Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Treating Sleep Deficits In Individuals With Neurological Impairment Utilizing Occupation-Based Sleep Interventions, presented by Yvonne Monti, OTD, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine the incidence of sleep deficits in the population with neurological impairment.

- Evaluate occupational therapy's role in sleep management.

- Apply evidence-based occupational-based assessment and interventions for sleep.

Introduction

Hello everyone. I am glad to be here to talk about sleep. W.C. Fields has got it all figured out. He says, "The best cure for insomnia is to get a lot of sleep." Well, if only it were that easy. Hopefully, this presentation is not a cure for your insomnia. I will try my best not to put you to sleep, but if I do, maybe you can play this for your patients and see if they can catch a few ZZZs. All kidding aside, let's start talking about sleep and the incidence with neurological populations.

Sleep and Neurological Injury

- 50% have problems with sleep following brain injury

- 70% experience fatigue (Theadom et al., 2016)

- Up to 57% of people with stroke meet the criteria for insomnia (Glozier et al., 2017)

Dysfunctional sleep is one of the most common complaints among the neurologically impaired population. Half of all those who sustain an injury to the brain report sleep problems, with 70% experiencing daytime fatigue. That is a lot. Post-traumatic insomnia is the most common sleep disorder following brain injury, with an incidence of up to 65% for individuals who sustain a TBI and 57% of those who survive a stroke. Sleep problems frequently occur as well as fatigue.

Parkinson's Disease and Multiple Sclerosis

- 64% of those with PD report sleep disorders

- High prevalence of insomnia with MS and PD

- Fatigue is common; more than half of PD patients

- Fatigue and daytime sleepiness are common symptoms of MS, 53–92%

- Up to 60% of MS patients report fatigue most disabling symptom

(Fink, Bronas, & Calik, 2018)

Parkinson's disease and MS have high incidences of sleep problems, with 64% of those with Parkinson's and 60% of those with MS reporting a sleep disorder. Insomnia is one of the most commonly reported sleep disorders, as is fatigue and daytime sleepiness. More than half of those with Parkinson's and 53 to 92% of MS patients report interfering fatigue. Sixty percent of persons with MS report fatigue as the most disabling condition related to their disease. We, as occupational therapists, already know this and do things like energy conservation for fatigue-related conditions associated with MS all the time. But, have you considered addressing sleep and seeing how well the patient is sleeping?

Sleep and Neurological Injury, Cont.

- Sleep deficits affect rate and extent of recovery

- May occur immediately after brain injury or develop later in recovery

- Sleep/wake cycles susceptible to disruption

- Daytime arousal levels decreased (Wickwire et al., 2016)

- Sleep deficits negatively impact daytime function

Sleep deficits may present acutely or develop later in the recovery process. The presence of sleep dysfunction is linked to poor recovery rates, morbidity, and long-term disability. Sleep and wake cycles are susceptible to disruption by any injury or disease that affects brain function. Lack of sufficient nighttime sleep can lead to daytime fatigue and decreased arousal levels. Daytime fatigue may contribute to increased napping and negatively impact participation and performance in daytime occupations. So this interesting study that I came across stated that sleep is directly associated with motor recovery following stroke. Research supports that sleep deficits following an infarct have been proven to slow motor recovery of the individual.

Sleep and Motor Recovery Post Stroke

- Sleep deficits slow motor recovery

- Motor skill learning is enhanced by sleep

- More time in REM is associated with motor learning

- Balance is negatively influenced by sleep deficits (Kyung-Lim et al., 2017)

- Need to screen for sleep issues to enhance recovery

(Siengsukon et al., 2015)

Evidence supports that motor skill learning is enhanced by sufficient sleep and correlated more closely with the time spent in REM or rapid eye movement sleep. The evidence supports the importance of identifying and treating sleep issues early after an injury to the brain. Improving sleep in acute stroke patients can lead to better motor recovery outcomes and enhanced occupational performance and participation. It is also essential to know and keep in mind that sleep deficits are correlated with deficits in balance, which can place an individual at increased risk for falls.

In these two studies, one showed that patients need sufficient sleep to regain their motor skills, and the other showed that sleep negatively influences balance. These two factors are important to remember when addressing sleep in individuals recovering from neurological injury and who may already have deficits in balance, safety issues, or high fall risk.

Diagnosing Sleep Issues

- About 6% of stroke survivors offered formal sleep testing

- Only 2% complete testing first 3 months poststroke

- Physicians do not ask; patients do not report

- Need for early identification for high-risk individuals

- Need for OT to include sleep screening

- Can benefit those with chronic deficits

(Siengsukon et al., 2015)

Despite a greater incidence (more than 50%) of having sleep disorders after a stroke, only about 6% of stroke survivors are offered formal sleep testing, with an estimated only 2% of those completing testing three months post-stroke. Sleep problems are not being addressed adequately in doctor's offices. Physicians are not asking about sleep, and clients are not offering up sleep complaints without a cue from their doctor. Identification of sleep issues in high-risk individuals is imperative to their health.

This is where we come in. Occupational therapy can be essential in screening, evaluating, and even treating sleep problems in this population. While early intervention is necessary, as we discovered that sleep is directly linked to motor recovery, it is also essential to identify and address the issues in those with chronic injury or disease. These are clients we have been seeing on and off for years. Are we asking our clients if and how sleep affects their participation in occupations?

Common Sleep Deficits

- Difficulty with:

- Initiating sleep

- Maintaining sleep

- Sleep quality

- Daytime sleepiness

- Hypersomnolence

- Increased napping

- Sleep quantity

Individuals may report difficulty getting to sleep or the initiation of sleep. They may say lying in bed for up to three or four hours before falling asleep. Some of you can relate to this if you have sleep issues. Interrupted sleep or difficulty maintaining sleep may be other issues. Clients may report waking up several times a night or waking up and then not being able to get back to sleep.

