more targeted keywords and search terms, you can minimize the number of unrelated articles that show up, making your review process more efficient.

Another common barrier is a lack of administrative support or insufficient backing from leadership. When high productivity demands, it’s challenging to carve out time for professional development activities like knowledge translation. AOTA offers guidance on engaging leadership in these efforts by demonstrating how investing in knowledge translation can enhance patient outcomes, promote best practices, and potentially make your facility more competitive.

Finally, if your colleagues resist change, AOTA’s resources include steps for establishing champions within the organization—individuals who can lead by example and encourage others to embrace new practices. These leaders can help foster a culture that values ongoing professional development and evidence-based care.

Although I can’t delve into the full scope of these resources here, knowing where to find them is an excellent starting point for those interested in integrating more evidence into your clinical work. AOTA’s website is a great place to explore these options further, especially if you want to overcome specific barriers and promote best practices in your setting.

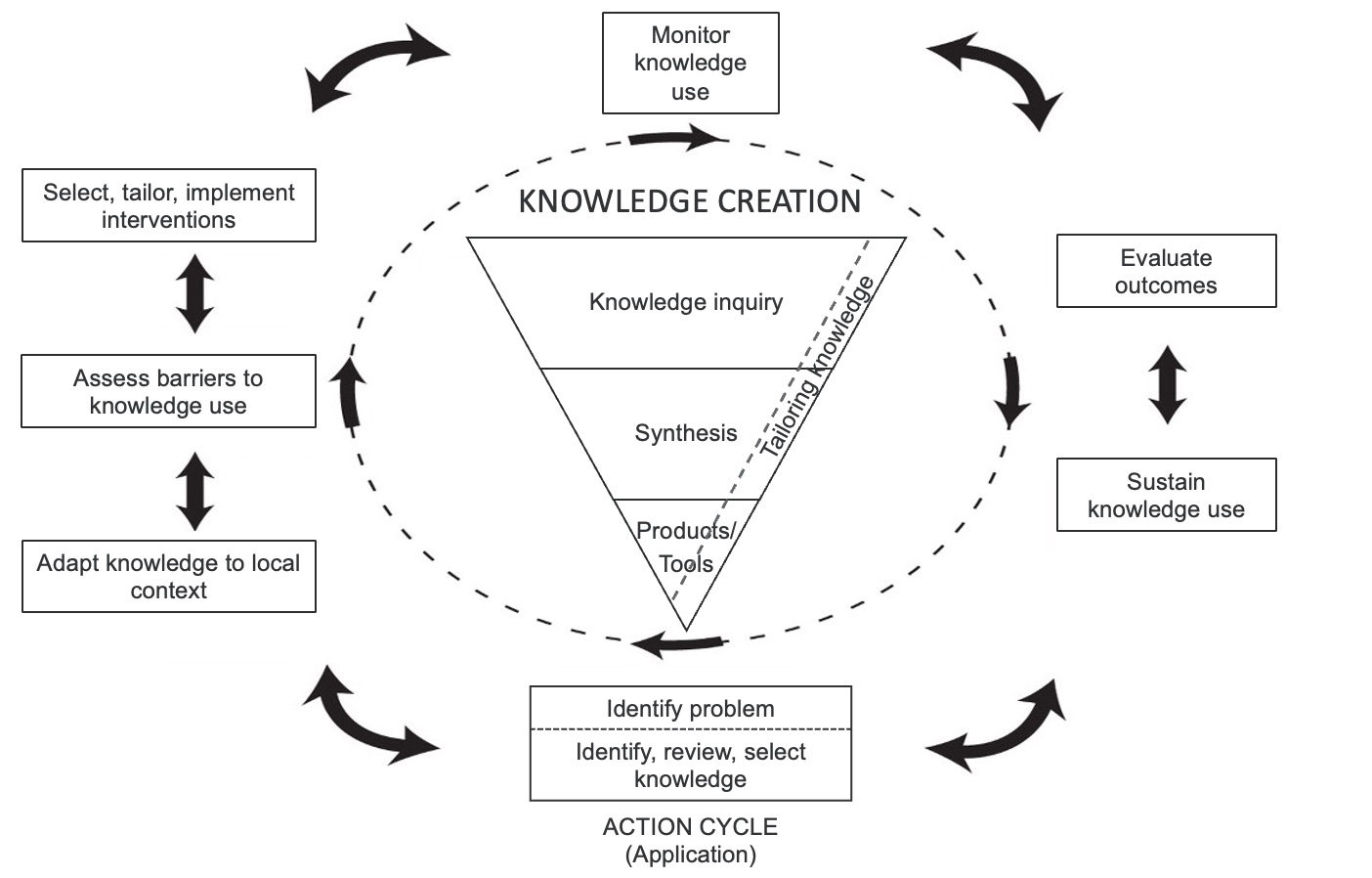

The Knowledge-to-Action Framework

The Knowledge-to-Action Framework (Figure 2) is valuable for understanding how evidence moves from research into practice.

Figure 2. The Knowledge-to-Action Framework (Click here to enlarge the image).

It begins with the core of knowledge creation, where scientists, researchers, and clinicians in teaching hospitals or research facilities start by posing a clinical inquiry—asking, “What might happen if...?” From there, they conduct studies, analyze outcomes, and generate the literature that forms the foundation of evidence-based practice.

Once that research is published, the next step involves clinicians like us. The framework’s outer circle outlines how practitioners apply this knowledge to practice. It starts by identifying a specific problem in your setting and defining the keywords to guide your search for relevant literature. After finding evidence that addresses the issue, the focus shifts to applying the knowledge, testing new interventions, and identifying possible barriers.

As you implement these strategies, you might need to tailor or adapt the programs based on the unique needs of your clients or the clinical environment. At this point, evaluating the outcomes becomes crucial—monitoring whether the changes lead to the desired results. This evaluation often reveals areas for further refinement, leading to ongoing adjustments and improvements.

This process is cyclical, as new insights and findings continually reshape practice. The Knowledge to Action framework illustrates that knowledge translation is not a linear process but a dynamic, ongoing cycle of inquiry, application, evaluation, and refinement. While theoretical, this approach is practical in guiding how research can be systematically integrated into daily clinical practice, leading to meaningful and sustained practice changes over time.

