Introduction and Overview

Thank you for joining me today as we discuss the difficult and sensitive topic of death and dying. When I was in physical therapy school, we didn't explicitly talk about what to do if a patient dies. We may have glossed over the topic of death when learning about pathologies that were chronic and progressive or fatal, however, we did not address how to handle it. It wasn't until a patient of mine passed away that I realized, as a PT working primarily in hospitals, this was probably going to happen a lot. I had no idea how to approach the situation. Should I be sad or upset? Everyone else was going about their day as if nothing had happened. Was I supposed to react the same way? How was I supposed to process all these feelings? At that point in my life, I was quite young. I had not had much experience with death and dying. I had not had any close friends who had died. My family has a history of longevity, so I'd only had very old relatives die. I was confused as to how to process those feelings.

The Ubiquity of Death

In life, not everyone will get married. Not all of us will have chronic health conditions like diabetes. Not all of us will have children. The one thing that unifies all human beings is that we are mortal. We will die. We have no idea when that will happen. Despite the fact that death is the one thing we all have in common, in Western culture (especially in the United States), we tend to avoid talking about dying. Regardless of how a person lives their life, how old they are, what they've done, what they haven't done, all of us are going to die.

As evidenced by these recent tweets, this topic isn't going away any time soon:

"The right time to have an end of life discussion was last week or last month, but today will do." Mark Reid, MD, @medicalaxioms, July 2014

"American mortality holding steady at 100%." Louise Aronson, @LouiseAronson, October 2014

Role of Therapy

The following quote is from an article that was published in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) nearly 40 years ago:

If medicine takes aim at death prevention, rather than at health and relief of suffering, if it regards every death as premature, as a failure of today's medicine - but avoidable by tomorrow's - then it is tacitly asserting that its true goal is bodily immortality... Physicians should try to keep their eyes on the main business, restoring and correcting what can be corrected and restored, always acknowledging that death will and must come, that health is a mortal good, and that as embodied beings we are fragile beings that must stop sooner or later, medicine or no medicine (Kass, 1980).

As therapists working with patients, it is important that we understand what can be corrected and restored. That is the essence of rehabilitation. It shouldn't matter where the person is on their life trajectory. If something can be corrected and restored, it is our opportunity to find that and to do our best to correct it and restore it.

When to Cease Intervention

Haider Warraich, an emergency room physician, wrote a book titled Modern Death: How Medicine Changed the End of Life. In a January 2017 National Public Radio interview, Warraich was quoted as saying:

Warraich's comment is astute and relevant with respect to today's modern medicine. Especially for critically ill patients who require a lot of interventions, we know how to turn on a ventilator and intubate someone. We know when to start chemotherapy. However, in Western medicine, we don't always do as good of a job recognizing when to stop those interventions or when those interventions might not be furthering the patient's quality of life.

People who have been through near-death experiences or have survived serious illnesses may use language such as "fighting" death or that they "beat" the disease. As providers, we need to be careful about the words we choose, because everyone is going to die. Dying isn't losing some kind of battle. For end-of-life patients who choose not to proceed with standard interventions or who choose alternative interventions, we need to be careful of giving the impression that they are perceived as not fighting or that they're giving up or losing. Those are important and difficult decisions for every patient to make. The language that we use can make an impact on patients. If we are truly being patient-centered, we need to use language that respects the choices of our patients.

Fantasy Death Exercise

Now, I'd like to conduct an exercise. Take a moment to imagine the most wonderful death you can think of for yourself. It doesn't have to be realistic. It can be fantastical. It can be whatever you want. This may be a difficult exercise for you, and that's okay. I'll give you some things to think about:

- Where are you located?

- Who is with you?

- What are you doing?

- Are there any physical or emotional symptoms that you're feeling?

- How long have you known?

Some common themes and ideas that we see across cultures include wanting to:

- Feel at home, or be at home in a beloved place (e.g., a beach)

- Be comfortable; in their own bed

- Have a sense of completion; accomplishment of life tasks

- Have a chance to say goodbyes; tell people you love them

- Review and reflect on their life

- Feel loved and spiritually cared for

- Be without pain

- Not have a prolonged or drawn out death; die in their sleep

The purpose of this exercise is to draw attention to the mismatch between people's fantasy death scenarios as compared to what really happens in the United States. I think that's one of the areas where, as rehabilitation services individuals and therapists, we can help bridge that gap for people.

