Overview of Autism and Common Feeding Problems

Overview of Autism

- 1 in 59 children is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), per the CDC (2018)

- 1 in 37 boys

- 1 in 151 girls

- Children with autism are nearly five times more likely to suffer from one or more chronic gastrointestinal disorders than are other children.

- The estimated prevalence of feeding problems in children with autism has been reported to be as high as 90%, with 70% of children described as selective eaters (Volkert & Vaz, 2010).

- Evidence suggests that the presence of feeding difficulties in infancy may be an early sign of autism (Volkert & Vaz, 2010).

About one in 59 children now are diagnosed on the spectrum. These children are five times more likely to have chronic gastrointestinal disorders compared to neurotypical children. It is also estimated that about 70 to 90% of this population has feeding issues. It is now being studied that feeding difficulties could be an early sign of autism in infancy.

Feeding Disorders Observed in Children with Autism

- Food selectivity or picky eating

- Food neophobia (persisting)

- Food refusal based on texture

- Limited fruit/veg intake (vegetables are the most commonly omitted food for children with ASD)

- Preference for starches

- Unable to tolerate small changes to the appearance of foods

- PICA

- Gagging or choking on foods

- A high degree of parental stress regarding balanced intake

- Rule out any medical explanations or food allergies that could be causing a dislike of particular flavors or food groups

- Identifying the brain/gut connection and bodily experience can be difficult to describe. It is always important to consult your pediatrician, gastroenterologist, or appropriate specialist to investigate these possibilities before starting any new eating or treatment plan.

Some of the most common symptoms that we will see for kids on the spectrum in the clinical setting are picky eating or refusal based on texture. There are also sensory components and limited intake of certain nutrients, specifically fruits and vegetables, with vegetables being the most commonly omitted from the diet. There can also be some very rigid preferences for starches and carbs. Often, we refer to this as a bland or tan diet with kids eating mostly crackers, bread, and those types of foods. PICA is also very commonly observed in this population. This is eating non-nutritional items like paper, dirt, and clay. Interestingly, PICA is very heavily related to nutritional deficiencies, making sense for this population.

Brain-Gut Connection

Overview/Research

- The Gut-brain relationship is studied as a possible etiology and symptomatology of ASD (Doenyas, 2018).

- Understanding how nutrition and diet impact the gut microbiome and thus the brain is vital for understanding nutritional interventions for individuals with ASD.

- Nutrition impacts brain and behavioral development throughout the entire lifespan.

- Nutrition provides the genes with necessary molecules needed to meet their potential and targeted effects on the brain's growth and development.

- Nutrients are required for certain functions of the brain, and the levels of these nutrients impact the function (Rosales, Reznick, & Zeisel, 2009).

A lot of what we will be looking at today has to do with the brain-gut connection. We need to understand what this means for how nutrition is really impacting our impacts cognitive and neural functioning. It is now being studied as a possible etiology and symptomology of autism.

Brain-Gut

- Bidirectional signaling between the gut microbiome and the brain

- The gut microbiome is the organisms, including bacteria and fungi, within the digestive tract.

- The gut impacts neurotransmitters in the brain, affecting stress, anxiety, mood, and behavior, while the brain impacts the gut’s motility, secretion, nutrient delivery, and microbial balance.

- The Enteric Nervous System (ENS): runs from the esophagus to the anus, in the lining of the digestive tract

- Composed of 500 million neurons, five times the amount found in the spinal cord

- The ENS is responsible for

- Sending signals to the brain to affect changes in mood

- Communicating with your immune system, alerting an immune response to remove the bad bacteria

When we look at this relationship between the gut and the brain, we need to understand that this is a bi-directional occurrence between the gut and brain. Previously, it was believed that the brain only impacted the gut. For example, with symptoms like anxiety and depression, many thought that this caused GI symptoms as this was commonly seen in people with anxiety and depression. They would have diarrhea, constipation, and those GI symptoms. Now we know that this is coming from the gut and impacting the brain.

Serotonin is a chemical in the body, and we refer to it a lot as the happy chemical. It influences our moods and behaviors, and 95% of the serotonin in the body is made within the gut. We are now starting to understand how these two systems interact and how they are not independent. Instead, they influence each other.

When we talk about the "gut," it is not just the stomach. We are talking about the entire enteric nervous system from the esophagus to the anus. The digestive tract lining is composed of about 500 million neurons, which is five times the amount that is found in the spinal cord. A lot is going on there, which helps us understand the importance of all of this.

Signs of Gut Microbiome Distress

- INFLAMMATION

- Mood Swings

- Lethargy

- Behavioral changes

- Irritability

- Sleep problems

- Allergies or Food intolerance

- Skin rashes

- Stomach bloating

- Diarrhea

- Poor attention

- Forgetful

- Crying

- Tremors

- Depression

There are different signs of an imbalance or distress that happens within the microbiome. Specifically for kids on the spectrum, I want to highlight allergies, food intolerances, and skin rashes. These are common things in this population. Many kids with autism have eczema as an example. These are caused by the gut and can be healed by the gut. Inflammation is bolded because that is a word that you will hear a lot today. Any topic about gut health usually involves inflammation.

In an ideal state without inflammation, tight junctions will keep the materials and the bacteria within the gut. When there is an immune response that causes inflammation, the lining will expand, which will create gaps and junctions. This is what we refer to as a leaky gut, gut permeability, or gut dysbiosis. All of those words get thrown around, but when these openings and junctions exist, then peptides, neurotoxins, and endotoxins can travel through the bloodstream and eventually to the brain. They can synapse with the neurotransmitters and impact different parts of mood, cognition, function, et cetera. This gut permeability then impacts the symptoms of autism, like social ability, eye contact, mood, and rigidity.