After an injury to the brain, individuals may report that they sleep all night, but they never feel rested, and their quality of sleep is diminished. If I hear an issue like this, I often think that there may be something else going on. They may have sleep apnea or something that needs to be diagnosed.

Daytime sleepiness and increased napping can result in neurological problems. Hypersomnolence or sleeping too much may interfere with occupational performance. If the patient has hypersomnolence immediately following an injury to the brain, this can signal that the brain is still healing. So there are times when we want to let our clients have a little extra sleep.

We may have to work on the schedule in an acute setting. Do we let the patients sleep when they can, or do we get them on a regular schedule? Do we interrupt that nap to give them therapy? Productivity and our schedule can impact this, and we may need to look back at how the patient is recovering.

Hypersomnolence is also linked to mood disorders. Clients with mood disorders may have difficulty regulating sleep patterns, with some reporting getting two or three hours of sleep at night.

Other Contributing Factors

- Pain

- Mood

- Lifestyle changes

- Medication side effects

- PTSD

- Illicit drug or alcohol use

Several other co-occurring conditions may contribute to sleep problems. The first one is pain, as it is prevalent in individuals with neurological disorders. It could be shoulder pain where they cannot get comfortable as they are going to sleep. They could have headaches or pain in their legs, hips, or back. Pain can interfere with sleep and make initiating and sustaining sleep difficult. Pain may be something that we have to address but in a different way than what I am going to be talking about today.

As mentioned, mood changes can affect sleep. Depression and anxiety also commonly occur in this population. They could be either something that is a co-occurring condition or new following the injury. Depression can lead to hypersomnolence, while anxiety can lead to increased worry and intrusive thoughts while trying to fall or stay asleep. You cannot shut your brain off. I am sure we have all experienced where you cannot turn your brain off at night. These individuals may be experiencing this a little bit more.

Lifestyle changes can affect sleep, like decreased physical activity and changes in their routines. Some people might have experienced this during the COVID shutdown with significant changes to our routines and habits. Some of my students said they slept all day and were up at night because they had no schedule to hold them accountable.

New or worsening PTSD may also contribute to insomnia, poor sleep, and nightmares. Many interventions I will discuss today have been proven to work with individuals with PTSD.

Many patients are on many medications, and these side effects can cause insomnia, vivid dreams, and daytime drowsiness, like baclofen or anti-seizure medication.

We also want to screen for illicit drug use or alcohol, as both can affect our sleep patterns.

Pain, mood, lifestyle changes, medication side effects, PTSD, and drug and alcohol use can all interfere with sleep. It can become a vicious cycle of insomnia, especially with our patients with neurological injuries. You can ask them, "I know that you can't sleep, but did you know that lying in bed and not sleeping can also increase your back and shoulder pain and affect your mood and anxiety?" Finding a way to address these will help improve sleep and support a return to prior occupations.

Secondary Deficits Relating to Sleep Problems

- Longer rehabilitation stays

- Poor community reintegration

- Increased cognitive impairments

- Decreased work performance

- Decreased school performance

- Diminished balance

- Decreased quality of life

Difficulty sleeping has contributed to more extended rehabilitation stays for individuals with neurological diagnoses. It would be beneficial if we could work on decreasing the number of days this patient stays in the hospital.

An increased need for rest can limit social participation and lead to social isolation for many of these individuals. They may lose social connections, which can contribute to loneliness.

Working concentration, attention, and new learning are directly impacted by fatigue and a lack of sleep. New cognitive impairments and fatigue contribute to deficits in participation and work and school performance. They may be able to go to work or school, but then they cannot pay attention or participate. And they may not be safe on the job because they are so exhausted.

Decreased quality of life can be directly linked to sleep problems in this population. Thirty percent of individuals who suffer from brain injury are diagnosed with a clinical sleep disorder. This percentage is most likely skewed based on the low referrals for testing. Of that 6% that get tested, 30% are diagnosed with a sleep disorder. So, we know that this number is probably a lot higher.

Unfortunately, many sleep order symptoms overlap other conditions linked to brain injury, which is often unaddressed by physicians and therapists. Sleep specialists diagnose sleep disorders following extensive sleep assessments in the sleep clinic. However, OTs can also help screen and make referrals if needed.

Common Clinical Sleep Disorders

- Insomnia

- Circadian rhythm disorders

- Narcolepsy

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- REM sleep disorder

- Restless legs syndrome

- Periodic limb movement

Some of these disorders are insomnia, Circadian rhythm disorders where days and nights are flipped, narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, REM sleep disorders, restless leg syndrome, and periodic leg movement.

Post-Traumatic Insomnia

- Persistent difficulty with:

- Sleep initiation

- Sleep duration

- Sleep quality

- *Occurring even though there is an opportunity for sleep*

- Daytime impairment:

- Fatigue

- Mood issues

- Irritability

- Malaise

- Cognitive impairment

(Hepburn et al., 2018)

Post-traumatic insomnia (up to 65%) is the most common sleep disorder following a brain injury. Evidence-based interventions I will discuss have been designed to remediate or modify specific dysfunctional components that lead to insomnia.

Symptoms of insomnia are falling asleep, sleep initiation, staying asleep, sleep duration, sleep quality, and how well somebody sleeps. There is also the daytime impairment component that includes fatigue and sleepiness. Fatigue and sleepiness are a little bit different from each other. Fatigue is when someone might say "I am tired, but no matter what I do, I still cannot take a nap or fall asleep". Sleepiness is when a person might experience "as soon as I sit down, I fall asleep".

People with insomnia have a hard time napping. They have mood issues, irritability, malaise, and cognitive impairments. Insomnia occurs even though there is the opportunity and circumstances for sleep and there are perfect conditions in their home. We are talking about post-traumatic insomnia because some of these patients were great sleepers before this happened, and now they cannot.