Research and Statistics

In 1995, the Journal of American Medicine Association published a support study that looked at a large sampling of people at the end of their life. The title of this publication was "A Controlled Trial to Improve Care for Seriously III Hospitalized Patients: The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT)" (Connors et al., 1995). The objective of the study was to improve end-of-life decision making and reduce the frequency of a mechanically supported, painful and prolonged process of dying. It was a two-year prospective observational study (Phase I) with 4301 patients, followed by a two-year controlled clinical trial (Phase II) with 4804 patients. In total, they studied 9105 adults (hospitalized across five teaching hospitals in the United States) with one or more of nine life-threatening diagnoses, with an overall six-month mortality rate of 47%.

Link to article (copy and paste into browser): https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/391724

Overall, in the case of 53% of these subjects, there was confusion on the part of physicians who did not understand that a patient wanted to avoid CPR. I think we could all agree that receiving CPR is probably not going to be comfortable or peaceful, nor is it a situation where you necessarily feel loved. It's very disruptive, and in the last days of a person's life, it is understandable that someone would want to refuse CPR.

Unfortunately, according to this study, many people endured prolonged suffering at the end of their life. They found that 38% of these subjects spent 10 or more days in the ICU, in a coma, or on a ventilator. Furthermore, they found that 50% of these subjects experienced moderate or severe pain at least half of the time within the last few days of their life. In looking at these statistics, does it appear that sufficient pain control was implemented? Have we taken measures to ensure that people are not experiencing this kind of suffering at the end of their life? I would presume that when choosing your perfect death, none of you would choose to spend your last days in misery and anguish. Again, this is not a desirable outcome for a dying person to experience pain and discomfort to this degree.

SNF Pain Data (2001)

In 2001, the Journal of American Medical Association published some data about the rate of persistent pain in United States skilled nursing facilities. As reported in JAMA, 41.4% of patients at the end of their life reported worsening pain or pain that remained at a severe level. Reports of persistent severe pain were a little bit higher, at 46.7%. Terminally ill patients reported pain at a rate of 44.3%, and 48.3% of nursing home residents complained of persistent pain. Clearly, there is a gap that can be narrowed with regard to patients' pain.

Impact on Families

Unfortunately, when we look at some of these studies, we can see that serious illness has many negative impacts on the patient's family members (SUPPORT: Phase I, JAMA, 1994). People in this study who had a seriously ill family member reported the following:

- Needing a large amount of family caregiving: 34%

- Losing most of the family savings: 31%

- Losing their major source of income: 29%

- A major life change for a family member: 20%

- Other family illness from stress: 12%

- At least one of the above: 55%

Over half of the people in this study listed at least one of these occurrences as a major complaint. When we're working with a patient at the end of their life, we're also going to be heavily involved with the patient's family. As therapy professionals, some of the services we provide can be helpful to the family members who will continue living.

Site of Death

When you pictured your fantasy death scenario, where did you envision yourself? Unfortunately, patient preferences seem to be irrelevant when we look at predicting where someone dies. More relevant predicting factors include how many hospital beds are there in that city? How much do they spend on hospice? What percent of people go to nursing homes? How much is spent on long-term care? What is the patient's particular diagnosis?

On a personal note, when my mother was very ill and at the end of her life, she said she didn't want to come live with me because she didn't want to be in my house when she died. Instead, she preferred to be someplace like a nursing home or a skilled nursing facility. In some cases, a person is too ill to make that decision for themselves. However, if a terminally ill person has the presence of mind to choose a long-term care or skilled nursing facility as the location they want to live out the remainder of their life, they have actively thought about that decision and we need to take that seriously.