Factors Influencing the Gut Microbiome

- Nutrition

- Antibiotic use

- Method of birth delivery

- Probiotics

- Breast vs. formula feeding

- Sleep quality

- Physical activity

Many factors influence the microbiome. Nutrition is obviously one, and we will talk a lot about that today. Another is antibiotics. Kids on the spectrum have many chronic infections, the most common one being ear infections. To treat this, antibiotics are typically used. Antibiotics serve a purpose, but when we use an antibiotic, not only does it kill the bad bacteria that we are trying to fight, but it also can destroy some of the good. This is going to cause an imbalance within the gut. The issue with antibiotic use is that it can be repetitive use. A child is on an antibiotic, and then they come off of it, but two months later, they are on another one. The gut does not have time to heal. Studies show that the gut can take between six months and two years to heal completely from the use of one antibiotic. Thus, when we have that repeated exposure without any chance for healing, we see these imbalances.

The type of birth delivery is going to impact the biome as well. In utero, everything is forming; hence the microbiome is in a state of homeostasis and balance. Research shows that at birth, the microbiome starts to diversify. Children born through vaginal delivery will be exposed to many bacteria in the vaginal canal, which will help diversify the microbiome. Children that are born through cesarean section are not going to have that same exposure. This is why research is looking at different alternatives and methods to help support this. An example is vaginal swabbing to help children born cesarean to have bacterial exposure healthy for creating a well-diversified microbiome.

Probiotics are used to feed the good bacteria within the gut. We will talk about those more as a form of supplementation. Breast and formula feeding are very similar to birth delivery. A breastfed child will be exposed to good bacterial strains from mom, and a child that is formula-fed most likely would benefit from probiotic use to have those exposures. Sleep quality and physical activity, like so many other elements of life, also impact the gut.

Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Children with ASD

- Incidence rates of GI issues associated with ASD vary among studies; however, there is a common conclusion that a relationship exists.

- Penzol et al., 2019: one-third of ASD patients in the sample had at least one GI issue

- GI issues were associated with sleep problems and behavioral problems (Penzol et al., 2019)

- 2014 study suggests that children with autism are about 5x more likely than neurotypical children to have symptoms such as constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal discomfort (McElhanon et al., 2014)

- Children with autism are at an increased risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Lee et al., 2018)

- IBD includes: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Based on 300,000 children in the United States, children with autism are 67 percent more likely than typical children to have a diagnosis of IBD

- Penzol et al., 2019: one-third of ASD patients in the sample had at least one GI issue

- Most common gastrointestinal problems seen in children with ASD include: constipation/distention, gut permeability/leaky gut, and diarrhea

Children on the spectrum are five times more likely to have GI symptoms. They also have an increased risk for different inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis. One study on 300,000 children in the United States showed that children on the spectrum are 67% more likely than neurotypical children to have some of these different GI disorders. Most commonly, when we look at children on the spectrum, we see symptoms like constipation, diarrhea, and gut permeability. Something very challenging with the nutritional piece and GI piece of intervention is there is limited communication. And, even if a child has adequate communication, the ability to understand these symptoms and express them in a way that can be understood by adults and their environment is tough for these children. Many times, these symptoms go diagnosed, or the diagnosis is delayed.

Specific Macro/Micronutrients That Impact Neural Functioning

- Choline (learning and memory)

- Iron (attention and memory)

- Zinc (needed for cell death)

- Folic acid/Folate (cognitive performance)

- Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and essential fatty acids (neurodevelopment and visual acuity)

- Vitamin B6 (balance of excitatory/inhibitory system function)

- Vitamin B12 (neurologic function, fatigue)

- Magnesium (serotonin and dopamine synthesis)

There is a lot of foundational work to overcome this, depending on the age and severity of dysfunction of the child. Understanding that nutrition has specific and certain roles within the body, specifically within the brain, is a good start. A lack of nutrients will negatively affect things like learning, memory, attention, and the synthesis of serotonin. We have to understand what nutrients are needed, what is missing, and how to bridge that gap.

Factors Impacting Food Choices

- Socio-economic status

- Low socioeconomic status leads to inadequate dietary intakes, nutrient deficiency, and eventually, morbidity and mortality (Rosales, Reznick, & Zeisel, 2009).

- Malnutrition and decreased consumption are connected to learning deficits and intellectual development deficits.

- Education

- Mothers with higher knowledge of nutrition more often have children with normal body weight.

- They are also more likely to feed their children vegetables, fruits, legumes, and less likely to give them sugary drinks like soda or juice and avoid fast food and foods with artificial ingredients. Overall, they typically consume decreased levels of fat and cholesterol and increased dietary fiber.

- Mothers with higher education and their children scored higher on assessments regarding healthy eating habits (Yabanci, Kisac, & Karakus, 2013).

- Nutrition labels

- Access

- Geographical location

- Grocery store choices

- Finances

- Inadequate food

- Storage facilities

- Cooking facilities

It is not as simple as providing feeding therapy and support. Many factors influence what food we eat and what food children are served. As therapists, we have to get creative with what we are doing and understand what some families might be facing. Access is one of the most limiting factors. There are food deserts in America where it is tough to get fresh fruits and vegetables and organic foods. Finances are another issue. They may have limited resources at home. I was naive about these issues before I started practicing in home settings. Not every family has a stove, freezer, or refrigerator. We have to take that into account when we are creating a home program for them. Socioeconomic status and finances have been linked in research to nutritional deficiencies and inadequate dietary intake.