Occupational Therapy's Role in Sleep Management

Let's shift gears a little bit. We talked about the incidence of sleep disorders. I hope I have convinced you that this is important to address with our patients. We are not talking about it enough with them, which contributes to a decreased quality of life and the participation and performance of occupations.

- Sleep and rest are core occupations in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework

- Sleep disturbances can negatively impact occupations

- The promotion of good sleep can increase well-being, quality of life, and health

What is our role in sleep management? Sleep and rest are core occupations in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework. Sleep disturbances are directly influenced and negatively impact other meaningful occupations, affecting performance and participation. The promotion of good sleep can increase well-being. Think about what it feels like after a great night's sleep. You feel like you are ready to take on the world. Think about being up all night, having a horrible night's sleep, and then driving 18 hours. Your performance is going to be affected by that poor night's sleep.

Occupational Performance and Sleep

- Sleep directly influences performance and participation in occupations

- The occupation of sleep includes:

- Rest

- Sleep preparation

- Sleep participation

(American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020)

Rest and sleep are activities related to obtaining restorative rest and sleep to support healthy, active engagement and occupations. Occupation-based sleep management should focus on the transactional relationship between the person, their environment, and occupation with the intended outcome of improving rest and sleep.

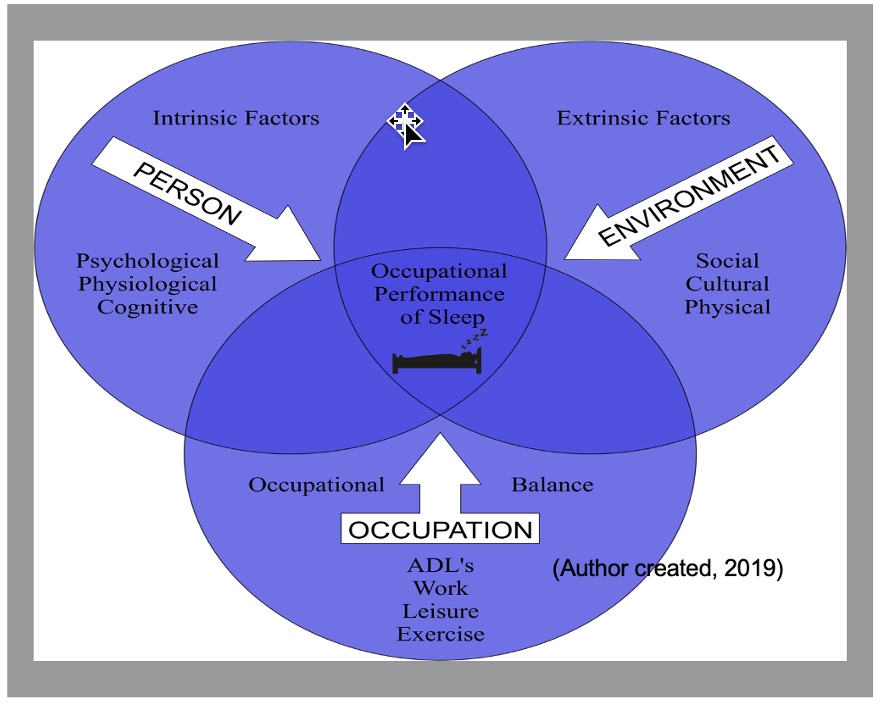

PEOP Theoretical Model of Sleep

- Person- psychological, physiological, cognitive

- Environment- social, cultural, physical

- Occupation- ADLs, work, leisure, social participation

- Occupational Performance- Sleep

The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model can assist with decision-making and critical reasoning to address client-specific performance problems related to sleep.

We can also use the Cognitive-Behavioral Frame of Reference for sleep management. This supports the use of techniques to help individuals self-manage thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that influence sleep while also addressing environmental problems, contributing to maladjusted thoughts or behaviors.

The components that we will be addressing are person components, which are psychological, physiological, and cognitive; environmental components, which focus on promoting a conducive sleep environment and eliminating or modifying aspects of the social, cultural, or physical environment; and occupations that may influence sleep. Figure 1 shows the PEOP model.

Figure 1. PEOP model with sleep factors.

The occupational components should look at restructuring daytime activities and achieving occupational balance. Deficits in all three areas must be remedied for the successful occupational performance of sleep.

Cognitive-Behavioral Framework

- OTs assess environment, cognition, and behavior

- Deficits= dysfunctional thoughts and maladaptive behaviors

- Remove barriers= occupational performance improves

- Many OT interventions/techniques originate from CBT

- OT distortive thinking interventions: relaxation techniques, visualization, thought stopping, self-instruction

(Cole & Tuffano, 2020)

The Cognitive-Behavioral Framework guides the occupational therapist in identifying internal and external characteristics of the individual that may contribute to inappropriate sleep behaviors. It also looks at the individual's internal thoughts, maladaptive behaviors, environmental factors, behavior modification techniques, environmental modifications, and interventions to eliminate distortive thinking, remove barriers, and improve the occupational performance of sleep. Many OT interventions originate from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), including things we already do like relaxation techniques, visualization, thought stopping, and self-instruction. These techniques can all be utilized for the occupation-based management of sleep.

Assessment

Now let's talk about assessment. I quickly went through much of the background information to spend more time on assessment and intervention.

Sleep Assessment

- Gather demographics

- Complete occupational profile

- Including psychological factors (depression, anxiety, and PTSD)

- Screen for sleep disorders and pain interfering with sleep

When assessing an individual's sleep, we will gather demographics like we always do. We will complete an occupational profile and look at any psychological factors, particularly depression, anxiety, and PTSD because we know how they can negatively influence sleep. We will also screen for sleep disorders and pain interfering with sleep.