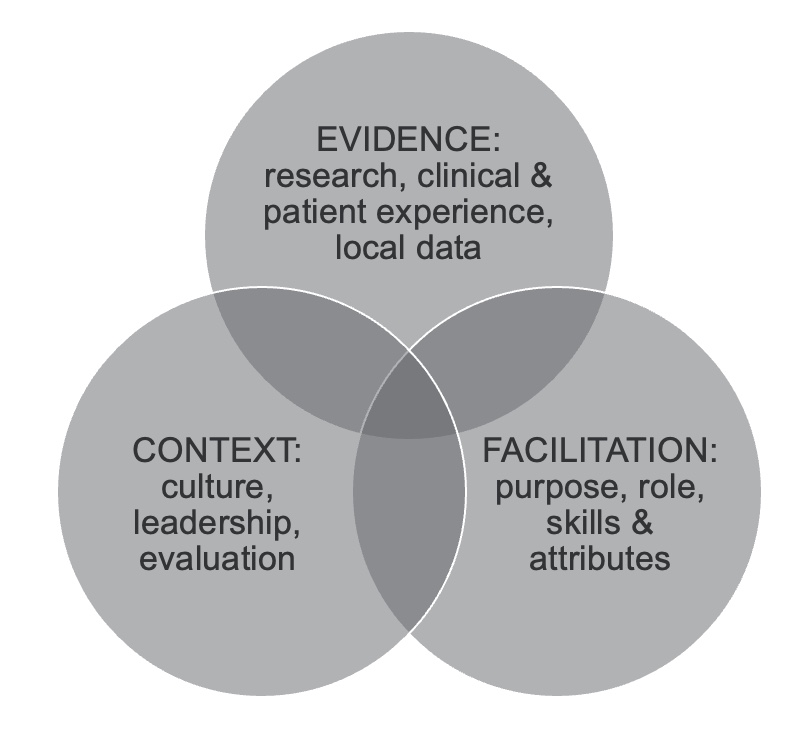

PARIHS Framework

The PARiHS (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) framework takes a broader, more prescriptive approach to understanding how evidence is effectively implemented in clinical settings (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The PARiHS Framework.

Like other models, it recognizes that evidence is rooted in research, clinical expertise, and patient experiences. However, it uniquely emphasizes how these elements intersect and how data should be accessible and applicable to diverse contexts.

We live in a time when technology enables us to access research worldwide, offering insights into similar issues in different healthcare settings. The PARiHS framework leverages this global perspective by examining how cultural differences and varying contexts influence the application of research. It emphasizes that successful implementation depends on several key factors: the strength and type of evidence available, the context in which it is applied, and the support or facilitation needed to make the change happen.

The model considers how the nature of the evidence—whether from high-quality randomized controlled trials or observational studies—impacts its applicability. It also looks at the context, which includes the specific healthcare environment, local policies, and the team's readiness. Lastly, it highlights the role of internal and external facilitators—individuals who actively work to champion and guide the change process, whether they are part of the organization or brought in specifically to support implementation.

The PARiHS framework provides a comprehensive view of how evidence, context, and facilitation intersect to shape the implementation process. It’s a broader, "big-picture" model that acknowledges the complexity of translating research into practice across diverse settings. This helps us understand that for an intervention to be successfully adopted, it must be adapted to fit the unique needs and resources of each clinical environment, with strong leadership and facilitation driving the process.

Case Application

Let’s bring everything we’ve discussed into a real-world scenario. I’d like to illustrate the process using a geriatric case example. Naomi is a 78-year-old woman who has been experiencing memory loss and recently fell a flight of stairs at home. She currently lives alone and wants to return home safely.

How Can EBP Assist the Process?

A team of clinicians—including a physical therapist, an occupational therapy practitioner, and a speech-language pathologist—wants to use evidence-based practice to guide Naomi’s intervention plan. To do so, they start by developing a clear clinical question using the PICO framework, or in this instance, a PIO (Patient, Intervention, Outcome) format, since a direct comparison is unnecessary.

The key elements they define are:

- Patient: An elderly adult with memory issues and a head injury

- Intervention: Fall prevention strategies

- Outcome: Safe return to independent living at home

Using these components, the team begins their literature search by focusing on keywords such as “fall prevention in the elderly,” “cognitive impairment and fall risk,” and “interventions for head injury in older adults.” From here, they can refine the search based on relevant findings and select high-quality evidence to build Naomi’s personalized intervention plan.

The goal is to identify evidence that integrates fall prevention strategies with cognitive support and safety modifications, ultimately allowing Naomi to achieve the desired outcome of returning to her home environment safely. This approach ensures that Naomi receives the most appropriate and effective interventions and models how an interdisciplinary team can use a structured evidence-based process to inform clinical decisions and optimize patient outcomes.

Literature Search

To promote a successful transition from the skilled nursing facility to Naomi’s home, the interdisciplinary team has crafted their clinical question and will now conduct a literature search using the defined keywords.

One of the top results of this search was an open-access article titled *Home and Environmental Hazard Modifications for Fall Prevention Among the Elderly*. Based on the title, it appeared to be highly relevant to Naomi’s case. The article focuses on practical strategies for modifying home environments to minimize fall risk, which is essential given Naomi’s recent head injury and cognitive challenges.

The team's next step would be to critically appraise the article to determine the strength of the evidence and its applicability to Naomi’s specific needs. They would use these insights to develop a comprehensive intervention plan that addresses home modifications, safety strategies, and any additional support needed to facilitate her return to a safe and functional home environment.

