Rhonda: Thank you so much. I really appreciate being here. This lecture is the first of two presentations related to pediatric feeding. In the first course, we are going to talk about typical feeding development. In the second course, we will talk about prematurity and the effects of early experiences on feeding.

Comprehensive Approach

Feeding development is comprehensive and holistic. The normal development of feeding is closely related to a child's overall developmental readiness. When I say developmental readiness, I mean that feeding coincides with the child's other developmental skills in the areas of motor, language, and oral motor. In addition to those areas, a child has to have physiological stability. They have to be able to breathe, maintain their own body temperature, and maintain healthy heart function to really be able to embark on a feeding process. This second point is that feeding is multisensorial, multifactorial, and multidimensional. It is involved in everything. We will talk about that as we progress today. Lastly, there is a basic, milestone timeline for the acquisition of feeding skills. There is going to be some variability because so many things have to align, and some kids are not going to meet their milestones at the same time. Some will have individual differences and things of that nature. We do not want to get too focus too much on this timing, but we do have a general timeline for what to expect.

The Senses and Feeding

We need to also think about the senses and feeding.

- Sight

- Sounds

- Smell

- Touch

- Sounds

- Vestibular

- Proprioception

There are a lot of senses involved in feeding. Think about that in terms of a bottle or breastfed infant. The baby is going to have a view of the bottle or the breast. They may have a view of the caregiver's face. The smell/taste for a breastfed baby is going to be a little more stimulating than for a formula fed baby because of all the different things that mom eats will be in the breast milk. The breastfed baby is going to get a little more stimulation as the breast milk will have different flavors each day, whereas formula is going to be the same every day. The baby may touch the bottle or touch the mom. The vestibular and proprioceptive systems are also being activated and are going to continue to develop. As the infant grows and is introduced to things like purees, finger foods, and solid foods, there is going to be a sensory explosion. They are going to be exposed to colors, textures, shapes, sizes, smells, and sounds.

A child is not only going to experience all of that stimuli in her mouth. She is going to be exploring it with her hands by playing with it, self-feeding, and feeding others. The child needs to have good equilibrium to be able to sit up and the proprioception of knowing where she is in space. She is then going to be able to reach out and grab a cookie off the tray or poke a fork into some food. We also have interoceptors. This is the part of the proprioceptive system that is in the guts and internal organs. This is important for hunger, lack of hunger, and sensations of internal organs. We really cannot discount any of this.

Hierarchy of Feeding

This is the hierarchy of feeding.

- Breathing

- Postural Support

- Eating

You may have heard some people say, "He'll eat when he's hungry." That is really based on some faulty information. Human beings have a hierarchy of function. Number one, a typically developing human needs to breathe. If eating gets in the way of that, they are going to choose to breathe. Postural support keeps us from falling out of a chair and hitting our head: that is the second instinctive function. The third is eating. If the first two are in peril in some way, that third one will not take place. We need to always keep this in mind when we are treating children who do not develop typically.

Environmental Factors

We also have to think about typical feeding development in terms of environmental factors.

- What is available to a child/family?

- What sources of nutrition are affordable?

- What is a child’s experience with tastes?

- What is a child’s health status?

- What is the status of a child’s hunger?

- What social norms dominate a child’s life?

- What nutritional needs does the child have?

We know different families have different environments. What is available to a child in the family? What are sources of nutrition that are affordable for that child? This will impact his development for sure. What is the child's experience with taste? Do parents love hot food? Do they love bland food? Do they love processed food? What is the child's health status? This will directly impact how that child is willing to explore and feeling good enough to take in food. What is the status of the child's hunger? In typical development, we hope that they have hunger and satiation. That will not always occur with kids who have had medically complex backgrounds. And then, what social norms dominate a child's life? In this particular household, do they use utensils? Do they use something else? Is the social norm in that family for everyone to overeat? Or undereat? Or only eat organic? Whatever happens to be the social norm for that family will also impact the child's development. Lastly, what nutritional needs does this child have? Some of these children will have some pretty hefty nutritional needs. But if you are talking just typical development, we just need to be cognizant of what the nutritional needs are and are they being met because that will impact how the child develops.