- Complete standardized assessments

- Assess lifestyle factors that contribute to decreased sleep

- Assess sleep environment

- Assess for occupations affected by sleep deficits

- Assess for cognitive and behavioral factors contributing to sleep deficits

We can use standardized assessments as part of our formal assessment. We want to assess lifestyle factors contributing to decreased sleep and their sleep environment. Where do they sleep? Do they sleep in a chair or bed? Do they have sleep partners or animals in their beds? Is it cool? Is it dark? What is the sleep environment? We want to assess for occupations affected by sleep deficits. Finally, we want to assess cognitive and behavioral factors contributing to sleep deficits.

Standardized Assessments

- Insomnia Severity Index

- Sleep Disorders Survey

- Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- Fatigue Severity Scale

- Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- The Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

This is not an inclusive list, as I am sure there are other standardized assessments out there. These are the ones that I have used that are valid and reliable.

Insomnia Severity Index

The first is the Insomnia Severity Scale, a self-reported questionnaire that establishes insomnia severity. This can be used before and post-intervention to see if your intervention decreased insomnia.

Sleep Disorders Questionnaire

The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire can be utilized as a screening tool for insomnia and other sleep disorders. This one is great because you may be able to address other issues other than insomnia, like sleep apnea.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale/Fatigue Severity Scale

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale and the Fatigue Severity Scale can help identify the severity of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or both.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index is one of my favorite tools because it can be used to look at sleep quality, latency, duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, and the use of sleeping medications, as well as daytime dysfunction. It also can be used as a screening tool because there is a section that asks questions about things like snoring, abnormal limb movements, and confusion at night. And it allows the spouse to chime in because that gives us more information. Many of us do not know that we snore until our spouse tells us, and sometimes we do not believe them. They may also be able to provide information like if we keep them awake by kicking and rolling all night.

The Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire

The Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire is a good tool because we can identify occupational performance deficits related to sleep dysfunction. When writing our goals, you may wonder how to treat, code, and bill for sleep treatment.

Sleep is one of our occupations so we can write a goal about that, but it also affects other ADLs and IADLs. We can bill for an ADL or therapeutic activity.

Consensus Sleep Diary

- Standardized assessment- guides treatment

- Sleep onset latency- how long it takes to get to sleep

- Number of nighttime awakenings

- Sleep efficiency – the percentage of time asleep when in bed

- Total daily sleep time- including naps

- Sleep Quality

The Consensus Sleep Diary is the tool that I want you to remember. It is a standardized assessment, and you will use it in your initial assessment. The client completes it for about two weeks, if not longer, and then brings it back so we can devise an intervention. It is completed daily in the morning to document the previous night's sleep. There are short and long forms based on what information you want to gather on your client.

The long form has more information on things like the consumption of caffeine or alcohol and bedtime and wake times. It also looks at sleep onset latency, the number of nighttime awakenings, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and sleep quality.

The daily scoring of the diary can validate progress, and intervention is guided based on the logs you collect. This tool should always be used as an assessment and part of your intervention. I recommend you fill it out yourself so you can get used to it. The nice thing about that diary is that it has an instruction form where you can sit down and review how to fill it out. It should not take more than two or three minutes to fill out. It has been found to have good compliance.

Intervention

OT Sleep Intervention Focus

- The use of a multi-component intervention is most beneficial (Edinger et al., 2021)

- Treatments should include both person, environment, and occupation components (PEOP) (Ho & Siu, 2018)

- Cognitive and behavioral interventions improve sleep (Edinger et al., 2021)

- Sleep interventions should be provided early and throughout the continuum (Theadom et al., 2016)

I compiled all the data research and found that using a multi-component treatment is most beneficial. This is using several components to treat sleep versus a single component. We already talked about how treatments should include the person, environment, and occupation and both cognitive and behavioral interventions improve sleep. An example is CBT-I for insomnia, as it treats both the cognitive and behavioral aspects of sleep.

We also learned that sleep intervention should be provided early and throughout the continuum of the recovery process, as sleep problems can affect the individual's recovery and contribute to the length of hospital stays.

Sleep Hygiene

- Sleep hygiene is beneficial in improving sleep ONLY when used with other measures

- Should not be used as a single component

(Edinger et al., 2021)

For years, we have been told that sleep hygiene is how occupational therapists treat sleep. We look at the sleep environment, and I will briefly discuss these components. When researching how to treat sleep best, I thought I would find out a lot about sleep hygiene, but what I found was pretty surprising. Sleep hygiene is only beneficial in improving sleep when it is combined with other methods. It should not be used as a sole component for intervention. It is a valuable component of a multi-component design.

- Limit screen time prior to bed

- Ensure dark sleep environment

- Ensure cool sleep environment

- Limit alcohol consumption

- Limit disruptive sleep partners, including pets

- Establish bedtime routine

- Limit caffeine prior to bed

- Don't eat to close to bedtime

Here are the components of sleep hygiene that clients may know pretty well. However, you might need to review them again and edit how things are happening. First, we know that limiting screen time before bed is essential. The sleep environment needs to be dark, cool, and quiet. Clients should limit caffeine and alcohol consumption before bed as it interrupts circadian rhythm. Disruptive sleep partners also need to be modified if able. Older clients often report sleeping in different rooms because their sleep partner snores or pets can interfere with sleep. If people are unwilling to not sleep with their pets, we may have to devise different ways for them to get restful sleep. Other ideas include establishing a bedtime routine as part of sleep hygiene and not eating too close to bedtime. These are many things our clients already know, but you will be able to pick up on issues with the Consensus Sleep Diary.