Monthly Interdisciplinary Journal Club

If you uncover an article like that, it might be an excellent choice for a journal club. Everyone would read it, review the evidence presented, examine the methods used to gather data and discuss the outcomes. The article might suggest additional modifications that could support Naomi’s transition back into her home.

You can see how this evidence directly applies to the patient. Remember, evidence-based practice always begins with the patient, and the goal is to identify outcomes that can be applied to their specific intervention plan. In a monthly interdisciplinary journal club, the article could be printed or emailed to all members beforehand so they can read it in preparation for a productive discussion.

Additional Resources Found

The physical therapist might access the APTA website to find additional resources related to fall management, while the OTP could pull evidence from the AOTA website. The speech-language pathologist could use ASHA resources to identify evidence-based strategies from their specific field. Each professional would consider the most relevant interventions for addressing Naomi’s memory issues and decreased cognitive status as part of the fall prevention program.

The team could then gather for a 60-minute lunchtime meeting or discussion to share what they found in their discipline-specific literature. This allows them to collectively refine the treatment plan to best support Naomi’s transition back home, with the shared goal of maximizing her safety and independence through targeted fall prevention strategies.

For example, APTA has evidence briefs addressing fall risk in community-dwelling elders, providing valuable insights for the physical therapist. The AOTA website offers resources such as handouts on fall prevention for older adults, which can be shared with family members and caregivers. However, considering Naomi’s memory issues, simply providing written information might not be sufficient. It’s important to consider potential health literacy concerns and adapt resources as needed.

For speech-language pathology, resources may include strategies for improving communication around safety and memory support for clients at risk of falls. Each discipline contributes unique perspectives and tools, ensuring a well-rounded plan tailored to Naomi’s needs.

Critically Appraise the Evidence

So, again, three distinct resources could be discussed, all related to a specific patient within a lunch-and-learn series. A few simple but critical questions could guide therapists: Were the results of the original article valid? How precise were those results? Most importantly, are these findings applicable to Naomi’s case? This approach encourages clinicians to critically evaluate whether the evidence truly fits the needs of this particular individual.

Programmatic Changes

The resources they uncovered could point to programmatic enhancements for their fall prevention program to ensure it covers all aspects of fall prevention. For any elderly clients preparing to return home, the team must determine how best to provide comprehensive rehabilitative strategies and environmental modifications to create a robust fall prevention plan—both in the skilled nursing facility and for the transition back home.

If a group is particularly interested in this topic, they could lead in developing a new program, training other team members, building a cohesive team approach, and ensuring consistent implementation. Measuring the outcomes would also be key, as falls are a significant concern in assisted living and skilled nursing facilities. High fall rates can lead to penalties for these facilities, making it critical to continuously evaluate and refine the program.

Promoting and marketing the program could also help differentiate the facility or team, highlighting their commitment to quality care and safety. Taking these extra steps supports professional development and helps prevent burnout by breaking the monotony of repetitive tasks and encouraging staff to engage in innovative, evidence-based initiatives.

Evidence-Based Practice

Integrating evidence-based practice and initiating changes within your setting can be a challenge—but it can also be the “just-right” challenge, depending on where you are in your professional development. Evidence-based practice allows therapists to use up-to-date interventions, enhancing patient care and building professional competence. It can serve as a differentiator, helping individuals stand out in their development. Setting goals around new areas of interest or improvements you want to make during your upcoming evaluation can motivate and contribute to growth.

Evidence-based practice is always patient-centered, focusing on individualized care and promoting knowledge translation. The aim is to reduce the gap between new evidence and its application in clinical settings. Your clinical interventions should not look the same as ten years ago. Medical care has made significant advancements, and ensuring that all therapists are equipped with the latest evidence is essential.