Education is an interesting piece. Research shows that parents that have higher levels of education feed their children more nutritious foods. Part of this is being able to read and understand nutrition labels. Nutrition labels are confusing even to very educated people. Helping parents to have strategies for that is really important. I like to give simple tips for nutrition labels, like if you cannot read any of the ingredients lists, most likely they are synthetic. I also like to educate families on buying foods with short ingredient lists. Foods with fewer ingredients have fewer chemicals and are better for you.

Nutritional Intervention Strategies

- Gluten-free and Casein-free Diets

- Ketogenic Diet

- Specific Carbohydrate Diet

- Probiotic Supplementation

- Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Supplementation

- Dietary Supplementation

For this population, we will look at some different diets used and researched, and we will also look at supplements. The research on nutritional interventions, specifically for kids on the spectrum, is limited. They are limited mostly by sample size and the duration of the study. We know the gut takes a long time to heal, and diet changes do take weeks to months to affect the person. We need more studies that are completed over a longer period with larger sample sizes to evaluate an intervention's efficacy.

Gluten-free and Casein-free Diets (GFCF)

- Excluding gluten (wheat and grain product) and casein (protein in dairy products)

- The rationale for use:

- Gluten and casein digestion release opioid peptides, which decrease the uptake of sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine- CYS) by cells, decreasing glutathione (GSH) levels.

- Opioid peptides also decrease the methylation index, altering DNA methylation and gene expression patterns.

- Decreased GSH levels in the GI tract increase inflammation and impact GI dysfunction and symptoms of GI discomfort.

- GI inflammation is common symptomology of autism and is linked to an increase in hyperpermeability (leaky gut).

- 25.6% of children with ASD compared to 2.3% of neurotypical children have increased intestinal permeability

- Gut permeability allows for increased systemic effects from opioid peptides.

- Some systemic effects include: social behavior and the pathogenesis of ASD

- Individuals with ASD are also noted to have increased antibody levels for a group of dietary proteins, including gluten/gliadin and milk proteins. The GFCF diet has been shown to decrease these antibody levels.

- The goal of the GFCF diet is to improve CYS absorption and levels of GSH.

(Karhu, E. et al., 2020)

The gluten-free and casein-free diet is one of the most popular diets for kids on the spectrum. The rationale behind using it makes sense as it affects gut inflammation that I touched on earlier. When a person digests gluten or casein, those proteins cause a release of opioid peptides. This decreases the glutathione levels within the body or the GI tract. Those decreased glutathione levels cause inflammation. Simply put, if we eliminate the digestion of gluten and casein, we will have a balanced level of glutathione and not cause inflammation. Again, inflammation is related to increased gut permeability. Studies show that traveling opioid peptides impacts social behavior, so that is why that is being so linked to kids on the spectrum.

Ketogenic Diet

- Diet focuses on fat and protein and low carbohydrate intake, which causes the body to use fat metabolism as a primary source of energy

- This diet has been studied regarding ASD with a focus on minimizing the behavioral symptoms associated with the disorder

- Animal studies have shown that the Keto diet improves sociability in communication and decreased self-directed receptive behaviors (mouse model)

- Another animal study found improvement in myelin formation, neurotransmitter signaling, and white matter development

- Keto was observed to reverse abnormal basal sensorimotor excitation/inhibition pathways in a mouse model of ASD

- Gut microbiome health was also observed with this diet intervention, proposing that ketogenic diets could alter the gut microbial composition and decrease neurological symptoms based on the gut-brain axis.

(Karhu et al., 2020)

The keto diet is a commercialized weight loss diet. I included this because there is research on it. However, I think it would be hard to implement in practice because it is focused on fats and proteins and limits carbs. Many kids on the spectrum are carb-heavy, and it would be hard to eliminate those foods without giving them alternatives. Theoretically, I understand it, and the research supports it, but it seems like it would be very hard from a practical standpoint. The diet has been shown in animal studies to improve sociability, communication and decrease some of the rigid and repetitive behaviors often seen with kids on the spectrum.

Probiotic Supplementation

- Probiotics work in the gut microbiome to decrease GL inflammation and intestinal permeability.

- One study of children ages 2-9 with ASD found that probiotics reduced inflammation in the intestines and restored the GI microbiota resulting in improvement in ASD symptoms.

- Another study found that probiotics possibly reduced the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in late childhood.

- Theories for the probiotic influence of ASD:

- Opioid-excess theory (same as GFCF), more specifically that probiotics would help to process gluten with less damage to the gut or peptide leakage

- Anti-inflammatory properties of probiotics could combat the inflammatory immune response of individuals with ASD, which would, in turn, support improvement in behavioral issues

- Correct gut dysbiosis and decrease the production of endotoxins, reducing gut permeability and inflammation and removing the ability of the endotoxins to impact the CNS

- Good Bacterial strains: Lactobacillus and Clostridium are decreased, while pathogenic bacterial strain Candida is increased in individuals with ASD compared to neurotypical peers, which is evident of gut dysbiosis

(Karhu et al., 2020)

Probiotics work within the gut to combat inflammation and decrease permeability. They are food for the good bacteria within the gut. Probiotics are complicated because there are so many different strains. There are different strains for different purposes and at different periods of life. Probiotics in infancy are important to support growth and development. One study found that children ages two to nine on the spectrum had reduced inflammation and had a more balanced gut microbiome after probiotics. This resulted in some improvement in symptoms of autism. Probiotic supplementation decreases inflammation and damage as opposed to removing the foods that cause it. In one study, individuals on the spectrum were noted to have increased pathogenic bacterial strains and decreased beneficial bacterial strains within the gut. There will always be good and bad bacteria within the guts, but we always want the good to outweigh the bad. As long as the good outweighs the bad, we will not have an inflammatory immune response.

Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD)

- This diet aims to decrease symptoms of carb malabsorption and the growth of pathogenic intestinal microbiota by reducing the intake of complex carbs.

- Use for this for autism comes from the continued research on gut dysbiosis, poor carbohydrate digestion, and absorption for those with ASD

- One case study found that SCD improved GI symptoms, nutrient status, and behavioral domains for patients with ASD.

- There is a lack of published evidence for the safety/efficacy of this diet for ASD. Additional research is needed for this diet.

(Karhu et al., 2020)

Another diet is the specific carbohydrate diet, which helps combat the symptoms of malabsorption of carbs. Kids on the spectrum with carb-heavy diets have difficulty absorbing some of the different proteins. This causes pathogenic bacteria to increase within the microbiome.

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PSFA) Supplementation

- PSFAs include: arachidonic acid (AA), eicosatetraenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)

- Required for typical brain growth and development, identify in areas of the synapse, memory formation, and cognitive function development

- A theory that polyunsaturated fatty acids may be a mechanistic pathway for the development of ASD

- Several studies show individuals with ASD have altered phospholipid fatty acid compositions in plasma and blood cells.

- One systematic review found that supplementation was shown to significantly improve social interactions, repetitive and rigid interests, and behaviors (studies limited by small sample size and short duration)

- Another review found a small, but statistically significant benefit to supplementing PSFA

(Karhu et al., 2020)

Polyunsaturated fatty acids, like DHA, are essential for brain growth and development. In fact, formulas are fortified with it as they are important for different cognitive processes like neural synapses and memory formation. And it has been linked to autism. One systematic review found that supplementation showed significant improvement in social interactions, repetitive and rigid interests, and behaviors. Again, these studies were limited by small sample sizes and short durations.

Dietary Supplementation

- Dietary deficiencies are an area being identified as possible triggers for the pathophysiology of ASD, with a specific focus on vitamins A, C, B6, B12, folate, D, and ferritin.

- Vitamin A

- Deficiency is common for those with ASD

- A pilot study found supplementation to cause significant improvement with ASD symptoms but warn it may only be recommended for a subset of children with ASD

- Not proven effective as a treatment for ASD symptoms

- Vitamin B-12

- Supplementation increased levels of glutathione (which reduces oxidate stress) and SAM (required for methylation)

- Levels of methyl-B12 in young individuals with ASD were found to be significantly decreased compared to same-aged controls representing a premature acceleration of normal age-dependent decrease. This lower methyl-B12 level was associated with lower MTR activity, and impaired methylation interferes with gene expression required for normal brain development, supporting the rationale for B12 supplementation in ASD.

- Vitamin C

- Children on the spectrum have below the average intake of vitamin C compared to neurotypical peers.

- Supplementation of vitamin C in studies have shown excess intake for children 2-3 years old; increased levels may be beneficial to target oxidative stress

- In a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study, children with ASD that received vitamin C supplementation had clinically significant oxidative stress reduction.

- Folate

- Folic acid supplementation in pregnancy could reduce the risk for ASD.

- Women who are folate receptor autoantibody (FRAA) positive could benefit from high dose folinic acid to reduce the risk of the child being born with ASD.

- High dose supplementation showed improvement in verbal communication for children with ASD.

(Karhu et al., 2020)

Dietary supplementation looks at different vitamins and their impact. This is one of the most plausible and realistic ways to look at dietary intervention, especially for kids on the spectrum and picky eaters. We can supplement the vitamins and nutrients that they are missing. At the same time, from a therapeutic standpoint, we can use therapeutic strategies to expand their diet, affect their oral motor skills, and address sensory processing. Nutritional intervention can help to decrease the poor gut symptoms and negative symptomologies with ASD. There have been some promising studies with folic acid and folate looking at increased communication and sociability of kids on the spectrum.

Some of this gets complicated. We need to have a multidisciplinary team to address this as it matters what supplementation you use. For example, for folate and B12, we want to use a methylated version of that. Folic acid, a synthetic form of folate, needs many more steps to break it down. It makes it less bioavailable to the body. We want to use the best form of a supplement so that it can be absorbed.

We are now going to move into some of the therapeutic interventions. Again, the nutritional piece is going to be the foundation for feeding therapy. We need to address that first with the help of a GI nutritionist or a dietician to optimize the child's cognitive function and sociability.

Therapeutic Intervention Strategies for Picky Eating

- Sensory Systems

- Food chaining

- Liquid Consumption/Cup Drinking

- Chewing, Utensil Use, and Self Feeding

- Visuals

We can use therapeutic intervention to support and expand on picky eating behaviors. We have to look at each system. Often, the tactile system is discussed regarding feeding, but that is definitely not the most influential system or the only system that we need to address. We will look at each sensory area and discuss the impact on feeding and some strategies.

Sensory System: Auditory

- Impact on Feeding

- The environment can positively or negatively impact feeding; a loud setting may trigger an adverse response for an individual with hypersensitivity, while music may support a hyposensitive individual to be able to better concentrate on mealtime

- The noise caused by crunching food during chewing can be overwhelming and overstimulate those that are hyposensitive. This can be so impactful that it causes anxiety with mealtime and decreases consumption.