Occupation-Based Interventions

- Review lifestyle changes that can be made

- Educate patient on the effect of daytime occupations or lack of occupations on sleep

- Devise a plan with the patient to develop occupational balance

- As sleep improves and fatigue decreases, encourage a return to normal routines

Many individuals with neurological impairments suffer from drastic changes to their lifestyle, roles, and routines. Sleep deficits and fatigue can further contribute to occupational dysfunction. We can make recommendations on how to incorporate lifestyle changes to improve sleep. For example, if an individual may not feel tired at night because they were sedentary all day, they may want to add some exercise to promote improved sleep or give them a schedule. The opposite may occur if increased activity contributes to fatigue, requiring the need for a nap. For example, your client may go to the grocery store and then be wiped out for the entire day. We must help them create an occupational balance by adding meaningful activities or scaling everything back. Then, you can slowly reintroduce these activities when the occupational balance has been achieved. We will also be talking about energy conservation for some of these individuals. We are already doing that as occupational therapists, but it can be part of our sleep intervention and a multi-component design.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

Combination of one or more of:

- Cognitive refocusing

- Sleep regulation

- Stimulus control

- Sleep restriction therapy

- Sleep hygiene education

- Relaxation training

(Edinger et al., 2021)

Let's talk about cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). CBT-I combines one or more of these cognitive therapy strategies with education about sleep regulation plus stimulus control, instructions, and sleep restriction therapy. CBT-I includes sleep hygiene education, relaxation training, and other hypoarousal methods to help them relax. CBT-I is heavily researched and is the most effective intervention for insomnia. Is this something you can go out and do tomorrow? Probably not all, as there are components you would need to get further training to successfully apply the intervention, especially with the neurological population where it can be a little riskier.

There are pieces of this that you can start using. I highly recommend you get more training to further your knowledge on applying this therapy to individuals. With that said, I think occupational therapists are an excellent fit for CBT-I.

- Assessment and treatment data gathered by sleep diary

- Diary completed throughout the treatment

- Treatment ranges from 4–8 sessions

- CBT-I may reduce the need for sleep medication

- Educate on normal sleep variances

(Edinger et al., 2021)

Treatment is established using information typically gathered with a sleep diary, like the Consensus Sleep Diary, completed by the patient throughout treatment. It is typically four to eight sessions and may reduce the need for sleep medications, which is fantastic. Education on normal sleep is also an important component. What feels good to do- seven, eight, nine, or 10? Eight is not the magic number and not appropriate for everybody. It is also essential to let people know that it is normal to wake up two to three times a night, but you should be able to go back to sleep after this. Instruction on circadian rhythm and sleep stages is also helpful for individuals.

- Daytime sleepiness, mood impairment, and cognitive difficulties may increase initially with behavioral therapy.

- Negative symptoms improve as sleep improves, usually resolving at the treatment's end (Edinger et al., 2021)

- Contraindications include: bipolar disorder, epilepsy, the risk for falls, panic disorders, and obstructive sleep apnea

- No certification for CBTi; however, recommend continued education and mentorship

It is important to educate clients on daytime sleepiness, mood impairments, and cognitive difficulties that may increase when we initiate the behavioral component. However, as sleep improves, these symptoms will decrease. They also should not operate their car or heavy machinery. Contraindications for this treatment are bipolar disorder, epilepsy, risk of falls, panic disorders, and obstructive sleep apnea. No certification is required to complete CBT-I, but I highly recommend continued education and mentorship.

Behavioral Interventions

Let's now talk about some of the behavioral interventions.

Sleep Restriction Therapy

- Utilize a sleep diary to determine total sleep duration (2 weeks)

- Modify approach as needed

- Do not use with persons with a seizure disorder

(Edinger et al., 2021)

The first is sleep restriction therapy. It is a great tool that helps individuals. Sleep restriction is a method designed to improve sleep by limiting the time spent in bed. Sleep restriction should be client-centered and modified for each client based on the severity of neurological issues. Sleep restriction should not be used with clients with seizure disorders or other contraindications.

- Restricting time in bed to match client's total sleep duration (2-week sleep diary)

- No less than 4.5 hours in bed

- As sleep efficiency improves, time in bed is increased until core sleep requirement is met.

- Set strict bedtimes and wake times

(Edinger et al., 2021)

To establish sleep efficiency, the patient's total sleep duration is divided by the time spent in bed. Sleep duration is estimated based on 10 to 14 days of their sleep diary. If their sleep efficiency is 80%, they get about four and a half hours of sleep but stay in bed for an hour longer. You are then going to limit the time they are allowed in bed to only 4.5 hours, and we are not going to go less than that. You establish new strict bedtimes for this individual. If they go to bed at midnight, they need to get up at 4:30 in the morning. They will maintain that for a week. If they start sleeping better, they can increase their time allowed in bed.

- Sleep time is increased by 15-30 minutes

- No napping allowed

- No clock watching

You can increase it by 15 minutes to 30 minutes, based on if you are doing sleep restriction therapy or sleep compression. You are not going to allow napping or clock watching. "It's 1:00, 1:15, 1:30. and I'm still not sleeping."

Stimulus Control

- Goal is to eliminate the association between the bed and wakefulness

- Instructions:

- Go to bed when tired

- Get out of bed if unable to sleep (20 minutes)

- Bed only for sleep and sex

- Wake up same time every day

- No daytime napping

(Edinger et al., 2021)

Another component is stimulus control. It is designed to eliminate the association between the bed and wakefulness. If the patient is rolling around in the bed and not sleeping, they will start associating that bed with not sleeping. They are only to go to bed only when they are tired. If they cannot sleep after 20 minutes, they are to get out of bed and not return until they start to feel sleepy. They are not going to do anything exciting or thought-provoking. Instead, they will do something quiet and restful, and OTs can help them figure out what that is. These rules are posted on the bed. The bed should be only for sleep and sex, not tv watching or homework. Another stimulus control principle is that individuals should wake up and go to bed at the same time every day. Again, there is no daytime napping.