Relationships and Feeding

In terms of relationships and feeding, feeding is a hugely, relational process. When development is typical, the relationship is reciprocal in nature. Skills and attitudes develop in part by this infant and child watching family members and having healthy interaction with their caregivers. In the optimal setting, that child is beginning to participate very early and are being allowed to explore. They are communicating with their caregiver. Initially, this might be through eye contact, grimacing, crying, and things of that nature. But still, there is communication. The feeding relationship between the caregiver, the child, and the food is greatly dependent on a child's overall development. The feeding process is very important because it supports overall development.

Best Case Scenario

What is the best case scenario?

- Association of hunger to “time to eat”

- Communication of hunger is expressed

- Caregiver recognizes and responds

- “All done” is communicated

- The caregiver responds with cessation of feeding

In the best case scenario, there is structure, but there is no rigidity. The child learns to associate being hungry with eating. The child gets pleasantly full. He recognizes his caregiver as being someone who is important, who he can trust, and someone who makes it possible for him to get full, but does not push him to eat more than he wants.

Caregiver-Child Relationship

Along those lines, Ellen Satter is a phenomenal dietitian. She talks about the division of responsibility.

- Infants

- Parent is responsible for what the infant consumes

- The infant is responsible for how much (and everything else)

- Infant transitioning to family food

- Parent is responsible for what (become responsible for when/where)

- The infant is responsible for how much and whether

- Toddlers-through-adolescents

- Parent is responsible for what, when and where

- The child is responsible for how much and whether

Essentially, parents of infants and children are responsible for providing nutritious food from birth. Once the infant begins to transition from bottle or breast to more foods, the parents continue being responsible to give that nutrition. They also are responsible for when and where that nutrition is offered. However, the infant or child is responsible for how much he or she is comfortable with eating, and whether he or she eats it all. This is very important. A dysfunction in this relationship can wreak havoc on typical feeding development.

Typical Feeding Environment

Much like a lot of the other developmental processes, children learn best about eating from a very positive natural environment: when they can observe, when they can play, and when they are present when family members doing something very natural like eating, like growing food, like going to the grocery, preparing food, eating, and even cleaning up.

- Baby/child present during family meals

- Baby/child plays with water/food/utensils/cups/dishes

- Baby/child observes family preparing food/eating food/enjoying food

This is optimal for that child to be completely engaged with that family. This is what happens in typical feeding most of the time.

Neurophysiological Development

We have to consider also neurophysiological development. This is critical.

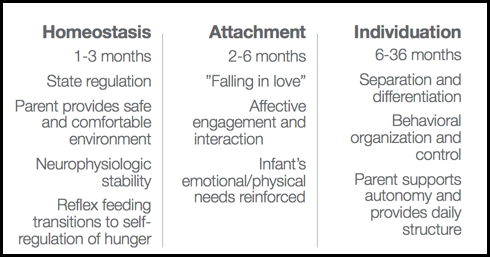

Figure 1. Neurophysiological development between 1-36 months.

We know that between one to three months, that homeostasis is becoming established. This is simply an infant's ability to regulate their state. In this particular period, the parent provides a safe and comfortable environment to help to make that happen. The child will then have neurophysiologic stability. They will also have reflex feeding transitioning, "I am hungry now. It's time to eat." Overlapping that, if all goes well with homeostasis and it is established, we can see attachment. Attachment is usually between two and six months, and this is the falling in love stage. This is where that affective engagement and interaction between mommy, daddy, and other adults and baby occurs. We smile at each other. We start to fall in love. The infant is getting his or her emotional and physical needs not only met but reinforced. If homeostasis occurs and attachment is able to emerge, then individuation can occur. This is where we get our "terrible twos." In the six to 36 months stage, this is when that person says, "Wait a minute, I am separate from you. I am an individual. I am going to organize some of my own behavior and exert some of my own control." In a perfect setting, the parent is going to support the autonomy but is also going to provide the very much needed daily structure and continue to be the parent. Now, what does this look like in terms of feeding?

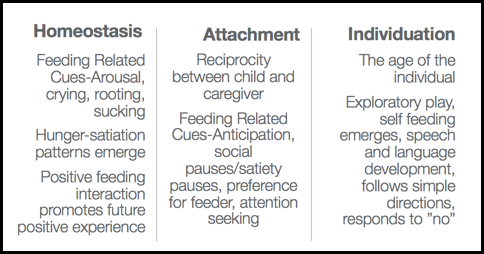

Figure 2. Homeostasis, attachment, and individuation in relation to feeding.