- Intervention Strategies

- Hypersensitivity

- Noise-canceling headphones

- Quiet, calm environment for eating

- Provide visual schedule or visual instructions, so they aren’t relying on verbal cues; pictures are helpful

- Reduce distractions during mealtimes

- Hyposensitivity

- Background music

- Therapeutic listening (requires a therapist)

- Auditory memory games

- Practice meaningful listening (play music and have the child tap every time they hear a certain sound)

- Hypersensitivity

The auditory sensory system includes noise in the environment, and this can be positive or negative. For example, one child may benefit from light, calming music, but that could be distracting to another. A hectic home environment may make it hard for a child to eat. We may have to think about those components when setting up an environment and deciding where mealtime will happen. We also have to consider other environments like school. It also might not be a mealtime where we need to try new foods or stress certain things. The most important thing is to make the experience as comfortable as possible. If they are having a hard time with auditory input, we also need to note that it might also be impacting what is happening in their mouth. When you are chewing something really crunchy, that can be very loud in your head. If a child is hypersensitive to that, the result may be that they do not want certain textures or types of food. You can look at the different intervention strategies for a hyper or hyposensitive to the auditory input.

Sensory System: Tactile

- Impact on Feeding

- A child with tactile defensiveness may react in extreme ways to different foods and textures presented at mealtime.

- Reactions may include:

- Throwing food from tray/plate

- Removing with utensils

- Trying to elope from room/area with food item

- Crying, distress, anger

- Gag response when touching or eating

- Requests to wipe hands or constantly face during mealtime or messy play

- The touch receptors on the lips and tongue tell the brain information about the food being eaten, including size, temperature, and texture. This is what alerts us to lick our lips when there is a mess or chew until food particles are small enough to be swallowed. Chewing on crunchy foods can create a calming sensation for some children, while mushy/soft foods can overstimulate a child, causing gagging or even vomiting.

- Mixed textures are complicated to navigate as the tongue has to differentiate between the textures; some may require chewing while others don’t (like ice cream with fruit toppings). Some children are not able to discriminate between these textures safely, which causes food refusals.

- Intervention Strategies

- Tactile Defensiveness

- Engage in messy play and messy meals daily. In order to decrease defensiveness, we have to support exposure and build tolerance.

- This should be gradual and at your child’s lead. Start with textures they have no aversion or mild aversion to and build on those before moving to more challenging textures.

- Engage in messy play and messy meals daily. In order to decrease defensiveness, we have to support exposure and build tolerance.

- Sensory bins(with and without food items)

- Deep Pressure

- Weighted options (lap pad, blanket, vest)

- Sleep Sleeve

- Cozy Canoe

- Compression

- Clothing, tight hugs, squeezes

- Brushing Protocol (therapist supervision required)

- Tactile Defensiveness

Tactile sensation has tons of implications for feeding. It is not necessarily as foundational as other areas and should not be the main focus of intervention like we see so often. A child removing food from their tray, throwing it, trying to elope from an area, or gagging after touching or trying a food indicates issues in this area. If they are gagging before eating, that is the visual system issue. Thus, we need to note when a child is gagging and what system is being impacted.

There are many different parts of the tactile system where we can help. If you do any pediatric feeding, then you know the importance of messy mealtimes. This concept is hard for parents. Common things that I see are parents constantly wiping their children's faces and hands and scraping utensils against their children's faces to remove the mess. This is very confusing from a sensory and a neurological standpoint with all of these different inputs. We only want to provide input at the mouth and in the mouth. When we are wiping all over the face and hands and focusing on so many different things, it is confusing.

We want to support a lot of tactile input. One of the best intervention strategies is playing with food. It is a great way to incorporate that tactile sensation to incorporate that into mealtime later. Picky eaters have a lot of anxiety and stress-related to mealtime. Being in the high chair or at the table may automatically put them into a fight or flight response. This decreases their appetite, and they are not in a learning state. I like to use plastic or felt food and use that in play. Once they get comfortable with that, then I start to incorporate real food items into play. An example might be making a necklace out of cereal or counting with blueberries. You can expose them to the food without the pressure of eating.

Sensory System: Gustatory

- Impact on Feeding

- Hyposensitive (under-responsive): they require a lot of input in the mouth to register and process taste

- This may look like this:

- prefer bold and spicy flavors

- only eat cold or hot foods

- may heavily season or use excess dip/condiments with food

- smelling, mouthing, chewing inedible objects frequently

- This may look like this:

- Hypersensitive (over-responsive): easily overwhelmed and defensive to oral input/exposure

- This may look like this:

- preferring food at room temperature with bland tastes

- mixed textures can be tough to eat

- frequent gagging during meals

- avoiding a variety of tastes, textures, or temperatures

- This may look like this:

- Hyposensitive (under-responsive): they require a lot of input in the mouth to register and process taste

- Intervention Strategies

- Hyposensitivity

- Chew tools (How to Choose the Right Chew)

- Vibrating feeding tools

- Utilize preferences for spices, crunchy texture, dips, etc. to expand on the food list

- Ice chips are a great way to increase hydration and water intake for a picky eater who avoids plain water but seeks oral input

- Oral/facial massage and vibrating input for regulation

- Drink/suck thick liquids (smoothie) through a straw

- Chewy and crunchy snacks throughout the day (carrots, pretzels, jerky, dehydrated fruits and vegetables, yogurt, and puree squeeze pouches)

- Blowing activities (blow bubbles, whistle, party blower)

- Hypersensitivity

- Ease into mixed textures, utilize dipping and light spreads to introduce these combinations

- Serve foods with mild smells, don’t burn candles or use smelly fragrances in the eating area as smells impact taste

- Chew tools and vibration for desensitizing oral cavity

- Use other daily routines like brushing teeth to work on oral tolerance (usually, hypersensitive kiddos won’t enjoy brushing teeth--use just water, try various toothpaste, or different brushes (both regular and vibrating)

- Hyposensitivity

For the gustatory system, we are looking at hypo- or hypersensitivity with tastes and oral sensation. Those with hypersensitivity might prefer or benefit from bold and spicy flavors as bland foods might be harder for them to interpret. They may also have a temperature preference and be very highly dependent on condiments. This is frequently observed in kids on the spectrum. There are many different strategies that you can use for the gustatory system listed above.