Relaxation Therapy

- Techniques to decrease tension of mind and body and cognitive arousal/intrusive thoughts that interfere with sleep

- Recommend to be used as part of a multi-component design

- Techniques:

- Abdominal breathing

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Guided imagery

- Meditation

(Edinger et al., 2021)

Relaxation techniques decrease tension of the mind and the body to decrease cognitive arousal and intrusive thoughts. We recommend that they use this as part of the multi-component design. Techniques include abdominal breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and meditation. There are also many apps and YouTube videos. You can even give them recordings of yourself.

Client-Centered Sleep OT

Should also discuss habits, routines, and rituals revolving around sleep

We want to make sure that our interventions are client-centered. We are going to modify and adjust sleep intervention based on the individual. Remember that there are cultural differences regarding sleep, like co-sleeping with children. Also, think about a college student's sleep pattern versus somebody older. We also want to discuss the habits, routines, and rituals revolving around sleep.

Cognitive Interventions

Let's talk about the cognitive interventions we will use for sleep as part of our multi-component design. Our goal is to decrease cognitive arousal with anxiety, worry, and intrusive thoughts that interfere with people's ability to fall asleep and stay asleep. We will also reduce the dysfunctional sleep beliefs that the individual may have, like "I'm not going to perform well tomorrow without a lot of sleep."

Cognitive Refocusing

- Decrease cognitive arousal

- Intrusive thoughts that interfere with sleep

- Decrease dysfunctional sleep beliefs

Cognitive refocusing has been done for years, and counting sheep is part of that. Instead of lying there worrying, the client will picture sheep jumping over a fence and counting them.

- Educate on intrusive thoughts and thought modification (can utilize mindfulness)

- Educate on the importance of using strategies to fall asleep both initially and if awoken at night

- Have the client choose 2-3 non-arousing thoughts that can maintain attention

Cognitive refocusing starts with identifying intrusive thoughts, anxiety, and worry that are stopping a person from being able to fall asleep. The client needs to be able to shift gears and stop thinking those thoughts. You and your client will come up with two to three non-arousing thoughts that can maintain their attention. They could talk through the lyrics of their favorite song, use guided imagery, prayer, or phonetic games, like ABCs with dog categories. For example, A is for Afghan, B is for Boxer, C is for Chow, et cetera. It is vital to shift the person from those intrusive thoughts into thinking about something else.

- Example: reciting favorite song lyrics, counting backward by seven from 100, meditation, prayer, mental imagery

- Pre-planned non-intrusive thoughts should be used initially to improve sleep onset and to return to sleep once awoken

- If not asleep in 20 minutes, get out of bed (stimulus control)

- Complete non-arousing activity until tired

As I said, lyrics, meditation, and prayer can be ideas. This is pre-planned, and they should have two to three options. If the first one is not working, they will shift gears to the second one. Then, they move into stimulus control if they are not asleep in 20 minutes. They must get out of bed and complete a non-arousing activity until they are tired. They then go back to bed and start over. These are techniques that you can apply tomorrow.

Anxiety, Worry, and Sleep

- Educate on progressive relaxation

- Educate on the influence of worrying on sleep

- Schedule a time to worry

- Educate on journaling to decrease worrying

- Educate on the use of organizational systems to decrease worry

- Gratitude

We are also going to educate our clients to decrease anxiety and worry. We can teach them progressive relaxation and educate them about how worrying is affecting their sleep. We may need to give them a time frame to worry. "You're allowed to worry, but it's from 4:00 to 5:00 and not right at bedtime." I know this seems silly, but it works. You can help them learn to keep a journal or use organizational systems to help them worry less and become more structured.

You can teach them about gratitude. If they are journaling, they can put all their worries in at the end but end with something about gratitude. They should focus on something positive before they go to bed to replace the negative thoughts. Gratitude is part of that multi-component design. Remember, if your intervention is not working, there may be another clinical sleep deficit.

Referral to Other Healthcare Members

- Primary care physician for pain management

- Sleep specialist for diagnosis of other suspected sleep disorders

If you suspect another clinical sleep deficit, refer them to their primary care physician or a sleep specialist. They may have pain or sleep apnea. A BiPAP or CPAP machine may help them breathe better for better sleep.

Next, I want to give you a couple of case examples so that you can think about how these interventions work.

Case Example- Case One

- 68 y/o man suffered a stroke one year ago

- Returning to OT to address UE limitations interfering with occupational performance and participation

- The patient reports deficits in participation and performance of sleep during the eval

- Reports decrease progress with motor relearning

- The OT completes the sleep assessment

Case one is a 68-year-old man who suffered a stroke one year ago. He returned to OT to address his upper extremity limitations interfering with occupational performance and participation. The patient reported sleep deficits and decreased progress with motor learning and relearning. A sleep assessment was completed.

- Patient's wife is present and reports that he:

- Snores loudly

- Takes long pauses between breaths

- Has difficulty with nighttime confusion

- She rates these- 3 or more times a week on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- Patient reports shoulder pain limits sleep

What did we do with this individual?

- The OT discusses the need for the patient to see primary care physician and possibly a sleep specialist to rule out a sleep disorder.

- Patient referred to primary care physician to assist in pain management of the shoulder

- Therapist will reassess after medical work up completed

- Therapist will address pain during the intervention as well as sleep positioning

It appeared the individual had some sleep apnea issues. He also had shoulder pain that interfered with sleep. We discussed the need for the patient to see his primary care physician and possibly a sleep specialist to rule out another sleep disorder. The patient was referred to his physician to ask if they could assist with pain management of the shoulder. The therapist addressed the pain and proper sleep positioning to help him get more comfortable during sleeping.

Case Example- Case Two

- A 21 y/o college student with mild traumatic brain injury 6 months ago

- Reports difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep

- Reports watching Netflix on phone in bed with dogs when can't sleep

- Reports ordering in groceries, not going to the gym, and having difficulty thinking, reading, and learning

- Scored a 21/28- moderate severity insomnia on the Insomnia Severity Scale

What did we do with this individual?