In homeostasis for feeding, we see arousal cues. We see crying, rooting, and sucking that says, "I need to get in here and be regulated with some feeding." Hunger and satiation patterns begin to emerge. A positive feeding interaction will promote future positive experiences. In an attachment, you see reciprocity between the child and caregiver. During feeding, you might see the infant open his or her mouth for the spoon. You might see social pauses where he or she stops on the bottle or stops on the breast, to kind of smile at mom or vice versa. You might see a preference for a feeder emerging. "Mommy feeds me with my bottle, and she does not push me, but, Grandma pushes me." They might interrupt to be able to get a little attention back and forth. Lastly, if all goes well, we see nice individuation. This is where a child's exploratory play and self-feeding emerges. "I want to do it" emerges. Speech and language development emerges. We cannot discount the importance of speech and language development in this feeding process. I always say to my students, "If we do not have the language to talk about food, it certainly is going to inhibit us a lot of times." For example, if you go to a foreign country and do not speak the language, you cannot ask about the food or how it was prepared. You are much less likely to feel comfortable engaging, touching, and putting that food in your mouth. This is the same for these children at the individuation stage. They want information, and they want to be able to communicate with you about it. These are all phases of neurophysiological development that have to occur during typical feeding.

Temperament Theory

Now along these lines, let's think about temperament theory for a moment (Thomas et. al., 1970).

- Categories of personality styles that persist through life

- Personality styles based on activity, adaptability, intensity, mood, persistence, distractibility, regularity, responsivity, approach/withdraw

- Relates to how individuals manage in relationship to novel situations

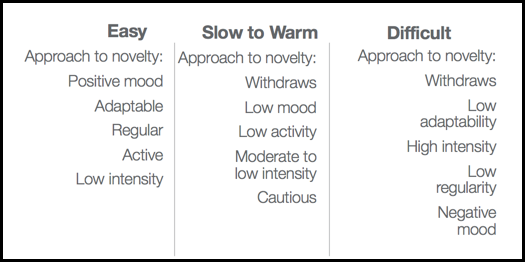

Temperament theory involves categories of personalities will occur and persist. They relate to activity, adaptability, and how someone will respond to novel things. Think about eating. You may have read Marsha Dunn Klein's work. I remember reading something one day of hers that hit me in the face. I thought, "Wow, this makes so much sense." It was the fact that when you have a plate of food, every time you take a bite, it changes. The visual aspect of it changes to some degree. It begins to get cooler as it sits on your plate. The shape of the food changes. If you have a child who likes a particular shape or consistency, then this is a novel experience. There are a lot of new foods and experiences that are coming toward this child. The temperament of that child is going to influence that. Let's now look at this next slide in which we can see the categories.

Figure 3. Temperament categories.

For an easy temperament child, the approach to novelty like new foods, new utensils, new settings, new feeders are going to be pretty positive. They are pretty adaptable and go with the flow. They are active but have low intensity. This is not a big deal to them. The slower to warm child is going to be a little different. They might withdraw a little bit. They might have a lower activity level, moderate to low intensity, and are not 100% ready to jump in and engage. They are cautious. I think we can all appreciate that. Even if you happen to be one of those easy people, if you are confronted with a novel situation that is atypical, you might be a little cautious. Then, we have the difficult temperament. The approach to novelty with this child is that they are going to actively withdraw. Adaptability will not be good. High intensity will be present. When I say that, I mean a negative high intensity a lot of times. They have low regularity and are not able to regulate themselves. They also have a negative mood. When we have a child with a difficult temperament and try to introduce new foods, this will impact typical development. We may not see as broad a range accepted which we have to consider when we are thinking about typically developing children. Because as I said, they are all individuals. They are all going to be across this span of categories and dipping into each of the categories, but still overall having these general personality types.

Anatomy (Infants and Children)

We are now going to look at all of these anatomical areas.

- Oral cavity

- Pharynx

- Nasopharynx

- Oropharynx

- Hypopharynx

- Larynx