Sensory Systems: Olfactory

- Impact of Feeding

- Hypersensitive: a heightened sense of smell

- Poor tolerance of everyday smells, easily overwhelmed

- Gag easily during mealtimes (just from smelling) and tend to have limited food lists

- Complain about smells from food others are eating, quickly overwhelmed in restaurants and confined places with many food scents

- Are uncomfortable with some clothing and prefer only certain items that smell a preferred way

- Hyposensitive

- Chew and mouth inedible objects, always exploring the environment with nose/mouth to try to get more input

- Intentionally smell food and nonfood items frequently as an attempt to get input

- Lack of awareness of everyday smells

- Hypersensitive: a heightened sense of smell

- Intervention Strategies

- Hypersensitivity

- Be aware of mealtime environment, eat outside or with windows open to decrease smells

- Cook foods that have a minimal aroma

- Desensitize to smells-smelling games like scratch and sniff stickers with mild and familiar smells and gradually introduce more intense and various smells

- Scented markers

- Games

- Use a preferred essential oil on the wrist or base of the nose (depending on tolerance) to use as a sniffing option in public to overcome non preferred smells

- Hyposensitivity

- Smelling games (use essential oils on cotton balls and have child guess/label scents) to increase awareness and processing of smells

- Use bold and robust recipes to encourage eating and mealtime acceptance

- Use spices, dips, and sauces in order to expand diet

- Hypersensitivity

When we look at the olfactory system (smell), it is hard to separate from the gustatory system. They are different but complimentary of each other. This is definitely an area where gag comes into play. We have to try to differentiate between a gag from the smell versus a gag from the sight of food. A heightened gag reflex is common for kids on the spectrum.

The three systems that we want to look at particularly for a gag reflex are the sight of the food (visual presentation), the smell of the food, and taste. You have to delineate between these. It becomes easier if you watch children over multiple sessions and purposely eliminate each of those.

I have had a lot of success from introducing smells during therapy and including that in a home program. I like to use essential oils and add that to playdough. If the child is high functioning and tolerates it, you can have them close their eyes or use a blindfold and smell different cotton balls. They can keep their eyes open, but it engrosses them in smell if they close their eyes.

With tactile, visual, olfactory, and gustatory systems, we want to increase the acceptance and tolerance of the different sensations instead of eliminating them because they are not preferred.

Sensory Systems: Vestibular

- Over-Responsive

- Difficulty walking, crawling, maneuvering on uneven surfaces, or when changing directions

- Spinning, jumping, and running can cause disorientation

- Avoids playground equipment (slides, swings)

- Jumping and climbing can be challenging due to gravitational insecurity (don’t want both feet to leave the ground simultaneously)

- Under-Responsive

- Movement seekers, constant motion- enjoying spinning and running

- Often participate in these movements for extended periods that would typically cause dizziness or even nausea for others

- Often spin in circles or rock body back and forth for input

- Impact on feeding

- Difficulty sitting and maintain the posture for mealtime

- Difficulty bringing/coordinating food to the mouth

- Intervention Strategies

- Vestibular input and strategies are helpful for both over and under-responsive kiddos. For those that are under-responsive, the activities can be more intense, last longer, and provide more input while approaching the same tasks in the opposite manner will benefit over-responsive children and help them build tolerance and understanding of their vestibular system.

- Spinning:

- Sit and spin

- Merry go rounds

- Scooter boards

- Swings- tire swing, platform swing, snuggle swing

- Inversion

- Yoga

- Rolling, cartwheels

- Jumping

- Trampoline

- Jump down from higher surfaces (stairs, couch)

- Balance

- Balance board

- Yoga

- Spinning:

- Positioning is crucial for mealtime. The child must have proximal stability in order to have distal mobility, meaning their body needs to be supported so that their arms/hands can move freely without the need to support their body in any way. The best way to accomplish this is utilizing a 90-90-90 position while eating.

- Use a high chair or booster to provide support for a child that has difficulty.

- Maintaining an upright seated posture or postural stability to maintain their position.

- Seat variations may be needed for children that can’t seem to stop moving to provide input while keeping them at the table for mealtime.

- Wobble cushion

- Ball chair

- Active chair

- Vestibular input and strategies are helpful for both over and under-responsive kiddos. For those that are under-responsive, the activities can be more intense, last longer, and provide more input while approaching the same tasks in the opposite manner will benefit over-responsive children and help them build tolerance and understanding of their vestibular system.

Many of our kids move all over the place. They have a hard time sitting for mealtime and with self-feeding with utensils because of the coordination piece. We will talk about positioning in another slide, but it is important to increase hand-to-mouth coordination.

There are many different intervention strategies that we can use to help regulate the vestibular system. With 99% of the kids with ASD that I see for feeding, I provide vestibular and proprioceptive input before feeding, along with oral input. It helps to regulate their system. In general, most kids benefit from vestibular intervention to increase seated tolerance.