- Patient completes sleep diary for two weeks

- Week One:

- Data analyzed with patient

- Patient in bed 10 hours sleeping 5

- Sleep restriction for 5 hours

- Set strict bedtime and wake times

- Educated on stimulus control

- Educated on sleep hygiene

We gave him the Consensus Sleep Diary, had him fill it out for two weeks, and then analyzed the data. As the patient reported being in bed for 10 hours but only sleeping for five, we established sleep efficiency and restricted his sleep to only five hours in bed with a certain bedtime and wake time. We also educated him on stimulus control, encouraged him to leave the bed if he was not asleep in 20 minutes, and looked at sleep hygiene.

- Week Two:

- Sleep is improving- sleeping 5 hours 4/7 nights

- Reports still having difficulty with falling and staying asleep

- Instructed on cognitive refocusing techniques- initially and if awakened at night

- Educated on worry

- Agreed to journal for worry and gratitude

By week two, sleep improved, with them sleeping five hours four out of seven nights. He still had difficulty falling and staying asleep, so we instructed him on cognitive refocusing techniques and journaling for worry and gratitude.

- Week Three:

- Reports sleeping 5 hours 7/7 nights

- Increase time allowed in bed

- Adjust sleep times

- Discuss relaxation techniques

- Discuss bedtime routines

They slept five hours straight on week three, seven out of seven nights, so we increased the time in bed and adjusted sleep times. Relaxation techniques and a bedtime routine were discussed to help him relax before bed.

- Week Four:

- Reports sleeping 5.5 hours 7/7 nights

- Increase time allowed in bed

- Reset sleep times

- Encourage an increase in daytime activities

- Discuss plans for a return to learning

- Continue until the sleep goal achieved

By week four, they were sleeping an extra half hour, and his time in bed was increased. We reset the sleep times and encouraged an increase in daytime activities. As a result, he was now sleeping better and going grocery shopping. We discussed plans for returning to learning, returning to school, and continuing until the sleep goal was achieved. We intervened until he slept eight or nine hours a night and reported good sleep quality.

Summary

If you have any questions about this presentation, please email me. I would love to talk about sleep. We need more occupational therapists treating sleep in varied populations. Thanks for listening.

Questions and Answers

I read that napping was linked to high blood pressure and stroke. Do you know anything about this? How do we as OTs respond to the client if they ask about this?

Naps are controversial. Do we allow our client to nap? We have to sometimes not be so strict on some of our rules. We may need to allow for some safety naps, but not while we are doing sleep restrictions. For example, if we know they will be driving the next day, we can let them take that 30-minute nap. I consider naps on an individual basis. If patients are worried about their sleep time but taking frequent naps, I limit it. The nap can be 20 minutes or two hours. We add it to the total sleep time. They may say they sleep only five hours a night but take a two-hour nap. The total would be seven hours of sleep a day. They will need to start to shift this. I do not know the research on the link between napping and high blood pressure and stroke, but I do know that some people need those little naps throughout the day.

Do you think the connection between napping and cardiac issues could be related to a lack of mobility?

This is something that we talked about with lifestyle. Many individuals' lifestyles have changed where they are not as mobile. It is also an issue why they cannot sleep at night because they are not participating enough in daily activities to sleep. So many of our patients take naps, but if we keep them busy, can we get them through that nap period?

Do we know any screening or assessment tools for pediatric issues?

Many of the CBT-I techniques we discussed can be used for pediatrics. I would have to go back and look at the assessments. You can pull them up to see the age ranges, but I have done sleep interventions for teenagers. I have even tried techniques with my children because if they do not sleep, neither do I. I have used relaxation techniques and have a strict bedtime and wake time for them. They are on a good sleep schedule. So, yes, you can use many of these principles with pediatrics. I also know that those with autism have a lot of sleep issues. We would have to look up the literature on CBT-I for that population.

To clarify, sleep hygiene is only effective with other components. Is this true for all populations or those with neurological issues?

I would say this is true for all populations. In the literature that I looked up, it was with varied people. Sometimes insomnia was the only diagnosis. I found it very interesting that the clients had already tried sleep hygiene interventions. Again, sleep hygiene is an integral part of our intervention, but it cannot be the only intervention, or it will not work.

Is there any research that states sleeping in a recliner hindered sleep? Many of my patients sleep in a recliner at this age.

Some patients need to sleep in a recliner as they have GERD that interferes with sleep or some hidden sleep apnea. Nothing says you cannot get a good night's sleep in a recliner. I would probably let them try to stay in a recliner if you can do all the interventions.

Then, if they are still not sleeping, you may try shifting to a bed. Could you put the head of the bed on a block, so they are elevated a bit? It may be good to see their sleep environment. If they always were a good sleeper in that recliner and suddenly they are not, that tells us something.

How do I not clock watch, and get up in 20 minutes?

That is a good point. In the Consensus Sleep Diary, one of the instructions is, "Will this interfere with my sleep because I'm keeping track of how many minutes I'm sleeping?" So they need to have an estimate; it does not need to be exact. We may take the alarm clock out of the room. We all know that we have done that. "I've got a catch a flight. It's 8:00, 8:21, and now 8:31, and I'm still not sleeping." Clock watching can disturb sleep.

How effective is timely outdoor exercise, white noise, and a diary in those situations when the patient does nod off during the day?

I think it is important to include exercise or some activity as many clients have no schedule or organization for their day. They may have been very active or at least had a job and now have nothing. It is crucial to keep them busy and give them something to do throughout the day to help them keep from nodding off. We can also check their medications and talk to their physician.

Do you use fitness checks like Fitbit?