Implementing evidence-based practices facilitates better clinical decision-making and is even more powerful in an interdisciplinary manner, as it highlights each discipline’s unique contributions to the team. It promotes the quality, efficiency, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of interventions while minimizing the risk of harm to patients. Evidence-based practice is cost-effective and, ultimately, leads to improved patient outcomes.

Final Thoughts

So, as we wrap up, I invite everyone to think about how you might start integrating evidence-based practice into your current routines. Consider whether you are incorporating these discussions within your discipline or, ideally, in an interdisciplinary setting. Have any of you had success implementing journal clubs?

How are you integrating evidence-based practice into your student programs? Many of us take on fieldwork students who often have strong skills in searching the literature. A starting point could be using fieldwork students to lead in-services on literature searches or available resources in your facility.

Incorporating best practices or evidence discussions into every team meeting is another strategy. It doesn’t always need to come from a leader—everyone can contribute. It’s about making it part of the routine, like starting a new exercise program or healthy habit. It doesn't feel as overwhelming when it becomes a regular part of the workday.

Sharing articles at monthly meetings is an excellent place to start. Creating a list of topics that people want to learn more about and then rotating presenters helps ease people into the process. You don’t have to be an expert to discuss an article—simply bringing up questions or insights encourages a more informed dialogue.

Monthly evidence-based practice journal clubs are a great way to create excitement around learning and keep evidence-based practice at the forefront within your facility. Another idea shared is starting an evidence-based practice committee in a school district, where members work together to bridge the knowledge translation gap.

Discussing evidence informally with coworkers during client collaboration is another way. Sometimes, these brief exchanges spark new ideas. Another shared that reviewing articles and taking continuing education courses helps refine their approach to students. Sharing articles via email and discussing them at monthly meetings when time permits is another simple but effective strategy.

Setting smaller, manageable goals, like reading one new article a month or making time for a focused search each week, is an excellent approach. Journal clubs sometimes get canceled in acute care settings due to the demanding pace, but having a binder of articles accessible for review can keep evidence-based practice visible.

At this point, I want to ensure that the learning outcomes for today’s session have been met. We differentiated the various levels of evidence, explored strategies for integrating evidence-based practice into the clinical workflow, and discussed knowledge translation and its relationship to evidence-based practice. Now, let’s review some questions and their answers, which will be part of the exam for earning credit for the time you’ve spent here.

Exam Poll

1)Evidence-based practice is...

Evidence-based practice is the objective, balanced, and responsible use of current research evidence and the best available data to guide policy and practice decisions, ensuring improved outcomes for consumers, patients, and clients. Therefore, the correct answer is D.

2)Which is NOT a challenge when implementing evidence-based practice into practice?

Remember, our challenges were things like resistance to change. So, embracing change is not considered a challenge. Embracing change would be a person that wants to, you know, do something a little bit different. Lack of time was considered one of those challenges. And many of you stated that access to concisely summarized evidence was a challenge for you. Not everybody knows how and where to get that and then understands how it is applied to a patient population. So when you look at this question and the questions you will take afterward, remember that it's not a challenge if you embrace change. The challenge will be if you are resistant to change. So the correct answer for question number two is a.

3)What should evidence-based practice always begin and end with?

Evidence-based practice always begins and ends with the patient. The clinical question should be formulated based on the patient’s problem or situation, and any changes or interventions applied should ultimately benefit the patient. Therefore, the correct answer for question three is the patient or B.

4)Which is the highest quality of evidence?

The pyramid we reviewed in the presentation lists various levels of evidence, and the options for this question are case studies, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, or cohort studies. The highest level of evidence is meta-analysis, which provides the most robust data for making informed clinical decisions.

5)What is an effective method of knowledge translation?

All of the above is the correct answer. In all of the listings above, there would be effective ways to minimize that time gap between published literature and its application to the individual.

Questions and Answers

I work in a school setting with a very limited interdisciplinary team: I’m the only OT practitioner, there’s no PT and only a halftime SLP. Do you have any suggestions for creating a journal club or similar professional development opportunities?