Sensory Systems: Proprioception

- Impact on Feeding

- Difficulty manipulating, grasping, and coordinating utensils and hands for self-feeding

- The pressure exerted by the jaw for chewing

- Knowing where food is in the mouth and how much can be tolerated

- (overstuffing is a sign of decreased proprioceptive response)

- Knowing where the tongue, lips, and cheeks are in relationship to the teeth so that they aren’t bitten during chewing

- Intervention strategies

- Under-Responsive

- Heavy work (activities for small spaces, indoor, different

- settings )

- Animal walks (free card game)

- Structured movement (trampoline, swing, slide, pushing, pulling, sports)

- Sensory Sock

- Weighted blankets

- Joint compressions

- Resistance crawl tunnel

- Over-Responsive

- Calming activities

- Desensitize and build tolerance for proprioceptive input

- Weighted tools (blankets, lap pad, vests, ankle or wrist weights, pencils) to build awareness of the body

- Deep pressure input

- Practice body awareness activities (imitating and identifying body)

- Simon says

- Yoga

- Under-Responsive

For proprioception, kids have a hard time grading their jaw movement for chewing. They may chew with an open mouth or chew very softly. Thus, it is tough for them to break down food, especially chicken nuggets, which are preferred by so many kids on the spectrum. Often, they do not close their teeth all the way. They disconnect between grading their jaw for pressure to chew a food harder or softer, depending on the texture. There is also a lot of overstuffing and pocketing because they do not know where the food is in their mouth. They do not understand that.

As noted above, there are many different strategies to work on the proprioceptive system, depending on their response to it.

Sensory Systems: Vision

- Impact on feeding

- Children may rely on visual cues for acceptance.

- Requiring the same box or packaging to accept an item

- Inspect food closely before trying

- Refusing just based on visual

- Overstimulated by visual of new or non-preferred food

- Intervention strategies

- Hypersensitive

- Repeated exposure (10-15 exposures before acceptance/trying is common)

- Keep providing the same food item over and over, in multiple ways (sliced tomato, chopped tomato, whole cherry tomato)

- Clean, simple eating space

- No visual distractions (TV, books, or toys)

- Low lighting may be beneficial.

- Simple plates and utensils, only a few colors

- Meals shouldn’t be visually overwhelming:

- Small portion sizes

- Single-ingredient items (don’t mix multiple foods like a casserole)

- Deconstruct recipes to make visually simpler

- Only provide a few food items (allow for more after consumption)

- Use only a few colors of foods on the plate

- Repeated exposure (10-15 exposures before acceptance/trying is common)

- Hyposensitive

- Bright colored and detailed utensils and plates

- Creative visual presentation

- Cookie cutters, food picks

- Visual charts for mealtime schedules, mealtime routine, and eating behaviors

- Present food that’s visually stimulating and engaging

- Multiple colors and textures

- Hypersensitive

This is probably one of my most favorite systems to talk about as it is essential. Often, we do not provide as much education on this system. The presentation of food is so important for kids on the spectrum. Often, they are immediately upset if they see it all because of visual presentation. We want to provide many suggestions for visual presentation. An example is noted below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Examples of food presentations.

The plate on the right is overwhelming for any human. With the example on the left, blueberries and strawberries are the preferred foods. That is why there are more of those options. We always want to have a preferred food on the plate because we want to engage the child. I never give a child all new foods or all non-preferred foods as there will be no engagement. I want to give them something that is preferred and familiar.

Then, I want to use strategies like food chaining, which we will talk about in another slide how to relate new food to familiar food. In the above example, red strawberries and round blueberries are the preferred foods. Now, I am going to give them a round red tomato. There is a better chance that the child will interact with that one tomato versus 10 as it is less overwhelming from a visual standpoint. It is also smooth and round and looks the same as some of the plate's preferred foods. The pretzels and the raw zucchini could also be preferred foods or something that the child has seen or tried before. The only new thing or the thing that we are working on is that one tomato.

Many goals in feeding therapy are too broad and ambitious. It is hard to work on feeding with a person who has rigid preferences and sensory discrepancies. We need to try to set them up for success. One way to positively influence this is by using the visual system. I have listed many interventions for that.

Food Chaining

- Food Chaining: The Proven 6-Step Plan to Stop Picky Eating, Solve Feeding Problems, and Expand Your Child's Diet

- Cheryl Fraker, RD, LD, CLC, Mark Fishbein, MD, Sibyl Cox, RD, LD, CLC, Laura Walbert, CCC-SLP