You can use a Fitbit to help monitor sleep. There are many options for this. I do not think the phone is accurate, but a wearable device is better.

Any intervention ideas for Parkinson's disease or restless leg syndrome?

You would use the same strategies we discussed if it is Parkinson's disease and insomnia. Heat may help those with restless leg syndrome. Taking a bath or shower before bed can help the body relax. You can also refer them to a physician for a diagnosis and medication.

Why is it unhealthy to sleep longer on the weekend when you don't sleep enough during the weekdays?

That is a great question. This is a topic that we need a whole other course to discuss. Sleeping late will disrupt your circadian rhythm. So if you sleep later during the day, your body will produce the necessary hormones later. Then, the next night's sleep will be affected. You will not feel tired when you need to go to bed to be up and ready for Monday. This is why people hate Mondays. They sleep on the weekends, and then they cannot get up Monday morning because they have shifted all the chemicals and hormones they need to sleep back a couple of hours.

There is no evidence showing that you can catch up on sleep. The only part of sleep that you can catch up on is REM. If you have not got enough REM sleep, your body will automatically put you into REM and catch you up that next night. So, you might have a night where you have not slept well and start dreaming the next night immediately. You shift everything with your biological and neurological systems regarding sleep when you sleep in, so it is crucial to keep that consistent. Good sleepers can do that shift and still go to bed and wake up. These are rules for insomniacs.

What are your low-budget recommendations for positioning in bed for patients with severe pain?

I will put the patient on a mat and find pillows and cushions. I love duct tape and cloth chuck pads or beach towels to make bolsters for them. You can put pillowcases over them for washing. Then, you can get them in a position where they are most comfortable. Again, we will want to talk to a physician about pain management.

When creating a sleep plan, how do you address different sleep patterns between spouses?

That can be a challenge. If their spouse is interfering with sleep or they come to bed later, we may need to devise a plan and reintroduce co-sharing of the bed.

Have you found if referring doctors are aware of OTs addressing sleep? Can someone be referred for sleep issues only without a physician referral?

This is the question I was hoping to get. We are not a "go-to" yet for referrals. Usually, I address that with the patients I am already treating for neurological injuries (strokes, MS, concussions). Physicians refer them to me, knowing that this is something that I address. I write occupation-based goals for return to work or school and increasing other activities. For example, "They will sleep so many hours to be able to participate in grocery shopping or XYZ."

You will have to look at state licensing and see what is included in OT to see if you are covered. Workers Comp does not find this beneficial yet, but I hope recent research can change that as it is one of our core occupations. We should be treating sleep.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74 (Supplement 2). 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Baylan, S., Griffiths, S., Grant, N., Broomfield, N. M., Evans, J. J., & Gardani, M. (2020). Incidence and prevalence of post-stroke insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews, 49, 101222.

Brown, D. L., Jiang, X., Li, C., Case, E., Sozener, C. B., Chervin, R. D., & Lisabeth, L. D. (2019). Sleep apnea screening is uncommon after stroke. Sleep medicine, 59, 90-93.

Cole, M. B., & Tufano, R. (2020). Applied theories in occupational therapy: A practical approach. SLACK Incorporated.

Edinger, J. D., Arnedt, J. T., Bertisch, S. M., Carney, C. E., Harrington, J. J., Lichstein, K. L., ... & Martin, J. L. (2021). Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of clinical sleep medicine, 17(2), 255-262.

Fink, A. M., Bronas, U. G., & Calik, M. W. (2018). Autonomic regulation during sleep and wakefulness: a review with implications for defining the pathophysiology of neurological disorders. Clinical Autonomic Research, 28(6), 509-518.

Glozier, N., Moullaali, T. J., Sivertsen, B., Kim, D., Mead, G., Jan, S., ... & Hackett, M. L. (2017). The course and impact of poststroke insomnia in stroke survivors aged 18 to 65 years: Results from the Psychosocial Outcomes In StrokE (POISE) Study. Cerebrovascular diseases extra, 7(1), 9-20.

Hepburn, M., Bollu, P. C., French, B., & Sahota, P. (2018). Sleep medicine: stroke and sleep. Missouri medicine, 115(6), 527.

Ho, E., & Siu, A. M. (2018). Occupational therapy practice in sleep management: A review of conceptual models and research evidence. Occupational therapy international, 2018.

Schepers, V. P., Visser-Meily, A. M., Ketelaar, M., & Lindeman, E. (2006). Poststroke fatigue: course and its relation to personal and stroke-related factors. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 87(2), 184-188.

Siengsukon, C., Al-Dughmi, M., Al-Sharman, A., & Stevens, S. (2015). Sleep parameters, functional status, and time post-stroke are associated with offline motor skill learning in people with chronic stroke. Frontiers in neurology, 6, 225.

Theadom, A., Rowland, V., Levack, W., Starkey, N., Wilkinson-Meyers, L., & McPherson, K. (2016). Exploring the experience of sleep and fatigue in male and female adults over the 2 years following traumatic brain injury: a qualitative descriptive study. BMJ open, 6(4), e010453.

Wickwire, E. M., Williams, S. G., Roth, T., Capaldi, V. F., Jaffe, M., Moline, M., ... & Lettieri, C. J. (2016). Sleep, sleep disorders, and mild traumatic brain injury. What we know and what we need to know: findings from a national working group. Neurotherapeutics, 13(2), 403-417.

Wiseman-Hakes, C., Colantonio, A., & Gargaro, J. (2009). Sleep and wake disorders following traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of the literature. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 21(3-4).

Zuzuárregui, J. R. P., Bickart, K., & Kutscher, S. J. (2018). A review of sleep disturbances following traumatic brain injury. Sleep Science and Practice, 2(1), 1-8.

Citation

Monti, Y.(2022). Treating sleep deficits in individuals with neurological impairment utilizing occupation-based sleep interventions. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5529. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com