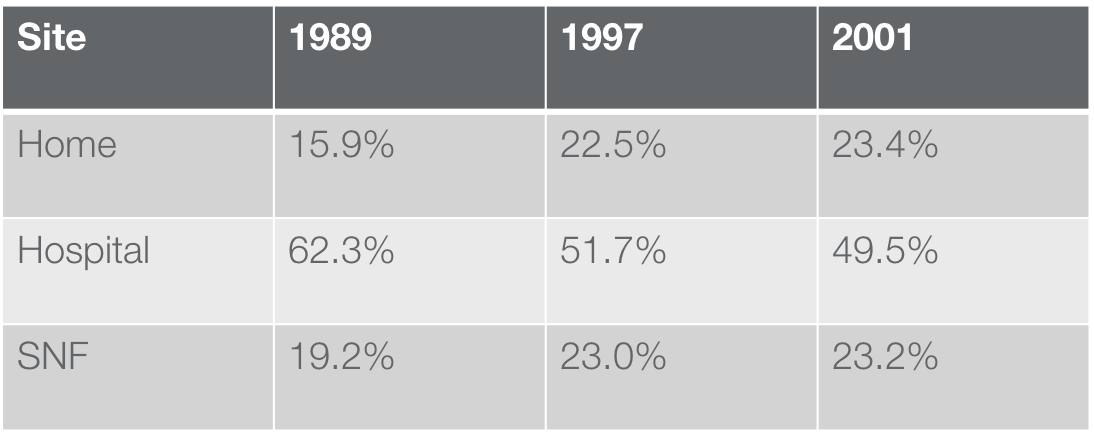

Looking at the sites of death trends in the United States between 1989 and 2001, according to the Center on Gerontology and Health Care Research, more people are dying at home and fewer people are dying in hospitals (Figure 1). Deaths in skilled nursing facilities are increasing, but that might be related to patients who are already living in a skilled nursing facility. Additionally, if a person can't stay at home alone, and if they don't have a spouse or a family member to live with, they might need to go to a SNF for that end of life care.

Figure 1. The site of death: US adjusted rate.

This data is available at http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm

Length of Stay Differences (2010)

Let's look at some Medicare data comparing site of death trends in relation to the length of stay. In 2010, inpatients who died in the hospital stayed an average of 7.9 days, compared to an average of 4.8 days for all hospital inpatients. Although 45% of people who died in the hospital stayed from one to three days, 57% of all inpatients had stays that were this short. Over one-quarter of the patients who died in the hospital stayed 10 days or more, compared with 10% of all hospitalized patients. Additionally, one-quarter of patients who died in the hospital were aged 85 or older. It is worth noting that hospital death rates did decline from 2000 to 2010 for diagnoses with high death rates, except for septicemia, which increased. This is why hospitals are so concerned about sepsis. In summary, patients who died in the hospital had longer average hospital stays than all patients (CDC/NCHS, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 2000-2010).

It is critical that we find a way to prevent a person from dying in the hospital setting if those are their wishes. Furthermore, if a person wants to avoid extreme measures and technologically intense care at the end of their life, we need to do everything we can to comply with their request. Ultimately, the wishes of the patient should be driving the conversation. That being said, we do also need to recognize that a lot of health care dollars and resources are spent on patients in hospitals who are, unfortunately, passing away. Although money is not the primary argument, it is an additional caveat to consider. The main concern should be focused on preventing people from dying in the hospital. As evidenced by our fantasy death scene exercise, most people do not indicate that they desire to die in the hospital. How can we, as rehabilitation healthcare providers, play a part in helping end-of-life patients fulfill their fantasy death scene?

End of Life Care

At the end of life, a person can receive care that is considered "technologically intense". For example, when a person is in the ICU, they may undergo a lot of medical interventions, such as being intubated, having various surgical procedures, receiving advanced drugs and other measures to keep them alive.

Recent research has shown that technologically intense end of life care is less likely in the following cases/situations:

- In Whites

- In North America and Northern Europe

- If your physician shares your geo-ethnic background

- If your physician has more clinical experience

- If your physician routinely works in ICU

It's not just about who you are; it's also about your care provider, your ethnic background and where you live that determines whether you receive less of this type of intense care (Frost et al., 2011).

Conversely, the Frost research team also found a correlation that technologically intense end of life care is more likely in the following cases/situations:

- In younger populations

- In those with fewer comorbid conditions (healthier people)

- In those with good (not limited) functional status

- In males

When we think about it, if a healthy 20-year-old has experienced some kind of trauma or accident, we're likely going to throw a lot of care at that individual because we believe that their prognosis is better. Unfortunately, there are many people with poor prognoses who are still receiving these technologically intense interventions. We need to do a better job of being more attuned to end of life care scenarios.