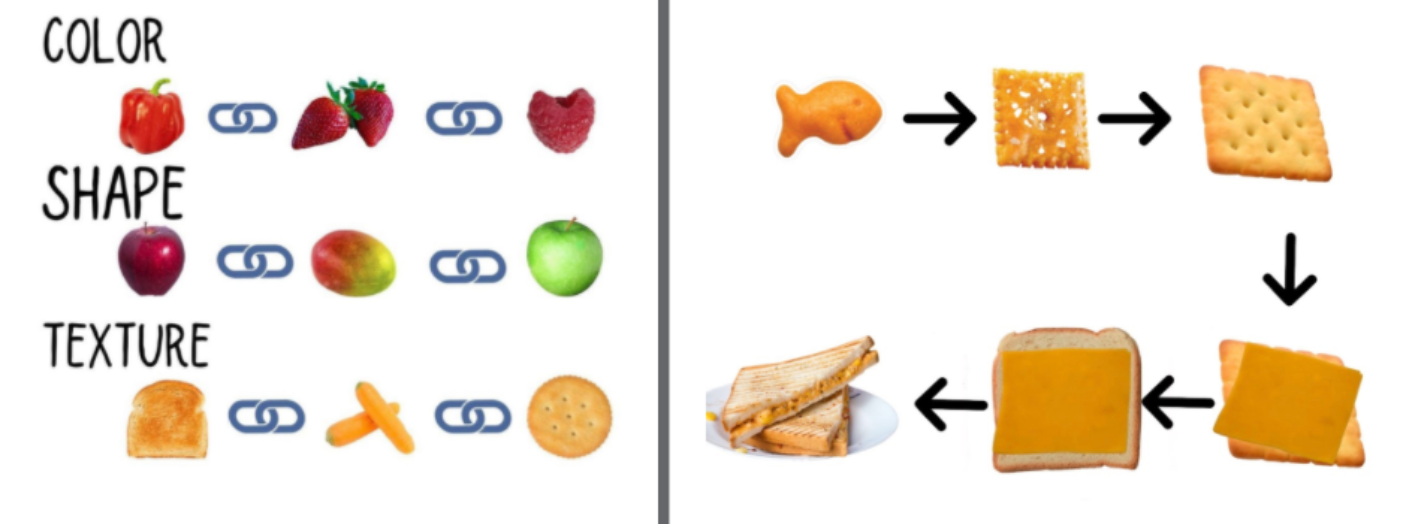

Food chaining is a broad topic. There are trainings and books on this topic. It is a gradual expansion of food based on food preferences using characteristics like color, size, and texture. Using this technique, you can expand on what the child is already eating. We want to model eating the food, but stop the habit of using words like "mmm," "yummy," "good," "bad," "eww," "yucky," et cetera. These descriptive words have no meaning, and they are extremely abstract. Instead, we want to give them concrete relationships. "This is my favorite Goldfish. You eat it all the time. It's orange, it's crunchy, and look, it crumbles." Then, "Here is a Cheez-It. It's also orange and crunchy. It crumbles in my hands. Let's see what happens when I put it in my mouth." I then would put each one in my mouth one at a time and talk about what it does. "It's crunchy. It's loud when I chew it. It's kind of salty. It moved around all over my mouth. It was easy to swallow." During the session, I would talk about all these things to have a concrete way to relate to this new food and chain it to their preferred food.

Color, shape, and texture are also impactful. For example, many kids will only eat orange or tan foods. We can figure out ways to get nutrition in based on color as well. With that being said, I prefer that they eat foods in multiple colors, but initially, we want to take those rigidities and use them for our benefit. If orange is what they are eating, then I will find every orange food on the planet to link to what they are already eating. Then, we can create multiple food chains off of that. Figure 2 shows some examples.

Figure 2. Examples of food chaining.

The food chain on the right is just a simple one I made. If Goldfish is the only orange crunchy cracker that a child eats, I can expand to Cheez-Its. Next, we can expand to a different shape. Now, we can move to orange cheese on a cracker and then a sandwich. We can then chain to a different color of cheese or shape like shredded. We could also have melted cheese. Try not to think about it as linear, but more like a chain and how you can go in different directions from those choices and successes.

Liquid Consumption/Cup Drinking

Let's now look at liquid consumption and cup drinking from a therapeutic standpoint. Figure 3 shows some examples of different styles of cups.

Figure 3. Different types of cups.

The two cups on the right are just small open cups. The EZPZ cup and medicine cup are my favorite to use because they are cheap, plastic, and do not break. When teaching open cup drinking, you should use a small amount of water. This is also ideal for young kids as well due to their small size. If you have an older child, you can use a more standard open cup because their hands are bigger. However, I would still use a small amount of water. The other issue with a cup's height is how much they have to tilt it to get in their mouth. Cup drinking can be limited by radial deviation of the wrist to tilt the cup and head motion. Young children on the spectrum, who use sippy cups or bottles for extended periods, often have limited neck extension. This is also going to impact their vestibular system. We need to help them work on this motion to learn how to drink out of the open cup.

Generically speaking, open cups and straw cups are the only types of cups that I want a child to have after transitioning from breast to bottle. Those should start being introduced at about six months of age. For toddlers that are ready, we can skip the sippy cup altogether with the two straw cups shown on the left. There is the Honey Bear cup and the one from ARK Therapeutic. I like this one as it has a tough silicone straw. With these, when a child closes their lips over the straw, and you squeeze it, liquid comes out of the straw. This is cause and effect. They start to understand that by closing their mouth on this, something comes out of it. Then, you can decrease the pressure, they will have to suck to get the water or liquid out of it. This is one way that we teach straw drinking. Another way is to capture liquid in a straw, plug it with your finger, and then drop it into the child's mouth to show cause and effect. This helps to connect the dots for them. We want a firm straw rather than one that collapses easily.

The 360 Cup has a silicone piece that prevents spillage. However, it causes an over-activation of the top lip and stress on the jaw from an oral motor standpoint. It causes poor oral motor skills. The magic trick is that you have to take the silicone piece off, and now it is a perfectly appropriate open drinking cup. It will spill, but this is how you can change that cup that so many families have and make it more appropriate from an oral motor standpoint.

Chewing, Utensil Use, and Self Feeding

As I said, many children with ASD have difficulty grading their chew. They can also have a very poor chew or are not chewing at all. They may suck, smush, or break down the food with their saliva. Figure 4 shows some feeding utensils.

Figure 4. Examples of feeding utensils.

Sometimes, we have to go back to the basics, like using pre-spoons (on the left). These have cutouts and ridges on the handle. It allows the child to scoop food onto that spoon, and then no matter how the child puts it in their mouth, they are going to get food. They do not have to have as much coordination as they do with a traditional spoon.

Self-feeding is important for oral motor skills because children need to have the utensils in their mouths, on their molars, on their cheeks, et cetera.

We also have to have reflexes, like tongue lateralization, to chew. When a child is fed by somebody else, all of that motion and food stays very central in their mouth, and they do not get any of that sensory exposure. Thus, I want every child to feed themselves, pretty much from the first time they eat food. Often, kids on the spectrum, even toddlers and older, are completely fed by someone. We want to change t