This is a common challenge in smaller settings. Here are a few strategies you could try:

- Reach Out to Nearby Schools: Contact other schools in your area and see if other professionals might be interested in collaborating. Building a network with other school-based OTs, SLPs, and PTs can create opportunities for a broader journal club or discussion group.

- Collaborate with Your SLP: If the other schools don’t have interested professionals, consider forming a small group with the part-time speech-language pathologist at your school. Even with just two people, you can create a meaningful dialogue by meeting monthly—perhaps online in the evenings or briefly in person—to discuss recent articles or resources.

- Create a Shared Notebook: If your team members work different hours and don’t overlap, consider setting up a shared notebook in a common space. Use it to jot down ideas, questions, or interesting findings from your practice sessions. This can serve as an ongoing conversation starter and resource list for anyone who comes across it.

- Leverage Professional Associations: Use professional associations to sponsor online discussion groups like AOTA’s school-based practice forums. These platforms often have members in similar settings and can provide additional insights and resources.

- Explore the Literature Independently: When in-person collaboration is not feasible, regularly searching and reviewing literature on interventions and techniques applicable to your students can still be beneficial. This helps you stay updated and informed, even when traditional journal clubs aren’t an option.

Overall, focus on creative ways to connect through networks, shared resources, or virtual meetings to ensure you have professional support and opportunities to learn from others.

References

Bar-Nizan, T., Rand, D., & Lahav, Y. (2024). Implementation of evidence-based practice and burnout among occupational therapists: The role of self-efficacy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2024.050426

Bernhardsson, S., Lynch, E., Dizon, J. M., Fernandes, J., Gonzalez-Suarez, C., Lizarondo, L., Luker, J., Wiles, L., & Grimmer, K. (2017). Advancing evidence-based practice in physical therapy settings: Multinational perspectives on implementation strategies and interventions. Physical Therapy, 97(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20160141

•Burke, H. K., Bundy, A. C., & Lane, S. J. (2023). If reasoning, reflection, and evidence-based practice are essential to practice, we must define them. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.2044

Field, B., Booth, A., Ilott, I., & Gerrish, K. (2014). Using the knowledge to action framework in practice: A citation analysis and systematic review. Implementation Science, 9, Article 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0172-2

Juckett, L. A., et al. (2021). Translating knowledge to optimize value-based occupational therapy: Strategies for educators, practitioners, and researchers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(6), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.756003

Kinney, A. R., Havrilla, E., Hack, L. M., Lowman, J. D., Hornyak, J. E., & Velozo, C. A. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to the adoption of evidence-based interventions for adults within occupational and physical therapy practice settings: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 104(7), 1132–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.005

Lin, S. H., Murphy, S. L., & Robinson, J. C. (2010). Facilitating evidence-based practice: Process, strategies, and resources. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(1), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.1.164

McCurtin, A., & Clifford, A. M. (2015). What are the primary influences on treatment decisions? How does this reflect on evidence-based practice? Indications from the discipline of speech and language therapy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 21(6), 1178–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12385

Morton Ninomiya, M. E., Atkinson, D., Brascoupé, S., Firestone, M., Robinson, N., Reading, J., Ziegler, C. P., Maddox, R., & Smylie, J. K. (2017). Effective knowledge translation approaches and practices in Indigenous health research: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), Article 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0430-x

Valera-Gran, D., Campos-Sánchez, I., Prieto-Botella, D., Fernández-Pires, P., Hurtado-Pomares, M., Juárez-Leal, I., Peral-Gómez, P., & Navarrete-Muñoz, E. M. (2024). Enhancing evidence-based practice into healthcare: Exploring the role of scientific skills in occupational therapists. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(1), Article 2323205. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2024.2323205

Citation

Provident, I. (2024). Taking the lead in your practice: Creating a path forward using evidence-based practice. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5747. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com